Turkey’s Taksim Square is not Tahrir

No one predicted that the demonstration in Istanbul’s Gezi Park a week ago would morph from a peaceful demonstration against the government-backed plan to make way for a commercial development into a spirited nationwide challenge to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). Some have called the protests Turkey’s version of the Arab Spring, but that does not appear to be the case. While half the country did not vote for Mr. Erdoğan and the AKP, and many object to what they see as the gradual “Islamization” of Turkish society and an increasingly authoritarian manner of governing, Mr. Erdoğan has established an impressive political franchise that many would also argue has resulted in a variety of net benefits for the country and its people.

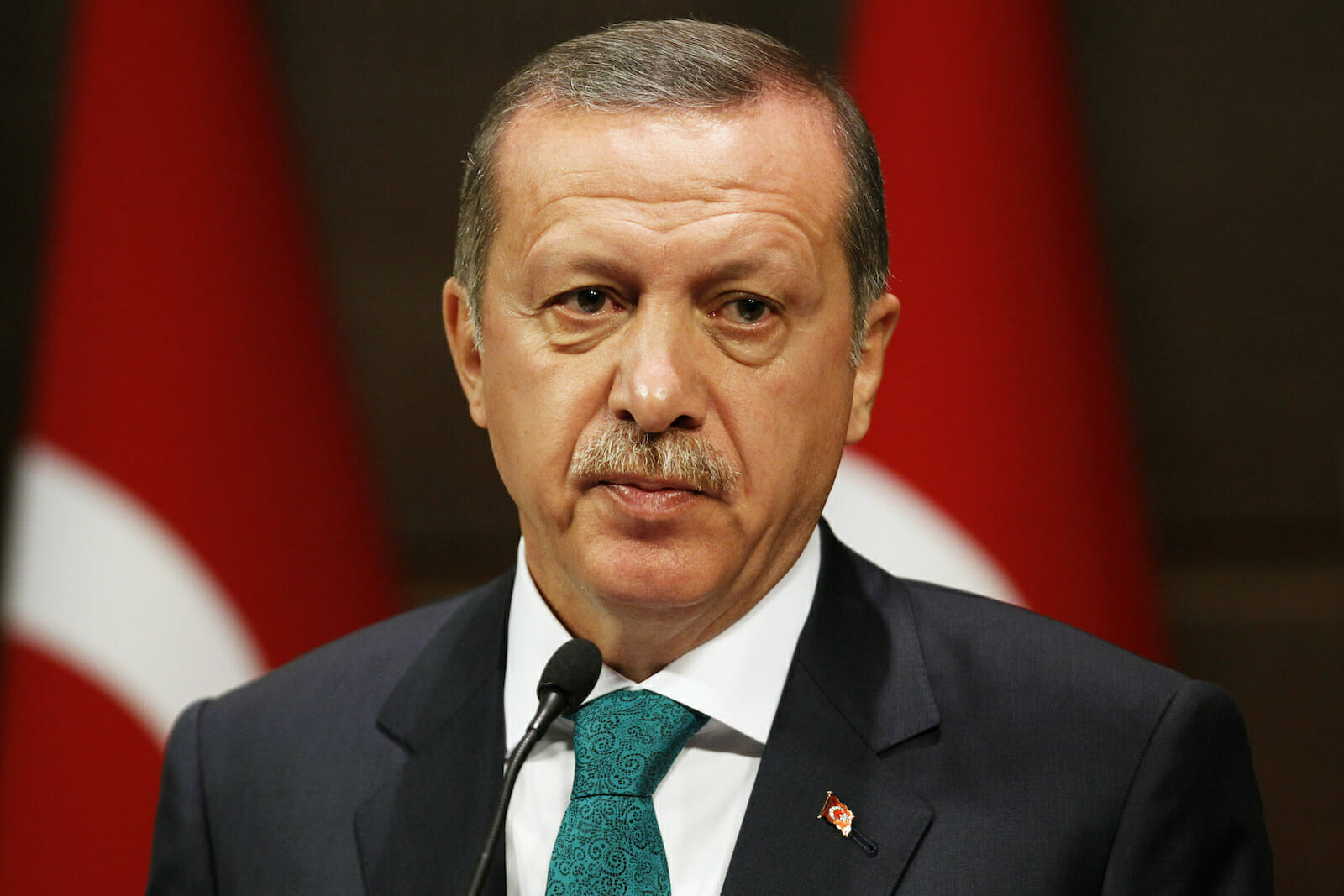

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has remained defiant in the face of accusations of authoritarianism and calls for his resignation. He has patronized the demonstrators on several occasions, dismissing them as an extremist fringe of looters and thugs set out by the political opposition to provoke the Turkish people with misinformation. Mr. Erdoğan is confident his grip on power will be maintained, and that his core base of supporters — mostly rural religious conservatives — will blame what they consider to be secular protesters for stirring up trouble.

The protesters represent a wide swath of ages, ideologies, religions, and socioeconomic classes united by a common opposition to Mr. Erdoğan, who they view as a dictatorial threat to the country’s secular democratic institutions.

When Mr. Erdoğan’s government pushed through reforms to bring the country in line with European Union standards a decade ago, many voters among these smaller constituencies supported him because the reforms brought economic prosperity and greater liberal freedoms.

But Mr. Erdoğan’s gradual slide toward authoritarianism has reinforced a sense of marginalization among non-AKP segments of the population, who now see the government’s agenda and style as an extension of the AKP’s conservative supporters.

Over the last decade, the opposition to the AKP has remained weak and divided, mostly due to the failure of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) (the largest opposition party) to expand its appeal to voters outside of the country’s western coast. The CHP is now scrambling to become relevant within the context of the protests, but it seems unlikely to become a political force to coalesce the grievances of secular Turks into a cohesive movement to challenge the AKP.

In spite of recent events, the AKP retains a solid hold on power and Mr. Erdoğan remains the most popular prime minister in modern history. Under his leadership the government has made a bold attempt to end the Kurdish insurgency, the economy has experienced rapid GDP growth (tripling per-capita income), and he has generally reinforced Turkey’s profile as a regional power broker. It is important to remember that amidst the accusations that he is a dictator, Mr. Erdoğan was elected three times through free and fair elections — each time with a larger percentage of the vote. Moreover, if elections were held today, he and his AKP would undoubtedly win, as most Turks would agree their lives are better, the economy is stronger, and the country is better off with Mr. Erdoğan, than without him.

The protests are certainly a wake-up call for Mr. Erdoğan, particularly vis-à-vis marginalized liberal and secular voters. The protests will likely constrain his efforts to establish a new constitution that grants sweeping powers to the President — a position he was expected to pursue in next year’s election. But perhaps the most important legacy of these protests will be what they represent: a maturing democracy that has shed its dependence on the army to maintain order and political transition. Ironically, the protests would have been much more difficult without the political reforms Mr. Erdoğan pushed through early in his tenure. Turkish citizens have never felt more empowered to influence the actions and policies of their government.

In order for a collective net positive to result from the demonstrations in Taksim Square, the AKP needs to learn the art of compromise. While the government will likely take a series of small steps to pacify the protestors, it will probably not do much to address the fundamental dynamics that lay at the heart of the unrest. For this reason, more demonstrations are likely to erupt in the future. However, since most Turks do not view Mr. Erdoğan or his government as illegitimate, a Turkish Spring is not in the making. This is not Tahrir Square.