Rwanda and Reflection – 20 Years after Genocide

“I know there is a God because in Rwanda I shook hands with the devil. I have seen him, I have smelled him and I have touched him. I know the devil exists and therefore I know there is a God.” – Roméo Dallaire, Shake Hands With The Devil

In a time when civil strife is becoming ever more common, with examples of sectarianism in Syria, South Sudan and the Central African Republic; it seems pertinent that the UN Deputy Secretary-General Jan Eliasson made an address to participants at a memorial event at the UN Headquarters in New York on the 20th anniversary of the Rwandan Genocide. Eliasson said that “When people are killed or violated in the name of religion, race or ethnicity, everybody’s humanity is diminished.” To reflect on such atrocities, in which the population of Rwanda was literally decimated, may help contemporary politicians avoid similar catastrophes when religious and cultural groups are being slaughtered.

In 1993 President Habyarimana of Rwanda was forced to sign a power-sharing agreement with the Rwandan Patriotic Front (a Tutsi-led multi-ethnic force that began a coup in 1990), this allowed equal access for both ethnicities to participate in the political process in Rwanda. This could have been the time of redemption for a previously divided state, plagued by inter-ethnic violence for half a century. However, as history tells us this did not happen.

On the 6th of April 1994, President Habyarimana was killed when his plane was shot down over Kigali and the Hutu extremists, desperate to maintain the status quo, had their fall guy. The horror that was about to take place was led by Prime Minister Jean Kambanda, who shortly after being sworn in called for a genocidal rampage of the formerly ostracized Tutsi minority.

Further complicating the events of the massacre can be seen in a compilation of data of Rwandan society at the time, undertaken by the African Studies Centre at the University of Pennsylvania, and a fairly simple conclusion can be drawn; that there are very few distinctions between the two ethnicities. The cultural similarities include a common language (Kinyarwanda) and what can in other ethnic conflicts be a great divide, religion (such as Northern Ireland or Bosnia), 65% of the population are catholic often mixed with indigenous beliefs. The only division appears to be one of the socio-economic connotations with the ethnic distinctions, Hutu meaning servant and Tutsi meaning one rich in cattle. This pre-colonial division was entrenched by the colonial administration of Belgium who introduced identity cards for the different ethnic groups and proceeded to favor the Tutsi minority as a ruling class. These identity cards failed to disappear after decolonization and arguably did much to facilitate the speed with which the genocide was carried out.

Perhaps it was this early establishment of the superiority of Tutsis that created another dimension of bitterness, not only confined to ethnic and socio-economic differences, it associated the Tutsis as an arm of colonial domination. This debatably induced a feeling in the Hutus to perceive the Tutsis, who came to Rwanda in the 1300s, as somehow a foreign and hostile incursion, within the Hutu dominated society.

The genocide itself was seemingly a culmination of pre-colonial ethnic distinction, colonial administration, and the post-colonial chaos. In particular, the ability of the Hutu-extremist regime to capitalize on all of these elements only served to expedite the entire massacre. The murder was often committed with a simple machete used for clearance of fields, and the militias proceeded to use rape as a weapon of war, and the patrilineal nature of Rwandan society created years of social unrest for those born out of such attacks. It is estimated that 800,000 people were killed, a majority of whom were Tutsi but also Hutu moderates who resisted the extremist call to murder. It is a cause for great concern that the international community failed to respond in any meaningful way until it was far too late.

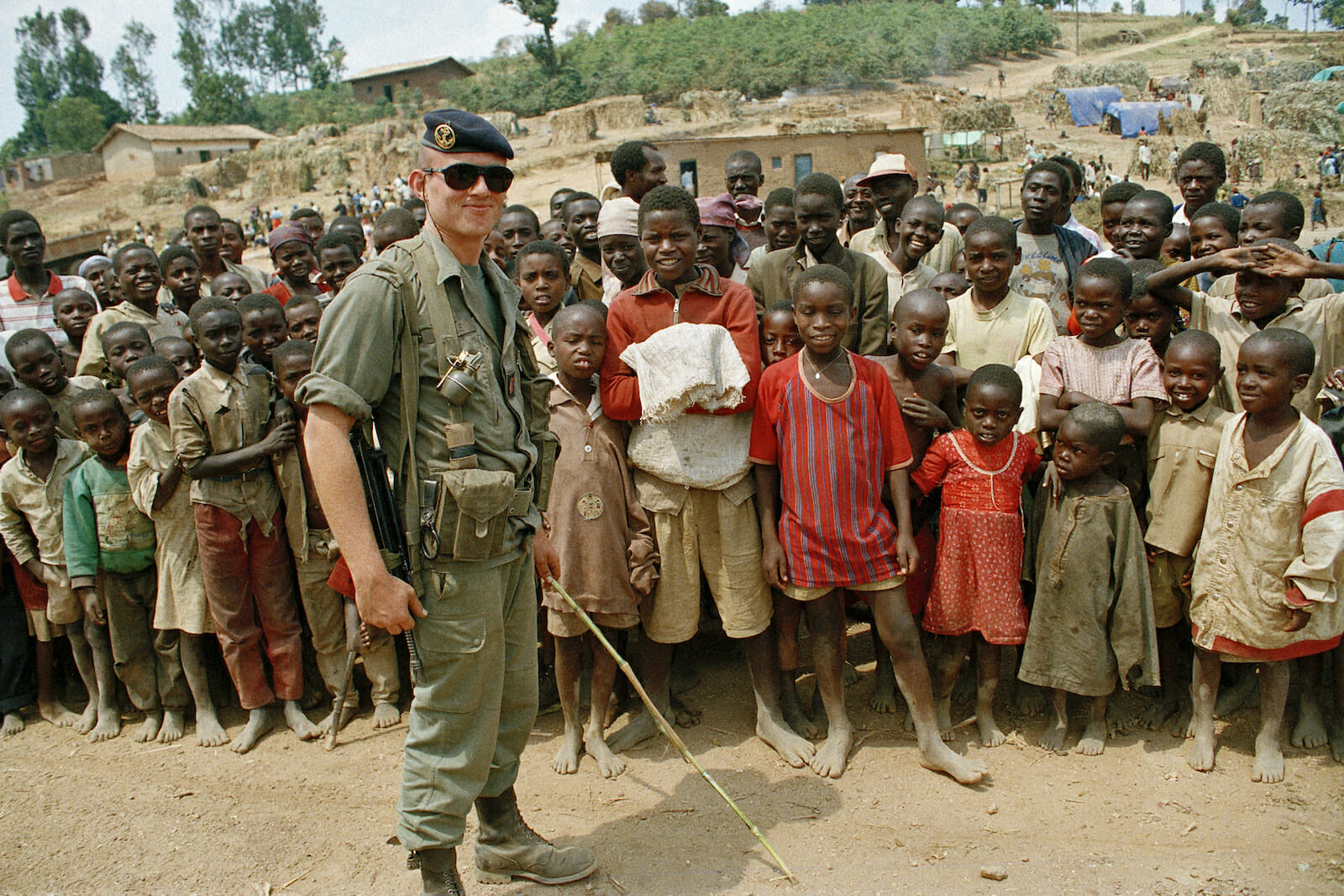

In the UN Declaration of Human Rights, created in 1948, article 2 stipulates that “Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race…” Such a bold statement is perhaps an overstretch when it comes to reality, but the most heinous crime of bodies like the UN, the US, and other major powers was their failure to even condemn or bring attention to the atrocities. The international community appeared to have abandoned a people in need, without any protection there was slaughter on such a massive scale that it set the entire region ablaze. Indeed not only content to standby and stay silent, but the UN Security Council also proceeded to vote on the withdrawal of the UN peacekeeping forces from 2,500 troops to 270. There are several explanations on why major powers refused to become involved. Conceivably the US wished to remain apathetic due to the events in Somalia in 1991, in which the American public became apprehensive of sending its troops to seemingly inconsequential areas around the world.

Sadly it seems that looking at Rwanda’s history, in particular, shows us that the cycle of ethnic conflict, makes such violence entirely plausible to return. On the world stage, the cycle of ignoring the plight of others appears no more evident than in Syria where an estimated 6.5 million are displaced inside its borders and 2.3 million are refugees; with over 100,000 have been killed, according to the UN. The problem remains as to whether the international community will heed the call of Jan Eliasson, “We can best meet this responsibility when we in the United Nations system realize the potential of our combined mandates and roles and when we operate as ‘one.’”