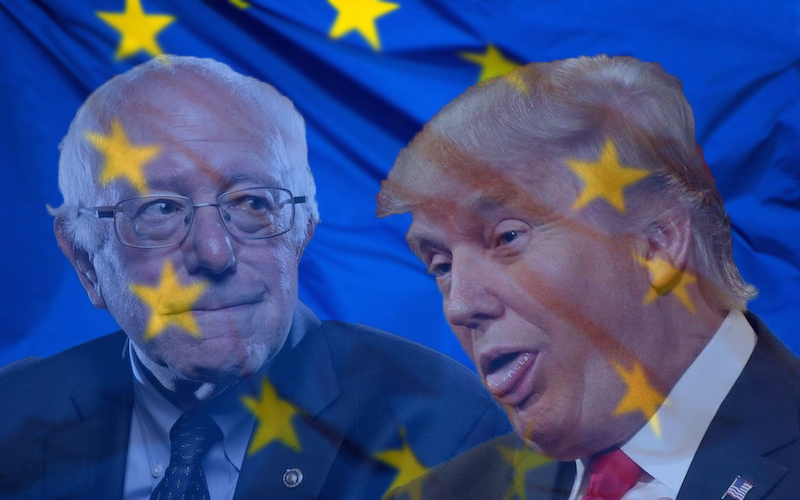

Trump, Sanders, Brexit and the Pandora’s Box of Global Trade

Protectionism, it seems, is experiencing something of a renaissance, on both sides of the Atlantic. The UK’s Brexit vote was partially informed by the desire to give primacy to UK domestic industries rather than the free market. In the US, Bernie Sanders has made it clear that the Democratic Party is against the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TTIP), which, he claims, will result in a “race to the bottom.” On the other side of the aisle, Donald Trump too has indicated that he feels protectionism is the answer to his country’s various economic woes.

Protectionism, especially in times of economic strife, can seem like an appealing prospect, conjuring up motherhood-and-apple pie images of looking after your own. British jobs for British people. American products for American people. Sky-high tariffs on cheap Chinese goods. While all of these might sound like great ideas to the average worker, they will cause more harm than good. Any student of economic history knows the sad story of the protectionist wave of the 1930s, started by the passage of the Smoot-Hawley act that raised tariffs on tens of thousands of goods and led to a tit-for-tat reaction that paved the way for the Great Depression. Such is the law of unintended consequences.

After the events of recent months, the world is standing on the cusp of a crisis of similar magnitude, as anti-establishment forces gain ground. It’s no wonder that the G20 wised up to the ills that a beggar-thy-neighbor approach would cause the world economy, after trade ministers from the world’s major economies agreed to ‘cut trade costs, increase policy coordination and enhance financing.’

But sometimes, even the countries supposedly rallying against protectionist measures are the ones fanning the flames of trade wars. The EU is a prime example of this: through a mix of poorly thought out policies that protect special interest groups, Brussels has managed to cause grievous harm abroad while also crippling economic sectors at home.

Although rarely perceived in this way, protectionism is also a development issue, hitting hardest those who can least afford it. Just look at the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and its impact on Sub-Saharan Africa. Agricultural tariffs on imports combined with generous subsidies for farmers within the EU have led to a massive oversupply of food products, which are then offloaded to developing countries at rock-bottom rates, driving down prices for local farmers who are already unable to sell into Europe unless they reduce their prices to take tariffs into account. In other words, poor farmers in the developing world are doubly undermined by a policy whose sole purpose is to keep European farmers happy at all costs.

In 2012, a report by the Overseas Development Institute looked at protectionism in the EU in granular detail. It argued that despite the fact that the EU claimed its policies would be to the benefit of the poorest developing countries, actually their “research reveals that, in fact, richer nations such as Switzerland and the US will reap the rewards, while EU consumers lose out, and the poorest countries hardly gain anything.”

Interviewed by Debating Europe, Olivier de Schutter, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food and a specialist in European Union law, said that the impact of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy on markets in developing countries has been “tremendously negative.”

Describing the impacts of the CAP, he argued that developing countries “become addicted to food subsidies from the OECD countries. They have developed a dependency that is not easy to get rid of. Were we to decide tomorrow not to export subsidized foodstuffs to the developing world, the result would be severe food shortages in the short-term. “That,” he said “is what addiction leads to.”

The seemingly benign instinct to protect your own markets’ interests quite clearly has malignant metastases elsewhere. And indeed, often at home. Take, for example, the European aluminum industry, a sector that has lost competitiveness and is now threatening to take down with it a sizable number of Europe’s small and medium enterprises. Protectionist measures in the EU, combined with ambitious renewable energy targets and a labyrinthine CO2 emissions trading system have bankrupted many smelters across the continent and completely shuttered Britain’s aluminum industry. In reaction, Brussels imposed tariffs on imports, a stopgap measure that only postponed the inevitable. After China ramped up production and sent global prices in a freefall, EU producers panicked, clamoring for even higher tariffs, despite the fact that this would inevitably harm the very people they are reliant on – their customers. In its efforts to protect its interests, EU aluminum producers were in fact, cannibalizing themselves.

By attempting to protect industries that, due to the march of globalization, are essentially obsolete, protectionism can also risk dragging down high-performing industries with it, and all at great cost to taxpayers. However, it is clear that neither protectionism, nor completely free trade actually can perfectly insulate either the consumer or the economically vulnerable. For many Sub-Saharan countries blessed with plentiful natural resources, free trade agreements would undercut any hopes of economic diversification, as imports would be cheaper than what an embryonic national industry would achieve.

What is needed, perhaps, is a more holistic approach to protectionism. The lid of the Pandora ’s Box of globalization has been lifted and it cannot be shut anymore. Governments should find a way to trade fairly, open to the outside world while also protecting the most vulnerable workers at home through social measures, income transfers and job training programs. Otherwise, a 21st century version of the Smoot-Hawley Act will inch ever closer to reality.