Did the Senkakus Sink Sony?

I came over this measured exercise in opinion journalism penned by “Alec Ross, Senior Fellow at Columbia University’s School of International & Public Affairs” over at Huffington Post:

North Korea is a miserable, backward, hellhole of a place. It has a per capita GDP of less than $2,000 — trailing Yemen, Tajikistan and Chad — and about one-sixteenth the size of the GDP of South Korea. The Hermit Kingdom derives its power through the twin pillars of state repression and an all-encompassing propaganda apparatus.

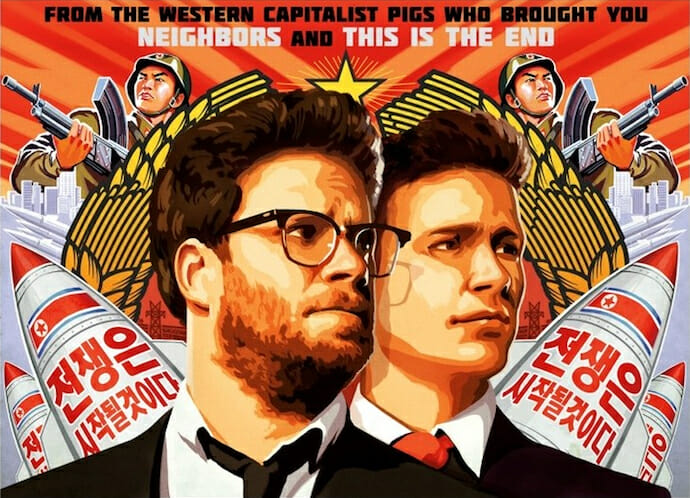

This poor, delusional country managed to wallop Sony after it objected to the content of some movie which I can’t remember the name of at the present moment but which looks boring and stupid…

Kinda funny, in a way, since the FBI has stated there isn’t sufficient evidence to attribute the attack to North Korea at the present time, and in fact some people are pointing fingers at the People’s Republic of China instead. More about China later.

Hmmm, I said to myself, and I surfed off to find out whether Mr. Ross was indeed a fellow at some hallowed Ivy, or perhaps the meth-crazed denizen of some non-accredited on-line institution in Columbia, South Carolina.

My concern evaporated as I perused Mr. Ross’s lovingly curated Wikipedia page, helpfully titled “Alec Ross (innovator)”:

Alec Ross (born November 30, 1971) was Senior Advisor for Innovation to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton for the duration of her term as Secretary of State, a role created for him that blends technology with diplomacy. As Secretary Clinton’s “tech guru,” Ross led State Department’s efforts to find practical technology solutions for some of the globe’s most vexing problems on health care, poverty, human rights and ethnic conflicts, earning him numerous accolades including the Distinguished Honor Award. In 2010 Ross was named one of 40 leaders under 40 years old in International Development, and Huffington Post included him in their list of 2010 Game Changers as one of 10 “game changers” in politics. He is also one of Politico’s 50 Politicos to Watch as one of “Five people who are bringing transformative change to the government.”

Foreign Policy magazine named Ross a Top Global Thinker in 2011. U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Samantha Power, speaking at the White House referred to Alec Ross as “One of the most creative people probably that the U.S. government has ever known.” Profiled in 2011, Time Magazine describes how Ross is incorporating digital platforms into the daily lives of U.S. diplomats and his support of programs to train activists in the Middle East. Time Magazine also named Alec Ross one of the best Twitter feeds of 2012. In 2012, Newsweek named Alec to their Digital Power Index Top 100 influencers, listing him among other “public servants defining digital regulatory boundaries,” and the TriBeCa Film Festival awarded Ross a Disruptive Innovation Award. Alec Ross is recipient of the Oxford Internet Institute OII Award 2013.

Gadzooks, I thought. Benghazi! No, really, I realized this is Hillary Clinton’s go-to guy for evil-empire related digital policy, besties with Samantha Power, and also an indispensable, foundational figure in the compilation of end-year listicles.

Upon reviewing these credentials, my concerns were allayed, and I look forward to our 21st-century high speed, high efficiency digital justice system, which pitches cumbersome anachronisms such as evidence and due process off the steamship of modernity (to paraphrase my favorite Mayakovsky bit), and allows the simultaneous posting of crime, sentence, and punishment on the pages of our new court record, Huffpo.

But seriously.

The Sony hack apparently involves a major investment of time and resources, which are available both to governments and to criminal gangs. What makes the Sony hack kinda special is that, once access was obtained and the goodies extracted, the intruders torched the place and made a public spectacle of their crime.

Going the extra mile in vandalism and humiliation would seem to argue some political purpose beyond simple malice, mischief, and greed, and observers have naturally gravitated toward a narrative of North Korean revenge for The Interview.

But, you know, maybe something Chinese. Not an operation sanctioned by the PRC government, to be sure—the benefits are miniscule (unless Xi Jinping just absolutely had to see Annie pre-release) compared to the potentially immense diplomatic and economic costs—but maybe some kind of off the books operation by rogue, nationalistic minded hackers who decided to stick it to a vulnerable Japanese corporation as punishment for the Japanese government’s confrontational attitude toward the PRC over the Senkakus, the pivot, etc.

One of the more interesting cases bubbling along in cybercrime is the early-December arrest of 77 (!) PRC nationals crammed into a house with their computer gear in an upscale Nairobi neighborhood, allegedly with criminal designs on the Kenyan banking system.

The PRC surfs and hacks the world looking for system vulnerabilities, and I’m beguiled by the possibility that a government cyber operation discovered a vulnerability in the Kenyan banking system, and a freelancing group of hackers decided to exploit that information for some private and profitable breaking and entering.

I suspect in the brave, new world of PRC hacking, there is a growing cadre of entrepreneurially minded or ideologically driven hackers who can bring impressive information, resources, and skills to bear on a chosen objective.

Given the difficulties of identifying a smoking gun as to an originating server—let alone a controlling individual or institution—Ross speculated a private sector riposte which sounds rather ridiculous: “It is only a matter of time before some hotshot group of engineers recognizes and stalls a cyber attack and instead of calling the authorities (who can’t do anything anyway), the VP of Engineering orders a counter attack against the aggressor. If Sony had a better engineering department — if it were a little more Northern California instead of Southern California — I wonder what would have happened if they had identified the source of the hack and shot back with a DDoS attack. Would the North Koreans have considered this an ‘invasion’ by the United States or Japan (where Sony is actually headquartered). They are complete lunatics, so they probably would.”

I can only hope that, if Hillary Clinton is elected president, they will give Alec Ross a phone that can only call 911 and a computer that is not plugged into the Internet.

Functionally, the Sony hack resembles the “Shamoon” hack of the Aramco network in Saudi Arabia, itself perhaps retaliation for the US/Israeli Stuxnet attack on Iran’s centrifuge operation. In addition to a data drain, Shamoon featured the wiping of target hard drives and the presentation of a taunting message on computer screens.

I wrote about Shamoon for Asia Times Online in 2013, and pointed out the implications of larger and more sophisticated cyberintrustions. “The PRC and Russia have lined up behind a proposed ‘International Code of Conduct for Internet Security,’ an 11-point program that says eminently reasonable things like: Not to use ICTs including networks to carry out hostile activities or acts of aggression and pose threats to international peace and security. Not to proliferate information weapons and related technologies.”

It is, unfortunately, a simple and incontrovertible fact that, if we want to effectively detect, block, and investigate cyberattacks, the solution is tightly monitored, internally accountable national internets along the lines implemented by the PRC, Iran, and, increasingly Russia and Brazil. Under this model, states have the capability, right, and responsibility to police their digital borders as they do their physical borders.

This approach is, of course, anathema to Mr. Ross, as it raises the specter of oppressive governments stifling dissent and inhibiting free expression at the same time they pursue cybersaboteurs.

It also flies in the face of the US strategic and economic interest in an open transnational network accessible to Google bots and NSA penetration, that places American government and corporate entities at the profitable, vulnerable heart of the Internet, and makes it dependent on US good offices, just as the international financial system still is today.

Unfortunately, the US, in its interest in sustaining an open, transnational, and easily compromised Internet, is at the same time demonstrably unable and unwilling to effectively secure it or police it fairly. That’s why the current Internet has the structural robustness and integrity of a bag of shit thrown from a third-story window.

And that’s why I’m afraid our response to outrages like the Sony hack will be to use the language of deterrence and intimidation–and private sector vigilantism–to shift focus away from the profound and probably irreconcilable contradictions that form the foundation of the current Internet.