Science

Why the World Urgently Needs a COP for Cancer

Early in November, more than 3,000 cancer experts traveled to Paris for the 2016 World Cancer Congress. The event was marketed as an opportunity to ‘discuss the latest cancer trends and projections, learn about best practices in science implementation and learn from peers around the world.’ That last is crucial, for at present – despite what the public might think – there is not nearly enough international collaboration in cancer research.

In light of the success of the COP21 in reaching the historic Paris agreement and deciding what needs to be done in order to tackle climate change, it’s high time that the war on cancer saw a similar global effort. Cancer is estimated to cost $1.4 trillion annually, a sum that equals 1.5% of global GDP. On top of that, the disease claims more than 8 million lives every year. Even in rich, developed nations like the UK, many cancer patients lack access to treatment, which accentuates the need for a unified response.

That being said, we also need a heavy dose of realism. In the lead-up to the COP21, no one claimed it would be easy to get 180 countries on board. Cancer does not just face competing priorities or tight budgets but global health bodies that can’t agree on what causes cancer. At the Cancer Congress, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a body of the World Health Organization, released data that suggests alcohol is responsible for an estimated 5% of all new cancer cases. Although this case is compelling, many organizations’ research and findings are not taken seriously.

IARC has come under fire from American lawmakers and international health bodies alike for its panic-inducing assessments that some popular staples cause cancer. In 2015, IARC ranked processed meats alongside smoking and asbestos as known carcinogens. Earlier this year, IARC reversed its 1991 stance on coffee as a carcinogen and muddied the waters for millions of coffee drinkers worldwide. In response to these controversies, U.S. lawmakers are considering ending funding of the agency altogether.

Despite the suspicions with which the IARC’s research is viewed, there is some positive movement in the area of international cancer research. The American Chemical Society has proposed that there should be an international effort, on a similar scale to the Human Genome Project, to identify all the proteins present in cancer cells. They suggest that if this were to happen, within a decade, the results of the new effort could provide cancer patients with more effective, personalized treatments.

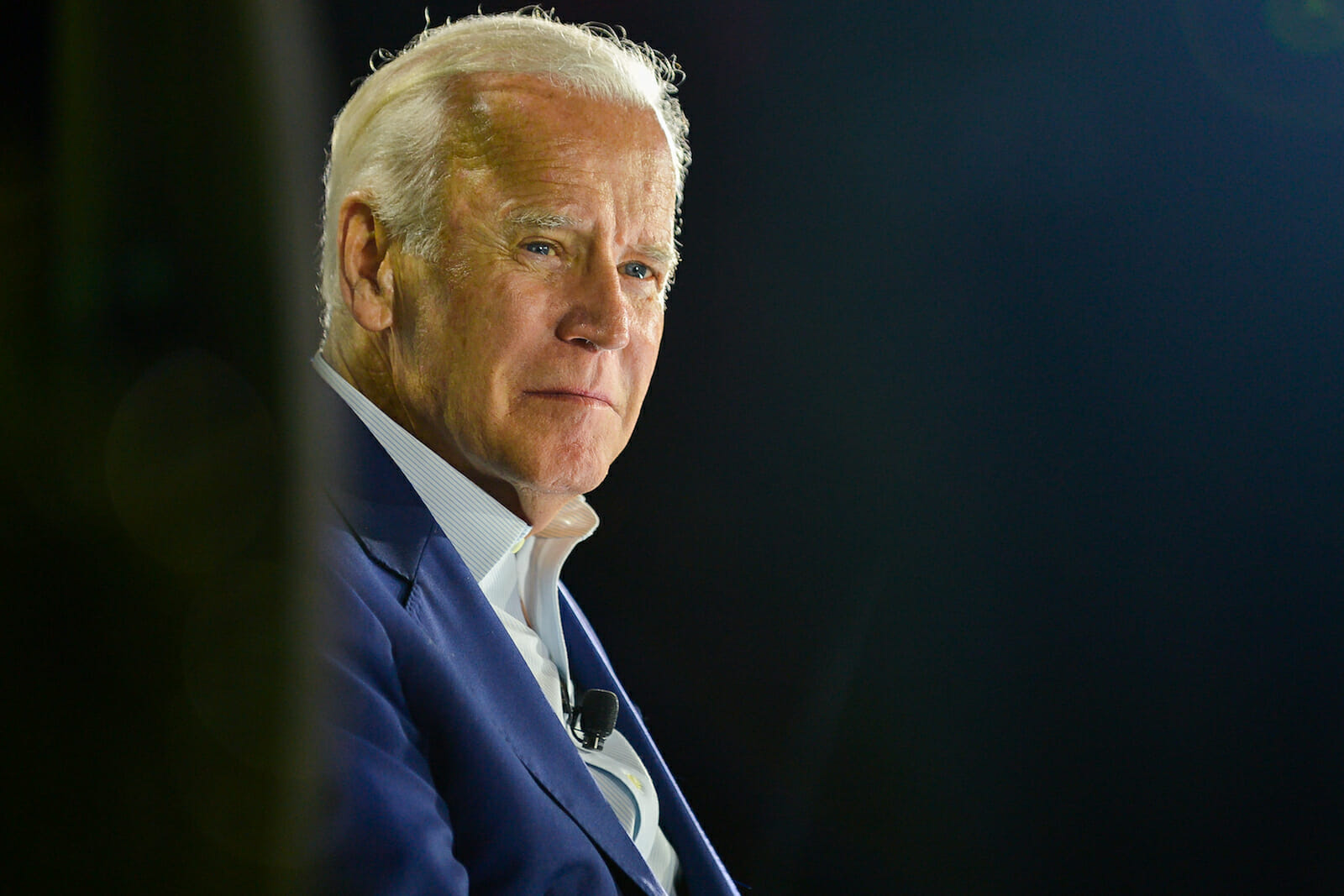

Before Donald Trump’s election, America was at the forefront of the global effort to battle cancer. In his final State of the Union address, President Obama announced a “cancer moonshoot,” a concerted national effort to “double the rate of progress towards a cure and [make] a decade’s worth of advances in cancer prevention, diagnosis, and treatment in five years.” Vice President Joe Biden was given the considerable task of managing this project and has already launched a number of initiatives, including the Tri-Agency Coalition to Enhance Cancer Care – Applied Proteogenomics Organizational Learning and Outcomes (APOLLO) Consortium, which looks at the part proteins have to play in the development and spread of cancer.

Of course, proteins make up only one small part of the jigsaw puzzle. Biden has quite rightly noted that the issue of cancer will probably only be overcome if researchers pool their knowledge and resources globally, saying “imagine what we could do with global sets of patient data to represent the great international diversity of populations, of people, and of cancers.” This is nowhere as necessary as in the treatment of rare cancers, where international clinical trials have the potential to be crucial in identifying effective treatments. Yet for now, Biden must continue to simply imagine a world where such data is collated. Today, global collaboration remains ad hoc.

Unfortunately, some organizations are taking a counterproductive approach to information sharing and dialogue that undermines the vital need for transparency. IARC put itself in this category when it instructed academic experts on one of its review panels not to respect U.S. freedom of information laws by disclosing documents they were asked to be released during the furor about glyphosate, a popular weed killer. Clearly, the current approach isn’t working. The time has come to start working together. Open collaboration is what is necessary to solve this problem, not secrecy.

The fight against cancer requires global research targets and streamlined processes for allocating resources. The global community needs to find better ways to facilitate knowledge transfers, treatment technology, and data sharing in order to more easily assess the causes and prevention of cancer.

Small advances are being made. Cancer Research UK, for example, has launched its Grand Challenge initiative, which seeks to establish international teams of the best researchers in the world to solve some of cancer’s toughest problems. The Economist’s War on Cancer represents small steps in the right direction, but cannot be described as representing a global, comprehensive approach.

History tells us that global cooperation is one of the most effective ways of combatting the disease. As one journalist put it, global coordination has led to “the noose tightening” around polio. Even at the height of the Cold War, adversaries like the Soviet Union and the U.S. managed to join forces to help eradicate smallpox. Cancer is a disease that can affect anyone, anywhere. It’s time the fight against it is borderless as well.