Legally Speaking, Can an Elephant Tusk be Anything Else?

I was in a Mombasa courtroom yesterday listening to a case from 2018 where two ‘gentlemen’ were snagged in a car heading to Mombasa with 37 kg of ivory. One of the witnesses was a scientist from the Nairobi National Museum who was testifying that the 37 kg of ivory seized was actually ivory. This is normal procedure. In Kenya, when Kenya Wildlife Service or the police make an ivory seizure the ivory is sent to scientists at the Nairobi National Museum for identification purposes. The scientists then examine samples of the seized tusks under a microscope, looking in particular for ‘schreger’ lines, and make the determination that yes, these tusks or these bangles are definitely ivory.

So on this particular morning, while listening to his rather non-exciting testimony, I had a thought. Do we really need a scientist from Nairobi to travel to a Mombasa courtroom to tell the Magistrate and the court, that yes, the tusk-like objects found in a vehicle within a modified hidden compartment driven by the two accused while also in possession of a hack saw, was actually ivory.

Now, I admit that the photo above of that particular seizure is not clear for the purposes of my argument, with several of the tusk points buried in the pile, but when you think about it, can elephant tusks be anything but elephant tusks? Is there anything else in our world that looks like an elephant tusk?

Below is a photo of an ivory seizure made in July of 2019; 182 kg of ivory allegedly found in the custody of the ‘gentlemen’ in the photo. The seizure was made in the Kilifi area. Roughly a 2 hours drive north of Mombasa for those wondering where that ivory may have been headed.

So, the question hangs. Is there anyone residing on the planet, in 2020 and above the age of 2 years old, that could not have walked into a courtroom and told the Magistrate that the items depicted in the photograph were elephant tusks?

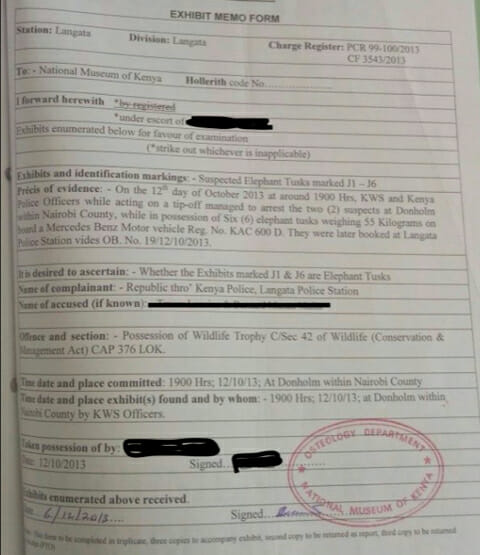

Let’s drill down into this process a little more. When the ivory is seized, the first thing the officers will do is complete an exhibit memo (below) requesting the Nairobi National Museum to examine the ivory. It will detail who will escort or transport the ivory. The ivory will then be transported from wherever in the country it is seized to Nairobi. In this particular case, it will take two officers or rangers 9-10 hours (on a good day) to complete the drive. They will leave the ivory with the Osteology Section of the Zoology Department of the Nairobi National Museum.

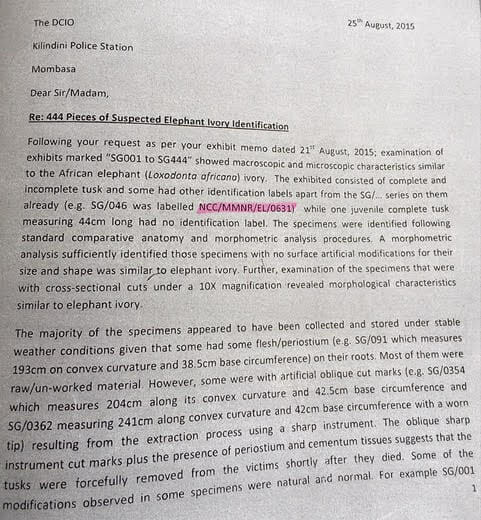

The scientists will examine the ivory and complete a report. This report is of particular note as it shows that one of the seized tusks has markings indicating that it had been seized previously by police or KWS in Narok County. This, of course, means that this piece of ivory somehow found its way out of police or court custody and back into the hands of the bad guys. Which reminds me, didn’t the police arrest a Narok court administrator last September 2019 for selling ivory court exhibits? But I digress.

When the scientific examination and report is complete, the investigative authority is notified and they will return to the Museum, sign for the ivory exhibits and return to their home station. As detailed in this report, it was for almost 2 months that this ivory was in the possession of the Museum for the purposes of “ascertaining whether exhibits marked J1 and J6 are elephant tusks.”

Finally, when the case comes up for hearing, the Nairobi scientist who examined the ivory, will be required to travel to whichever court in the country is hearing the case, to testify that yes, these elephant tusks, that even a small child could identify, are really elephant tusks.

To be fair, there are certainly occasions when a scientific eye may be required. If ivory has been worked into bangles, chopsticks, or jewelry, it is an obvious necessity. I am sure there will be a day when a mammoth ivory or ankara cow horn defence will be introduced and scientific examination will be required. But those cases are the few, the majority of ivory seizure cases involve readily identifiable tusks, something that even the greenest ranger should be able to attest to. We are not talking cocaine or marijuana that can be and has been seen as glucose or herbs or similar. And yes, it is recognized that Bryan Christy of National Geographic once had an imitation tusk made, at a substantial cost I am sure, but that would have to be considered an anomaly to the extreme.

Solutions

So in a time when KWS and the Kenyan judiciary are in a period of financial distress, (OK, probably serious understatement) let’s look at the substantial impact that could be made on cost, man-hours and mitigating corruption risk if the judiciary could agree that maybe there isn’t a need for an Osteologist in all ivory cases:

- Man hours, transportation and accommodation costs relating to ivory going to Nairobi National Museum for over one thousand cases.

- Costs incurred for scientific examination from the National Museum to examine ivory in over one thousand seizures.

- Court costs incurred of transporting/accommodating that scientist to whichever court is hearing the case, bearing in mind as well, the likelihood of adjournments and the scientist having to return to the court.

- Minimizes chain of custody issues with the ivory exhibits.

- Reduces court time by eliminating a witness.

- Frees up thousands of hours of time for the scientists of the Osteology Section of the Zoology Department at the Nairobi National Museum.

I am sure there are lawyers who will argue that an expert is required to identify an elephant tusk. For those, there are two compromises that could be made. The judiciary could allow the prosecution and the defence to have a pre-trial agreement that does not dispute the substance is ivory thereby negating the need for scientific analysis and expert testimony. In addition to this or in lieu of, the courts could permit a KWS officer of certain experience to say that the elephant tusk is an elephant tusk thereby again eliminating a substantial cost in man-hours and dollars.

Or we can revert to common sense and the realization that there is nothing in nature that quite replicates the tusk of an elephant. Don’t even children know that?