Books

70 years on, Primo Levi’s ‘If This is A Man’ is Still a Powerful Reminder of what it Means to be Human

When he was captured by the Fascist militia in December of 1943, Primo Levi (1919-1987) preferred to declare his status as an “Italian citizen of the Jewish race” than admit to the political activities of which he was suspected, which he supposed would have resulted in torture and certain death.

As a Jew, he was consequently sent to a detention camp at Fossoli, which assembled all the various categories of persons no longer welcome in the recently established Fascist Republic. Two months later, following the inspection of a small squad of German SS men, he was loaded onto a train, together with all the other Jewish members of the camp, for expatriation from the Republic altogether.

His destination, he was to learn, was Auschwitz; a name that at the time held no significance for him, but that initially provided a sense of relief, since it at least implied “some place on this earth.”

Of the 650 who departed Fossoli that day, only three would return. Yet Levi’s magnificent testimony of the Lager, Se questo è un uomo (If This is a Man) – which he would compose in the immediate aftermath of the resumption of his life in Turin, and which was first published 70 years ago in 1947, making it one of the earliest eyewitness accounts we have – is far from a heroic description of his “survival in Auschwitz” (as the American title given to his text would have it). Although in an important sense it is also that.

Indeed, what is striking about Levi’s contribution, still today, is the conspicuous absence of a heroic register from its pages, whose appropriateness in this context – which is in large part what Levi teaches us – must surely be as questionable as the temptation to invoke it is strong.

With characteristic, but unsettling irony, it is the word fortune that appears instead in the very first sentence of his text (“It was my good fortune to be deported to Auschwitz only in 1944…”) and that sets the tone for all that follows. In the camp, it is not virtue that governs fortune; it is fortune that governs virtue.

It is the original title of Levi’s book that in truth gives expression to what will be his principal concern. Yet this is easily misunderstood. It is not exactly a question, and certainly not one that solicits an answer. But it is not even a question whose answer would be provided by the text itself, which claims no such privilege.

As we learn from the poem that opens the text, it must be understood instead to contain an implicit imperative: “Consider if this is man…” It is an order, a command (“I command these words to you”); one that is linked, moreover, to an imprecation:

Carve them in your hearts

…Repeat them to your children,

Or may your house fall apart,

May illness impede you,

May your children turn their faces from you.

It is thus an admonition that we (“You who live safe/In your warm houses”) not avert our gaze. But since Levi, remarkably, includes even himself in this category, it functions also as a kind of self-admonition.

For the description of what Levi calls the “ambiguous life of the Lager” alters our understanding of the very structure of witnessing. And it does so by bringing to light the existence of a distinct oppositional pair much less evident in ordinary life: the drowned (i sommersi) and the saved (i salvati).

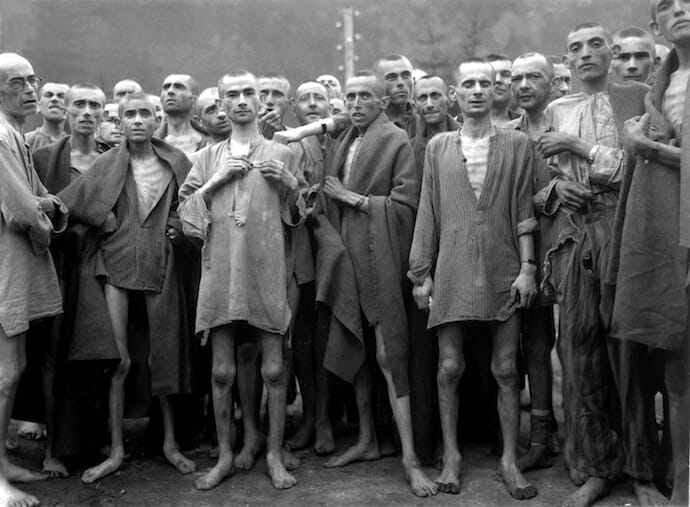

In Auschwitz, all the ritual humiliations appeared as if designed to hasten the prisoner’s descent to what Levi termed “the bottom.” But this process was especially accelerated in the case of those he called the drowned: “they followed the slope down to the bottom, like streams that run down to the sea.”

These were the prisoners who, for whatever reason (and the reasons were many), never adjusted to the brutal regimen of life in the camp; whose time in the camp was thus consequently very brief; yet whose number was apparently endless.

In the jargon of the camp, these were the Muselmänner, the “Muslims,” whose tenuous existence, even prior to their imminent selection for the gas chamber, already hovered in an indistinct zone between life and death, human and non-human. These, according to Levi, were the ones who had truly seen all the way to the bottom: the ones who (as he would later powerfully record) had truly seen the Gorgon.

With respect to the “anonymous mass” of the drowned, the number of the saved, on the other hand, was comparatively few. Yet by no means did it consist of the best, and certainly not of the elect. To invoke the guiding hand of providence in the midst of such atrocity was nothing short of abhorrent to Levi.

He is unflinching on precisely this delicate point: with rare exceptions, the saved comprised those who, in one way or another, whether through fortune or astuteness, had managed to gain some position of privilege in the structured hierarchy of the camp.

More often than not, this entailed the renunciation of at least a part of the moral universe that existed outside the camp. Not that the saved, any more than the drowned, are to be judged on this account. As Levi insists, words such as good and evil, just and unjust, quickly cease to have any meaning on this side of the barbed wire.

It was nonetheless his conviction that those who had not fathomed all the way to the bottom could not be the true witnesses. Yet far from invalidating the survivor’s testimony this made it all the more urgent.

According to Levi, it is the saved who must bear witness for the drowned, but also to the drowned. For in him is mirrored what he himself saw.

“Consider if this is a man…”: the imperative issued by Levi’s text is thus not that one should persist in seeing the human in the inhuman. It is more like its opposite: that one bear must witness to the inhuman in the human. And that our humanity in some sense depends on this.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.