Books

Alternative Commemoration of Mao, Review of ‘Mao’s Great Famine’

In light of the 120th birthday commemoration last year for Mao Zedong, the Chinese Communist Party continues to elevate him to emperor-like status. Indeed, there are over 2,000 statues in Chinese cities commemorating the controversial leader. It might be pertinent for the government and the people of China to scrutinize the actions of the revered figure.

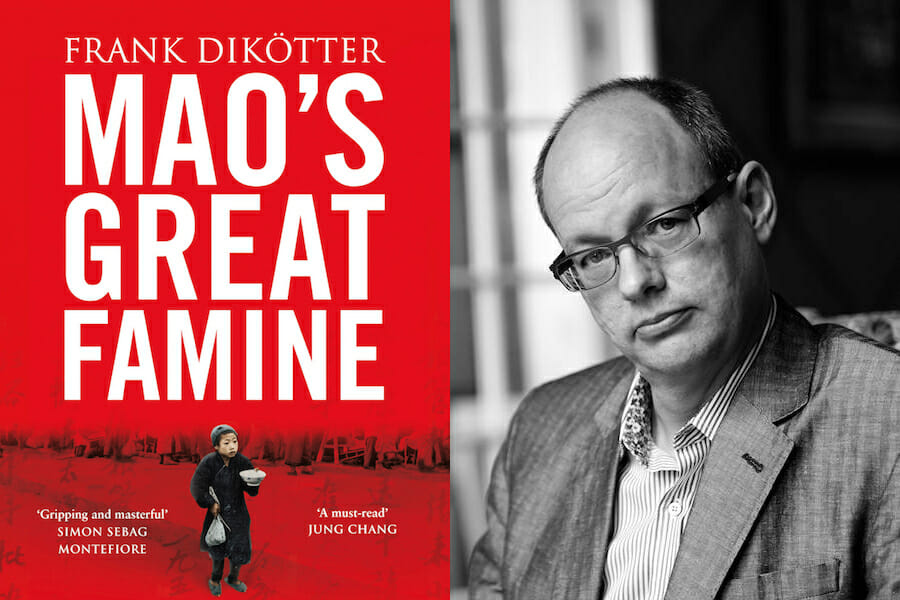

Since such scrutiny seems implausible in the one party state, the enlightening work of Frank Dikötter will have to suffice. Although not afforded access to sensitive documents, this has not stopped the Chair Professor of Humanities at the University of Hong Kong (only one of many prestigious accolades) on publishing several books on contemporary China like The Age of Openness: China before Mao (2007). Mao’s Great Famine (2010) must be considered his masterpiece because the work compiles a massive variety of statistics, records and other scholarly work on the Great Leap Forward.

Dikötter reasons that those killed between 1958 and 1962 are close to 45 million people through agrarian collectivisation (compared with a range of 15-35 million from previous researchers).

The book is structured into six parts and it seems there is no coincidence that the book is clearly divided into two distinct sections.

The first section (comprising parts one and two) focuses on the party’s relationship with its own people and with the outside world. It describes how the party has operated in the past and gives readers an insight into the bureaucratic functions at work and how a heavily idealised figure can blind the party and population to the realities on the ground.

Understanding party politics and the bonds it formed with its people is crucial in order for the reader to understand the implications of Mao’s efforts to collectivise and the party efforts to realise his dream. Often crimes were perpetrated by the lower echelons of the party, described as Dikötter as ‘militia.’ This lack of challenge to the central authority, from either indoctrination or terror, accelerated the starvation across China.

Each part of the book interweaves party politics and the actual application of collectivisation. It is to Dikötter’s credit that his masterful use of language compliments the extensive levels of research. His essay on the sources at the close of the book is surely a modest testament to the comprehensive depth and breadth of his examination of the events, making it not only a tantalising, but also a reliable read.

The documentation relentlessly attacks the policies instigated by Mao, and charges are levied at the local cadres in charge of facilitating the carnage. So the only potential criticism of the book is the reluctance to criticise Mao’s decisions as merely an extension of his paranoid ego, Instead it condemns the party and its inability to present Mao with facts forcefully. The book explores the fear of disappointing the leader, but wilful ignorance does not seem to be sufficient absolution in favour of denouncing the likes of Zhou Enlai and Liu Shaoqi. Perhaps readers should become more informed on the effect of personality on politics. North Korea’s Kim Jong-Un is an often-cited example of the cult of personality. However this is a minor criticism of an otherwise exceptional work on the legacy of Mao’s China.