How COVID-19 Will Impact Saudi Arabia’s Patronage-Based Economy

Despite its wealth, economic sustainability, and geopolitical influence, COVID-19 has not spared Saudi Arabia. Not even a pot of black gold will give the Kingdom immunity.

The pandemic’s tremendous economic destabilization highlights the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s (KSA) seemingly forgotten poor. Bold economic restructuring plans like Mohamed bin Salman’s (MbS) Vision 2030 had provided a portion of the Saudi population hope for more open channels of economic prosperity. However, COVID-19 continues to pose a great threat to the application of Vision 2030 and, by extension, prevents the Saudi urban poor from benefiting from the welfare state.

Vision 2030, implemented in 2016 by Mohamed bin Salman, intends to set the Kingdom on a new social and economic trajectory. Considering the KSA was dangerously dependent on constantly fluctuating oil revenue, KSA leaders sought to diversify the economy to ensure sustainability. By 2030, MbS seeks to increase tourism and improve infrastructure, reorienting its revenue channels to mirror some of its successful neighbours such as the UAE and Qatar. As of 2016, oil profit accounted for 87% of Saudi budget revenues. As a point of comparison, Russia, the second-largest world exporter of oil, only attributes 40% of its revenue to oil.

Arguably, Vision 2030 was catalyzed by the nearly 50% global price drop in oil in 2016, bringing it from $100.00 a barrel to $50.00 and emphasizing the cruciality of economic diversity. Its urgency was further highlighted when COVID-19 and its unintended economic consequences brought oil prices down to $30.00 on March 20th, the lowest price since 2003. Since this article was published, oil prices have dropped below zero. This fluctuation combined with record-breaking low oil rates is further pressing the need for Saudi Arabia to develop additional and reliable streams of income.

The global health crisis has sent a number of states, Saudi Arabia included, running to provide stimulus packages as their economies have found themselves in disarray. The dire economic consequences are exposing how reliant KSA is on this model even under normal circumstances and its difficulty adjusting to the change. COVID-19 has made the expansion of economic stimulus and welfare programs essential for survival in a number of nations during the critical moment of KSA’s economic structural transition. Saudi Arabia is a prototype of the rentier state, an economic structure enabling the country to throw money at its population because of its tremendous oil wealth. Rentier states, commonly found in the MENA, are states rich in natural resources and allocate revenue coming from said resources to build the economy. Rentier economies require limited public taxation to fund infrastructure and provide social services. Rather, the rentier structure uses oil revenue generated from the international market as patronage to strengthen the state.

Vision 2030’s focal point was transforming the rentier state—entirely dependent on oil revenue—to a more market-centric economy. An increase in taxation and expansion of private-sector employment would come with this transformation. Economic impacts of COVID-19 will sever the rentier state, but they will also halt the transition to market and taxation-based revenue streams.

Two-thirds of employed Saudis find themselves in public sector jobs. A number of these jobs are in Aramco—the nationalized oil company—enforcing the relationship between personal welfare and oil prices. Vision 2030 intends to reduce the number of public sector employees to 20% of the workforce. Since 2016, a number of provisions have been outlined to achieve this, such as pay cuts for public sector employees; reducing subsidies for fuel, natural gas, and water; and introducing a 5% tax on goods and services which sent prices of basic commodities soaring, along with the number of middle-class families finding themselves in impoverished situations. Cutting pay and increasing taxes have the effect of forcing people into further poverty. With growing distance from the rentier system combined with COVID-19’s impact on revenue, the ability for the Saudi government to combat poverty with charity-like methods decreases. Not to mention that the practice of politicians simply throwing money at a problem is rarely successful in the long term.

Transitioning to a more private sector-oriented economy could not have come at a worse time for the Saudi lower and middle class. Garbis Iradian, the Chief Economist for the Middle East and North Africa at the Institute of International Finance (IIF) highlights that high oil prices are essential for spending and thus developing the non-oil economy.

Furthermore, Vision 2030 sought to decrease unemployment to 7%. With the recent slowdown, unemployment will likely rise to 13% for 2020, a .5% increase from 2019. Meanwhile, the national labour force is increasing because of the rise in female labour participation, a quickly actualizing goal of Vision 2030.

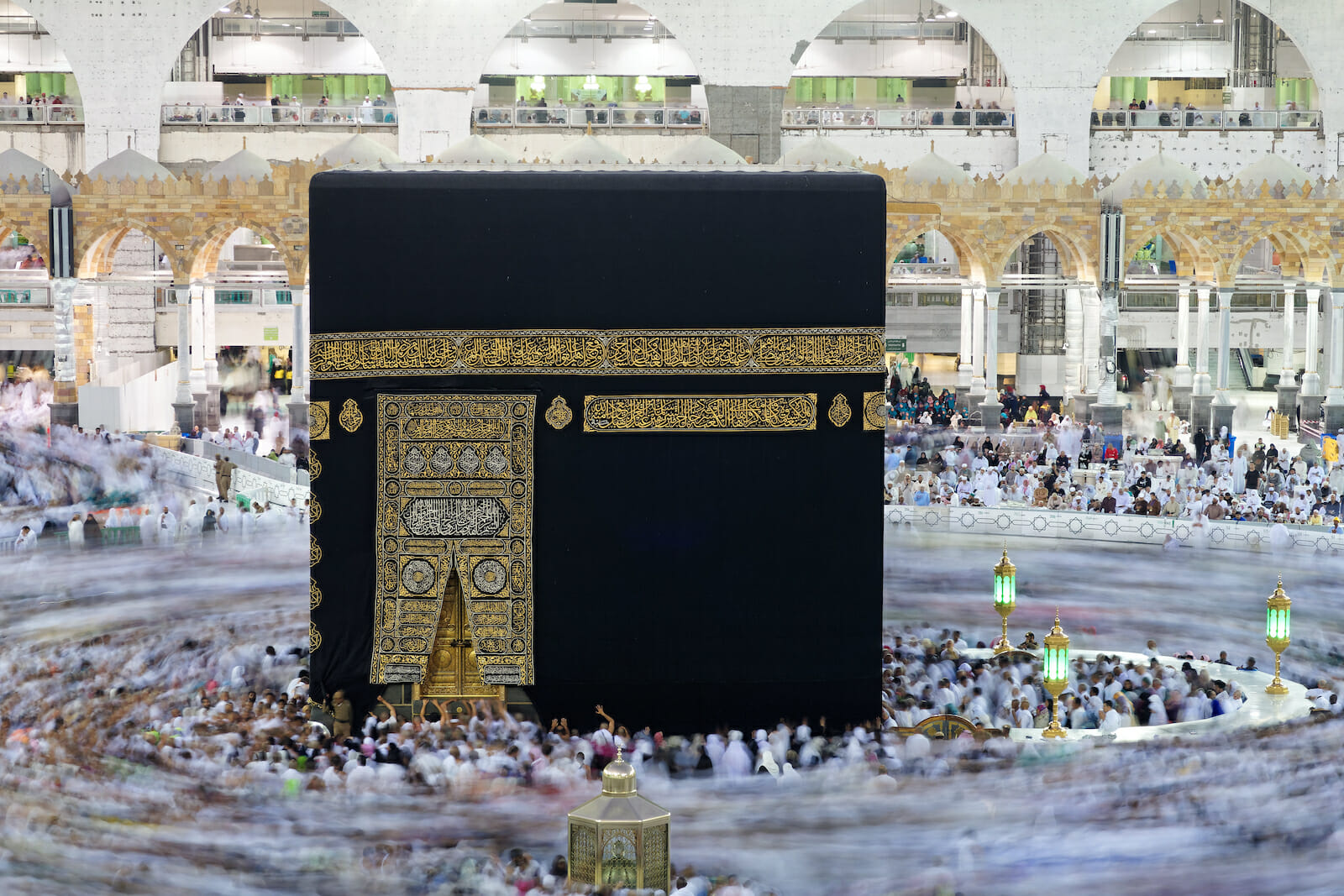

In light of the pandemic, KSA suspended a number of flight routes in and out of the country and plans to prohibit the entry of religious pilgrims embarking on the Hajj—the Islamic pilgrimage to the holy land of Mecca—set for this upcoming summer. Around two million Muslims attend the Hajj each year; this year’s potential cancellation will create financial implications for private industries associated with it like hotels, restaurants, and transportation services.

Cutting public sector employment alongside a decrease in the ability for the private sector to continue employing individuals will plunge much of society into poverty, including populations who did not find themselves in paycheck to paycheck circumstances before the pandemic.

It is reasonable to conclude that the Saudi poor have no access to the patronage system; after all, what can they provide to a wealthy monarchy? The royals do not need to appeal to the poorer classes for support, considering that the current political structure is far from a democracy. Therefore, the revenue the KSA is able to hand out as a rentier state is allocated to those closest to the regime—powerful voices who will remain loyal to it despite external factors fostering economic and social turmoil. There has yet to be talk of the KSA handing out grants to the unemployed as has been discussed in Canada and the United States.

The Saudi image of an abundance of wealth is reflective of a small portion of the population and intimately linked to an unfair system of fund allocation. Saudi infrastructure, that of hospitals and schools, remain dependent on the oil wealth of the rentier system. As this revenue decreases in the face of COVID-19, the ability to keep social services and infrastructure for the poor and successfully transition the economy will be severely hampered. It is unlikely that in the wake of the global pandemic, the Saudi government will begin prioritizing its lower-class population, leaving the demographic in cyclical poverty despite the Kingdom’s promise of economic opportunity.

COVID-19 struck at the exact wrong time for a state looking to roll back welfare and build a private marketplace. If KSA doesn’t change course soon, the poor and middle class will be left in a lurch as the rentier state stimulus recedes and there is no market to replace it.

This article was originally posted in the McGill International Review.