Books

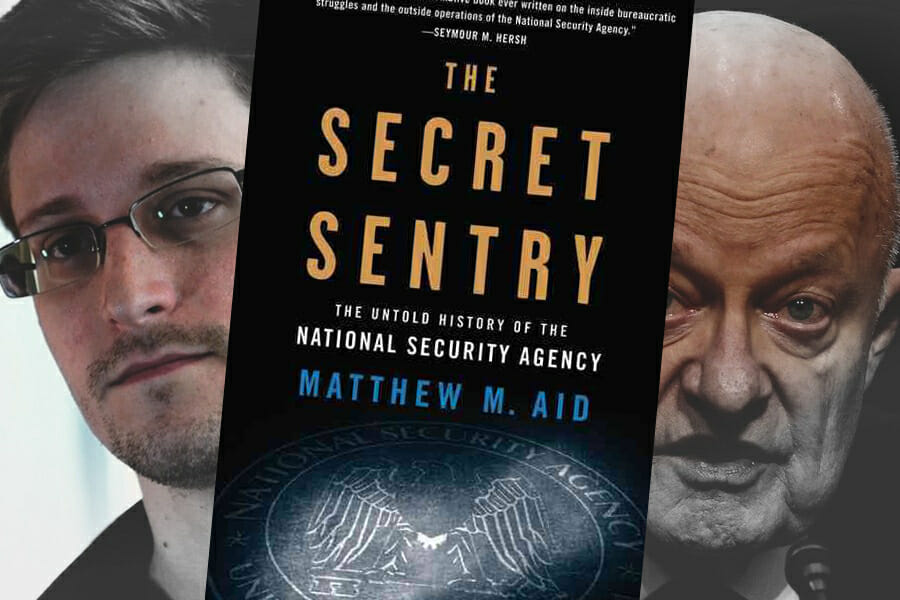

Review: ‘The Secret Sentry’

Thanks in part to US fugitive, Edward J. Snowden, the National Security Agency (NSA) is again in the spotlight. According to the former US intelligence contractor, not only is the NSA eavesdropping on foreign telecommunications, it is also monitoring the electronic communications of Americans. Like Jihadists, foreign leaders, international aid organizations, multi-national corporations and even ordinary citizens are allegedly monitored by America’s leading signals intelligence agency. Needless to say, Snowden has brought much unwanted attention on the secretive NSA. Besides complicating the spy agency’s work by revealing sensitive espionage methods, Snowden’s revelations also forced the Obama administration to introduce measures ending NSA surveillance of close US allies. This is of course not the first time the NSA found itself in the limelight.

The first time the NSA ever came under intense public scrutiny was in the mid-1970s when it was investigated by the Church Committee for alleged abuses. Thanks to that public hearing, many Americans came to learn for the first time that the country had a spy agency called the NSA. Then in 2005, the New York Times again called attention to the NSA by revealing that the spy agency was monitoring the electronic communications of hundreds of Americans as part of the US War on Terror. That exposé too created a firestorm not least because the NSA was engaged in warrantless domestic surveillance possibly in violation of US laws. Now almost a decade later, thanks to Snowden, the NSA is again in the spotlight for the wrong reasons.

But what is the NSA actually like? Is Snowden’s depiction of the NSA accurate? Is it as almighty as portrayed? These are all important questions with major implications for national security and civil liberty.

Published by Bloomsbury Press in 2009, The Secret Sentry is a significant piece of work on the NSA. Chapter by chapter, Matthew Aid lifts the thick veil of secrecy to give the reader a rare peek into the inner workings of this ultra-secretive spy agency.

Tracing the troubled beginnings of the NSA in the 1940s to its central role in Afghanistan today, Aid provides a detailed historical account of the evolution of the NSA in the last 60 years. Indeed, one might be surprised to learn of the NSA’s humble beginnings considering its massive size and technical sophistication today. Drawing extensively from declassified documents and interviews, the author carefully maps out how a tiny communication intelligence service – made up of a few skeleton crews in the aftermath of World War II – transformed into the mammoth spy agency that the NSA is today.

Created in 1952 by President Truman, the NSA is today one of the largest and most advanced spy agencies in the world. According to Aid, the NSA was already capable of vacuuming up roughly 80 terabytes of electronic data a day in 1995. By comparison, the entire printed collection of U.S. Library of Congress amounts to only about 10 terabytes. With an estimated US$10 billion annual budget and a workforce of 60 thousand civilians and military personnel, the NSA is one of the largest intelligence services in the world today. Working with other US allies, the NSA has managed to blanket the entire globe with an electronic surveillance dragnet. From primitive short-wave radio transmission to global satellite communication to high-tech fibre optic telecommunication, the NSA listens in on the entire spectrum and few electronic communications – text messages, faxes, emails and phone calls – and apparently escapes interception.

However, this transformation of the NSA into what it is today has not been an even one. One notes that in addition to protecting the US from external enemies, the NSA also had to constantly guard its turf against other US intelligence agencies and departments eager for a slice of the US signals intelligence program. By detailing those bureaucratic feuds and jurisdictional squabbles that plagued the NSA over the years, Aid presents an organization that is constantly working to stay relevant. As of 2009, it is evident that the NSA remains beset by a whole host of problems that continue to limit its ability to protect the country. Clearly, this is not a spy agency that is as almighty as it is thought to be.

Meanwhile, for those with a keen interest in more recent events, The Secret Sentry also zooms in on the US intelligence war in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. From the caves of Afghanistan to the cities of Iraq, the author provides a detailed account of the secret war that is being waged by the NSA against America’s worst enemies. If anything, The Secret Sentry is so rich in this aspect that it will undoubtedly be studied by US adversaries around the world.

Still, one might ask how The Secret Sentry distinguishes itself from the NSA’s own internal account of its history. Those who examine NSA documents declassified under the Freedom of Information Act know that there are always informational gaps in those materials due to omissions or redactions. Filling in those informational gaps is extremely difficult often because they pertain to activities that are still sensitive. In The Secret Sentry, Aid carefully incorporates information that he has obtained through exclusive interviews with key intelligence personnel both past and present. By doing so, the author effectively closes out many such informational gaps. The end product is a well-researched book that is rich in details and highly informative.

In terms of shortcomings, The Secret Sentry is definitely not a ‘fun’ read so the reader may be disappointed if he or she is looking for something sensational. Nevertheless, one should also note that it may well be the author’s intention to deliver a balanced and formal historical account. Indeed, one may even see The Secret Sentry as an academic piece of work since it refrains from anything speculative or biased. Another shortcoming is that the author brings up but failed to elaborate on a number of rather critical issues. As a case in point, he raises throughout the book the enduring problem of ‘turf battles’ between the NSA and other US intelligence agencies but leaves out how that issue might be resolved. This shortfall certainly leaves the reader wondering if the US intelligence community is doomed to repeat the same mistakes that resulted in 9/11.

So how does the picture of the NSA presented in The Secret Sentry measure up against that given by Snowden?

After reading The Secret Sentry, one will likely develop a somewhat different view of the NSA. The NSA will no longer appear to be almighty. Certainly, it appears to be a lumbering bureaucracy that needs to keep pace with not only the latest advances in computing and communication technology but also with wily adversaries from around the world. In addition, the NSA must also contend with other US intelligence agencies and departments to run the country’s signals intelligence program. One may even be surprised to learn that NSA relations with some of its international partners are actually better than those it shares with some US intelligence agencies. Lastly, one will come to realize that the NSA, for good or for bad, operates in an environment where privacy concerns can hamper its work and limit its ability to gather vital intelligence. Even though the NSA did become more aggressive in the aftermath of 9/11, it has always been unwilling to engage in domestic surveillance.

In all, The Secret Sentry helps us to understand and see the NSA for what it is, its purpose and place within the broader US intelligence structure. It is a well-researched book intended for those looking for an in-depth and balanced study of America’s leading signals intelligence agency.