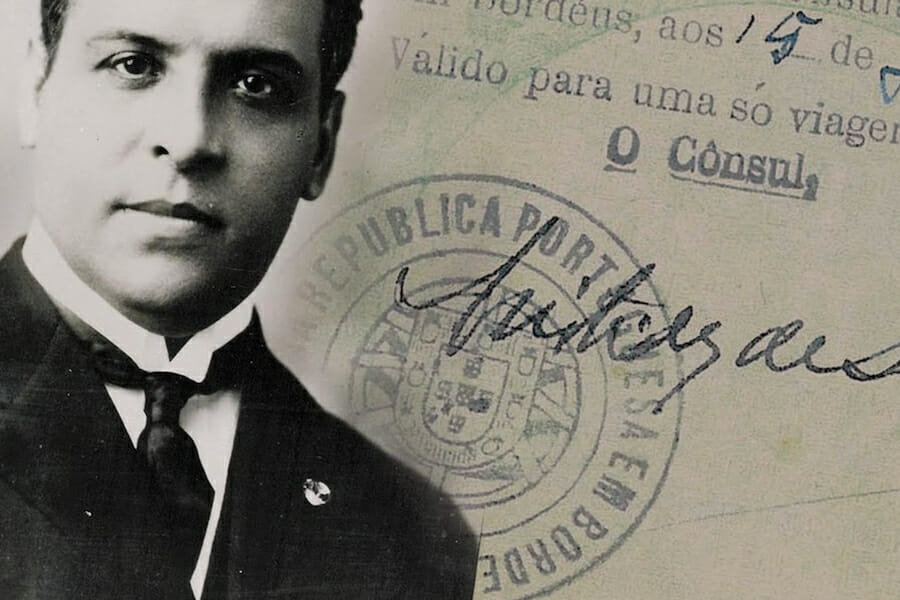

A Savior Remembered: The Life of Aristides de Sousa Mendes

“I would rather stand with God against Man than with Man against God.”

That is is how Aristides de Sousa Mendes, the then Portuguese Consul in Bordeaux, France is said to have responded to “Circular 14” – an order from the Portuguese Foreign Ministry headed by President Antonio Salazar. The order banned Portuguese diplomatic missions from issuing visas to persons of disputed or contested nationality, stateless persons and other Nansen passport holders. For many, mostly Jews who could not return to the country of their birth, this would have meant persecution and for some even death.

Sousa Mendes would defy these orders and by doing so, save thousands of lives. His own, however, would be hounded by an infuriated Salazar led government. Aristides de Sousa Mendes was born to an aristocratic family on July 19, 1885, in Cabanas de Viriato in the Centro Region of Portugal. He studied law in the Centro’s Region’s capital, Coimbra, and obtained his degree in 1908. Sousa Mendes married Maria Angeline de Sousa, who he had known since childhood and the couple had 14 children.

A fairly successful yet troubled diplomatic career followed with postings in Zanzibar, Brazil, the United States, and Spain. He often clashed with Foreign Office authorities and disciplinary proceedings were initiated against him on more than one occasion. After the establishment of the Ditadura Nacional, following the 1926 coup d’état led by General Manuel de Oliveira Gomes da Costa, Sousa Mendes was initially sympathetic towards and aided the regime’s aspirations as a representative of its diplomatic corps.

As the Second World War continued to create more refugees, more nations including Portugal started reacting unfavorably to accommodating them. Portugal was officially neutral, but unofficially Salazar’s Fascist regime was supportive of the Third Reich. For many refugees, particularly Jews in France, Portugal was also a strategic location from where they could safely sail to the United States of America. With the German invasion of Belgium and The Netherlands, the Government of Portugal issued orders prohibiting their entry to the country.

Sousa Mendes, a devout Christian, disagreed with the Foreign Office’s policies, stating that it was against both the Portuguese Constitution and the nation’s traditional and historical principles and decided to act according to the “dictates of his conscience” and started issuing visas to and in some cases even forging Portuguese passports at great personal risk to the thousands of refugees who had assembled outside the consulate. He arranged for free visas for many who could not afford the costs. His actions were further influenced by stories of Nazi’s atrocities that he had heard from his twin brother, a fellow diplomat stationed in Poland.

In June 1940, Sousa Mendes set up a production line and worked into the night, issuing hundreds, if not thousands of visas. He soon rushed to the Portuguese consulate in Bayonne and started personally supervising the issuance of visas to the refugees there, stamping them himself and writing requests to the Spanish government to allow free passage to the visa holders.

By now, information and rumors had reached Lisbon and Sousa Mendes was summoned to the Capital. The Foreign Office further telephoned border stations and ordered them to prevent the entry of anyone who held visas with Sousa Mendes’s signature. When informed of this, Sousa Mendes personally led the refugees along with his diplomatic escort to a border station with no telephones and helped them enter Portugal. In Portugal, Sousa Mendes was charged with issuing visas without permission, abandoning his position in Bordeaux, among other charges and was discharged from the service, stripped of his titles and blacklisted. This prevented him and his children from being able to obtain any sort of meaningful employment within the country.

In a memorable response during the disciplinary hearing, he stated that his “aim was indeed to save all those people who had suffered indescribably” and that “many were Jews, who were already persecuted and were looking to escape further persecution.” He further stated that “he could not differentiate between nationalities” as he was obeying the “dictates of humanity, that distinguish neither between race nor nationality” and recollected an instance when he was applauded by many people while leaving Bayonne. “Through me,” it was Portugal that was being “honoured,” he continued. For the rest of his life, Sousa Mendes suffered from poor health and died destitute on April 3, 1954.

Family members, who had immigrated to the United States and others who had been saved by Sousa Mendes’s visas soon began to campaign to have his actions recognized and popularized. In 1966, Israel’s Yad Vashem memorial to the Holocaust recognized Aristides de Sousa Mendes as one of the ‘Righteous among the Nations.” After the Carnation Revolution in Portugal, which peacefully overthrew the dictatorship, establishing a democratic state, Sousa Mendes’s story started resurfacing along with calls to honor his actions increasing.

In 1988, the Portuguese Parliament dismissed all charges against him, restored him to the diplomatic corps and honored him with a standing ovation. He had been awarded the Portuguese Order of Liberty a year earlier. Recognition, acknowledgment, and remembrance of Sousa Mendes’s life continued in many nations. In 1995, Portugal conducted week-long homage to Sousa Mendes’s life and his house was repurchased with government funds and gifted to his family for the creation of a foundation in his name.

The exact number of people to whom visas were issued by Sousa Mendes is hard to determine and along with many other aspects of his life continues to be a matter of historical debate. The last wish of Aristides de Sousa Mendes reportedly was to have his name restored within his nation. Years later, Mario Soares, then the President of Portugal would call him “Portugal’s greatest hero of the twentieth century.”