Getting to Yes in Colombia: What it Would Take to Reintegrate the FARC

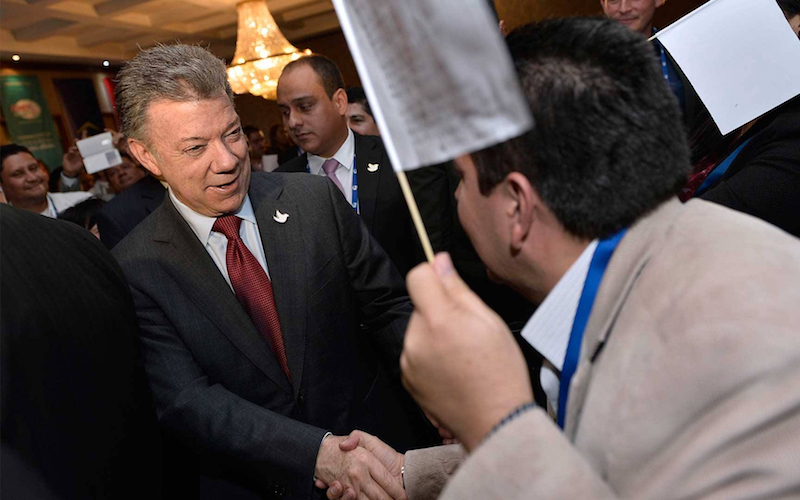

The Nobel Committee has awarded Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos the Nobel Peace Prize.

His key accomplishment was the Sept. 26 signing of the Colombian peace agreement between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, as known as FARC. The signing marked the formal end of 52 years of civil war. In the words of Humberto de la Calle, the former chief government negotiator, the time had come to believe in peace.

But, not everyone agreed.

In a referendum on Oct. 2, 50.2 percent of the participating electorate voted to reject the peace agreement. The voter participation rate was 37.4 percent, with urban centers overrepresented at the polls.

Deciding how to treat the remaining 7,000 FARC guerrillas was a polarizing subject. Some saw the provision of stipends, support, and training to demobilize FARC fighters as an investment in security. Others who opposed the peace accords framed it as a form of rewarding – rather than punishing – individuals for their acts of violence.

Government and FARC negotiators are determining how to adjust the agreement in hopes of achieving a “yes” from the electorate in a future vote. Our combined two decades of research with former combatants and conflict-affected groups in Colombia provide insight into why reintegration is both challenging and significant.

Reconstructing lives and livelihoods

The process by which former fighters lay down their weapons, leave armed groups, and transition back into civilian society is called disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration.

However, as researcher Sami Faltas writes, “unlike disarmament and demobilization, reintegration cannot be imposed or centralized…For this reason, it is usually the weakest link in the DDR chain.”

Although the current reintegration debate in Colombia focuses largely on the FARC, our research covers the experiences of many of the armed actors in the conflict. These include guerrilla fighters from the FARC and National Liberation Army, as well as paramilitary groups.

Reintegration requires former combatants to imagine a civilian life for themselves after a period of time when their livelihood, sense of identity, and community came from affiliation with an armed group.

Disarming and demobilizing ex-combatants often causes them to worry about their security. A former paramilitary member told us, “We know that we’re being tracked down by the armed groups. They send murderers. That’s why I can’t just show my face around town. They’ll kill me.”

Ex-combatants also worry about economic security and their ability to support their families. For some, making money was part of their motivation for joining an armed group. As Vladimiro explained, “In my barrio, when anything is missing – when anyone’s been robbed – everyone starts looking at the people who don’t have jobs. I hated that feeling that everyone suspected me.”

For him, joining the paramilitaries meant receiving a salary and carrying a gun, both of which translated into respect when he walked down the street. The stipend for demobilized combatants is modest, and they become one more poorly paid male among many as they transition to civilian life.

Gender matters

The urgent need to guarantee physical and economic security for demobilizing combatants is frequently tied to former fighters’ understanding of masculinity. The peace agreement addressed aspects of gender. However, it did not explicitly address masculinity or adequately provide for the security of former combatants.

Former paramilitaries have said that their affiliation with these groups helped them “feel like a big man in the streets of their barrios” and allowed them “to go out with the prettiest young women.” In the words of one former paramilitary, “in this country, the man who has a weapon is a man who has power.” Reintegration thus requires reimagining masculinity in a time of transition.

Not all fighters in Colombian armed groups are male. Female fighters, whose exact numbers are difficult to estimate, have joined armed groups for a variety of reasons. Some joined because of past experiences with violence in Colombia. Or, they felt the armed group offered more protection and a more secure livelihood than in civil society. Some were attracted to the possibility of achieving more agency and equality.

While some women experienced forms of gender equality within the FARC, they have also reported experiences of coercion and violence. These have included forced contraception, forced abortion, and separation from children and families. While some armed groups allowed open sexual relations between combatants, sex for female fighters was at times an exchange for protection by higher-ranking males in the group.

When trying to reintegrate, female fighters also deal with stereotypes that portray them as having violated expectations of a peaceful, nurturing femininity. Official DDR programs at times box women into restrictive, narrowly conceived gender roles.

For example, Joshua Mitrotti, the head of the Colombian Agency of Reintegration, said female former combatants have “sometimes lost their feminine features,” and that the program puts “a strong focus on accompanying them and helping them again reconstruct those feminine features they want to reconstruct.” Mitrotti did not elaborate on what a return to “feminine features” may entail for these former combatants.

Stigma and its consequences

The stigma associated with ex-combatants can complicate their employment prospects, social relationships, and sense of identity during the transition to civilian life. The stigma partly stems from people’s concerns that former combatants may slide back into violence, or be recycled into a new armed group or criminal network.

A 2014 study by Fundación Ideas Para La Paz, an independent think tank in Colombia, confirmed that dissatisfaction with reintegration programs and their failure to meet demobilizing combatants’ economic needs can lead to their re-recruitment into armed groups. Weak family ties and social bonds between ex-combatants and the communities into which they enter further affect ex-combatant recidivism.

Collectively, these insights suggest that when disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration programs fail to provide former combatants with an adequate route back into civilian life, the alternatives for these individuals may involve a return to violence. The provisions outlined in the peace agreement included stipends for a fixed period of time, as part of a comprehensive program of reintegration. This assistance may help former combatants with the transition into civilian life.

Justice in transition

Disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration are not solely security issues. Reintegration is also a component of peace-building and justice after armed conflict.

Demobilizing fighters represents a dual challenge: On the one hand, they are reconstructing relationships and identities as they reintegrate into civil society. On the other hand, they are frequently viewed as violent perpetrators who inspire fear in those around them. The broader communities to which they return may rightly demand some accountability for the harms these combatants have caused.

The accountability provisions of the peace accord addressed violence through a tiered system. Demobilizing rank-and-file FARC fighters are eligible for amnesty, provided they were not involved in war crimes or crimes against humanity. Those who exercised command responsibility or were otherwise involved in these grave crimes, including torture, kidnapping and sexual violence, among others, must face the Tribunal for Peace.

At the tribunal, former fighters who confess and fully accept responsibility are eligible for five- to eight-year “sentences of restriction of liberty,” which have a restorative and reparative function, rather than punitive. Those who do not accept responsibility and are found guilty are eligible for sentences of 15 to 20 years.

Critics of these provisions of the peace accord include the former Colombian president and current senator, Álvaro Uribe, his supporters, and José Miguel Vivanco, the head of the Americas desk at Human Rights Watch. In a much-quoted statement, Vivanco dubbed certain provisions of the accord “a piñata of impunity.”

What these objectors miss is the complex definitions of justice among conflict-affected individuals and demobilizing combatants alike. The geographic distribution of the referendum votes suggests that people in regions that experienced high rates of violence voted in favor of the peace accords.

Our research with conflict-affected individuals and former combatants highlights the broader range of justice that operates in war-torn regions of Colombia. It is not simply a dichotomy between criminal justice and jail time, or impunity for the damage former FARC members have done.

What the “no” vote revealed is the deep gap that exists between certain urban centers – whose inhabitants see the war as a distant past, and currently a subject for television series – and people in regions of the country in which the living legacies of war are a part of daily life. In those areas, the peace accords were embraced not for their perfection, but for their promise.

The names of interviewees have been changed for their safety.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.