Dissent in the Ranks: Patronage and Politics within China’s Communist Party

As tensions continue to rise between China and her neighbours, it becomes increasingly important for the international community to understand the processes by which China’s leaders make decisions. The ruling Party is notoriously secretive about its inner workings, and though internal debate and discussion undoubtedly take place, the final result is always presented by a unified front.

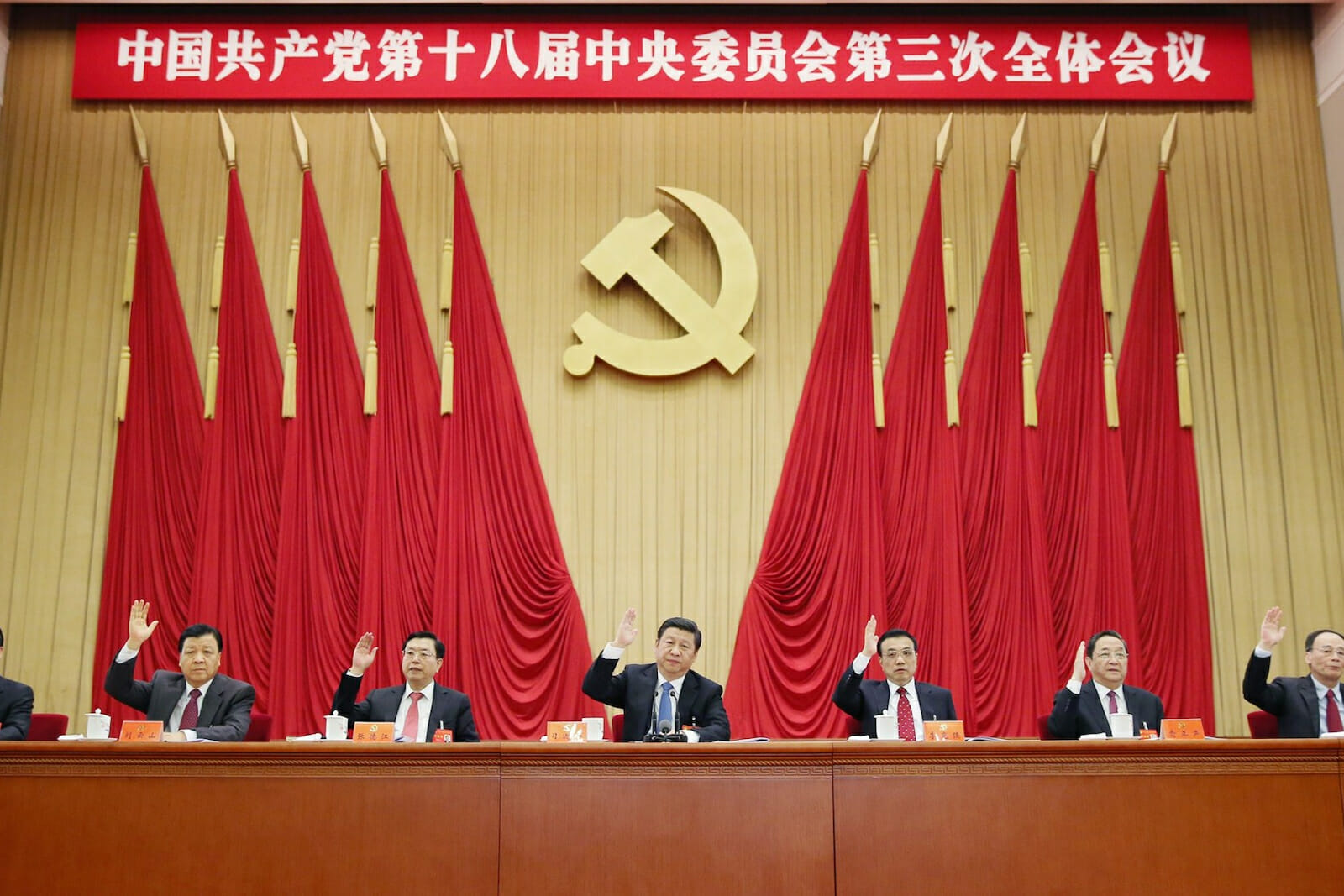

International scholars have long attempted to identify the various camps within the Party and the consensus is that there are at least two rival factions guiding policy decisions – the Shanghai bang, lead by Third Generation General Secretary Jiang Zemin, and the Youth League faction, lead by the Fourth Generation’s Hu Jintao. Analyses of the current Politburo Standing Committee, the inner core of Party leadership, identifies current General Secretary Xi Jinping, Zhang Dejiang, Yu Zhengshen, Wang Qishan and Zhang Gaoli as members of Jiang’s Shangai faction, while Premier Li Keqiang and Liu Yunshan are the now-outnumbered Youth Leaguers. On top of these two, analysts have also variously identified factions associated with the New Left movement, Tsinghua University, “Princelings” (the children of former Party leaders and Long Marchers), and the powerful People’s Liberation Army. This factional approach can serve useful for keeping track of who is “in” or “out” politically.

The composition of the current Standing Committee, for example, seems to indicate that Jiang Zemin has a far firmer grasp of power than his successor Hu and it masks the true mechanics of the Party’s internal politics in favour of a more clear-cut model.

If we take the factional approach too literally we ascribe certain political convictions to members of that faction, as we would in Western-style political parties. We begin to imagine that all members of Hu’s faction must share some common ideals that draw them together, and that by analysing the policies implemented by these faction’s leaders when they were in power we can predict those of their juniors, should they be given power.

However, the factions we perceive within Party politics are not based on shared political outlook but rather on the patron-client relationships known as guanxi. These are not dissimilar to the patronage networks seen in Elizabethan England, in which bureaucratic positions were used both to enhance one’s status and to confer favours upon underlings who could be relied on to support the patron in times of need. Clients could use the privileges bestowed upon them by their patrons to pass on favours to their own clients in turn, creating great networks devolving downwards from the original patron’s position.

One popular anecdote of patronage in Elizabeth’s time recalls a time when two rival lords entered London to attend Parliament, each riding with their entire extended patronage networks wearing their own colours to try to establish their superiority. Very few of the individuals riding in each column would have known the lord they followed personally, or likely even cared about the rivalry, but each would have been called to ride by their own patron to whom they owed their position.

This scenario applies to modern China. We may see a column ride into town wearing all one colour and identify it as a cohesive political faction, but in reality, each individual Party member is behaving so because of the obligation he feels towards his own respective patrons. Members of the Youth League faction do not necessarily share Hu’s own political views, but they are all members of an extended network of patrons and clients that stems back to Hu’s days in the Youth League, when he appointed his first clients to positions beneath him. Likewise, Jiang used his position as leader of the Party in Shanghai to establish his own support base. Both Jiang and Hu were in turn clients of Deng Xiaoping, who elevated them to the General Secretariat in turn.

As Deng’s clients, owing to their position and privilege to his patronage, both Hu and Jiang were obligated to follow his direction, just as their own clients currently in the Politburo Standing Committee will look to them for guidance. However since Deng’s death, both Hu and Jiang have found themselves at the top of their own separate patronage networks, independent of any patron’s support, and so they can act freely to achieve their own policy goals. This is what has created the two dominant factions that we see in action today, and raises interesting questions as to what might happen once Jiang dies – will all of his most powerful clients, such as Xi, become independent in turn: Might this deepen the schisms within the Party, with a number of patronage networks replacing the currently unified Shanghai bang?

Two other factors complicate this further – the status of the Princelings and the New Left movement. The Princelings, sons of former Party leaders, have some status independent of their patronage. Some, like Xi Jinping, use this to attract powerful patrons and to accelerate their rise through the hierarchy, but others might use this to create patronage networks not devolved from Deng through Jiang or Hu, allowing them to go so far as to openly criticise the leadership. The most prominent example of this was Bo Xilai, who used his Princeling status to openly identify himself with the New Left movement. This movement, which seeks a return to pre-Deng economics and patriotic “red” ideology, had been largely decentralised, but Bo managed to create a powerbase in Chongqing that combined a powerful patronage network with popular support and his own growing cult of personality. If his corruption had not come to light and disgraced him, it would have been very interesting to see how much of a challenge he would have posed to the Jiang and Hu patronage networks.

The reconsideration of Party politics as based on networks of devolved patronage rather on unified, self-identified factions, allows for more in-depth analysis and leaves more open for future possibilities. Following Mao’s death, all of his top clients fought bitterly to eliminate one another and dismantle or assimilate their patronage networks, with Deng eventually emerging victorious as the paramount leader and ultimate source of all future patronage. Deng’s death saw instead the peaceful creation of two rival networks, headed by his designated successors and chief clients, and if this trend continues over the next few generations of leadership then we may begin to see a considerable difference of opinions between former clients turned leaders of their own patronage networks. Perhaps a form of democracy in China will arise not from the grassroots with the cessation of corruption, but rather from an overindulgence in corruption that affords every powerful political figure the support he needs to voice his opinion and challenge his rivals.