Two 90s Kids Talk ‘The Last Dance’

The following article contains spoilers for The Last Dance.

Will Mann: So I guess to get started, speaking as someone whose own personal expectations were blown away, what were your expectations going into The Last Dance? I had heard a lot of good buzz about it, and it had the prestige of being a co-production between both ESPN and Netflix. It felt a lot like ESPN’s acclaimed 30 for 30 documentary series, which, along with a sister series called Nine for IX, focused on women in sports, has been credited for being very analytical, comprehensive oral histories of major moments and people in contemporary sports history. The 30 for 30 label is responsible for projects like the incredible Academy Award-winning documentary O.J.: Made in America, as well as a family-favorite episode entitled “Pony Excess,” which is about the “death penalty” the NCAA imposed on my mother’s alma mater, Southern Methodist University. Though I don’t think The Last Dance comes from that label specifically, it is clearly very influenced by it.

Also, admittedly, basketball really isn’t my sport. But, especially in unprecedented times, I craved the nostalgia of seeing the Chicago Bulls in the 1990s. Growing up when we did, you knew that they were the team, and whether it was from commercials, apparel like Air Jordans, watching him play, or in my case, countless viewings of Space Jam, you knew that no one on Earth could match Michael Jordan. I thought this would be a pleasant trip down memory lane, the equivalent of the “member berries” from South Park. I think what shocked me the most was that it brought that 30 for 30 level of detail and insight, but also had a central thesis about what it wanted to be about, what it wanted to answer: “why this team at this time?”

Joel White: For me, watching The Last Dance was a singular delight, not least of all because it somehow managed to calmly exceed my already high expectations. I may be a nerd’s nerd, but make no mistake–I keenly follow sports, too. I was brought up in a household that loved and lived athletics. My parents were both jocks (I use the term affectionately), and even if baseball was their first true love, my dad made sure there was plenty of basketball on the TV, too. And in the 1990s, that could only mean one thing: the Chicago Bulls. They weren’t just the darlings of the NBA; they were The Team, the crown jewel of all sports. And Michael Jordan was The Man. And I do love a great story. So I had high hopes for The Last Dance. I was expecting it to serve up a fresh take on arguably the greatest sports story ever told, all with a heaping helping of ’90s nostalgia on the side. And boy did it ever.

The Last Dance gives its viewer a comprehensive, start-from-the-very-beginning chronicle of one of the greatest teams ever assembled in any sport. It sheds light on storylines you probably didn’t even know were part of that saga, bringing in interviewees ranging from Terry Francona to Bill Clinton. It paints such a complete and intimate portrait that, past a certain point, all of the action captured in the archival broadcast footage starts to feel downright personal. That makes The Last Dance not just a good sports feature, but damn fine documentary work in its own right.

Mann: I completely agree, and I think that it succeeds because it leaves no stone unturned. I think it’d be easy to simply be powered by everyone’s collective nostalgia for the 90s Bulls, but uncomfortable truths are confronted and various controversies are explored. Take the way the documentary portrays Michael Jordan, for example. It’d be easy to make Jordan simply the figure of hero-worship, but issues like his gambling are directly addressed. Moreover, there are times when Jordan comes off as a seemingly not-nice guy, and is particularly demanding of his teammates. The documentary doesn’t shy away from that, whereas I feel like in less capable hands, maybe there would be a tendency to sweep that under the rug. Obviously, The Last Dance is ultimately praiseworthy of Jordan, while still maintaining a critical approach. This is also true of Dennis Rodman, who certainly doesn’t do much to alleviate his infamous party-boy persona. But the advantage it has are the flashbacks to Rodman’s personal history, because you understand where he came from and how he became a great player. Now there’s a context for why Rodman is the way he is, which means you can’t just dismiss him outright.

Some of the players have outright tragedies in their lives, the show depicts Jordan’s deep mourning after his father passes away sensitively. Former Bulls point guard and current Golden State Warriors coach Steve Kerr might have the most tragic backstory, as his father was killed by terrorists while serving as a university president in Lebanon. Understanding the backstories to these players is crucial to understanding the underlying thesis of the show.

Are there any people in the documentary who grew in your view of them? For me, the answer is definitely coach Phil Jackson, whose Zen-like approach to coaching on the court was a unique asset, as well as Scottie Pippen, who emerges not just as Jordan’s right-hand man, but a crucial element without whom neither Jordan nor the Bulls would have been quite as successful.

White: “No stone unturned” is exactly the right way to describe this documentary. Every moment of the 1997-98 Bulls season–itself the capstone of an epic run of success–is presented as the culmination of someone’s lifelong journey. Past a point, you start to get the feeling that everyone involved with that team was born for the exclusive purpose of bringing the city of Chicago its second three-peat of the decade. One person who stood out to me was Steve Kerr, a man I already respected as the three-time championship-winning coach of the Golden State Warriors. I admittedly did not know what a pivotal role he played in the back half of the 90s Bulls dynasty, particularly in the 1997 Finals. And I certainly had no idea that he was the son of an academic who was tragically murdered overseas. The Last Dance presents Kerr as an overlooked player–not heavily recruited by college programs, not a highly touted prospect upon his entry into the NBA–who made up for his lack of wow-factor talent with hard work and determination. As of today, he is an eight-time NBA champion: thrice with the Bulls, twice after being traded to the San Antonio Spurs, and then thrice again as a coach. That’s as impressive a resume as anyone on that 1998 Bulls team. And I say that fully aware of who else falls into that category.

On the opposite side of things, I should also note that The Last Dance does an excellent job of portraying Bulls General Manager Jerry Krause as a kind of overarching villain. Krause is ever the businessman, emphasizing the primacy of organizational competence over all-star talent, putting Phil Jackson on a short leash to minimize risk, and ready to jettison his core players for the sake of a team rebuild (which, I should note, he did follow through on). The way we see Jordan and Pippen treat him in archival footage–constantly and casually poking fun at his height and weight–both reinforces his status as an antagonist and makes you like the players a little less. That’s effective storytelling by any measure, something The Last Dance displays in spades.

Mann: I completely agree regarding Steve Kerr, I think he emerges as a pivotal player alongside the more obvious Jordan, Pippen, and Rodman. And you’re also right about Jerry Krause, he’s the closest thing the documentary has to an antagonist. When you mention how instrumental Kerr was to the Bulls’ 1997 championship, that actually reminds me of one of my favorite aspects of the show, which was using the 1997-1998 titular “last dance” (which derives its name from what Phil Jackson named the team’s strategy for that year) as a frame narrative to explore the Bulls’ five previous championships. The one that stands out in my mind is the first one in 1991 where the Bulls won against the Lakers and their star player Magic Johnson, because the image of Michael Jordan clutching his first championship trophy while crying is likely to stick with anyone who watches. The show frames this victory as one that puts Jordan and the Bulls on par with the other great players and teams in NBA history.

The comeback championship in 1996, which happened after Jordan had seemingly retired to play baseball after the death of his father and then returned to the Bulls, was another impressive victory. It was a close series against the Seattle SuperSonics (now the Oklahoma City Thunder) that, again, the show presents as something that proved the doubters wrong. It would be easy to simply reflect on the nature of the ’97-’98 season, but the fact that The Last Dance takes this opportunity to explore what led the Bulls to that point is beyond commendable.

Were there any small moments that stuck with you? Besides a great moment where a young Leonardo DiCaprio, basking in the fame of the then-recent Titanic, meets the Bulls after they won the championship in the locker room, I think of things like the 1992 Summer Olympics U.S. men’s basketball “dream team.” While not entirely pivotal to the plot, that segment embodies the theme that Jordan helped make basketball a more globally popular game, as evidenced by the massive billboard of him in the Olympic host city of Barcelona. You also get a glimpse of Jordan and Pippen playing alongside other icons of the era, including Magic Johnson, Charles Barkley, Karl Malone, Larry Bird, and Patrick Ewing, many of whom are interviewed throughout the series.

White: In spite of its overall focus on the larger-than-life heroics of Jordan and Pippen, the small moments that you’re referring to are where The Last Dance really shines. Borrowing somewhat from your Dream Team example, I find myself reflecting on the mini-storyline surrounding Toni Kukoc, the star of the doomed Croatian national basketball team from the ’92 Olympics and, incidentally, the Bulls’ most important bench player throughout their second three-peat. He’s someone you’ve probably never heard of (I certainly hadn’t), and yet The Last Dance plucks him out of obscurity and seamlessly integrates him into the narrative leading up to the 1998 championship. He becomes another one of those players whose destiny pulls him inexorably toward that fabled last season. In particular, he’s featured in a really nice moment from the ’94 conference semifinals where Phil Jackson, over Pippen’s vehement objections (he sat out the play), designs a play around Kukoc that gives him the chance at a huge game-winning shot. And in a display of icy clutch, he delivers. It’s a small story brilliantly told–it shows you that a member of this dynasty as obscure as Toni Kukoc is still an indispensable part of the narrative of the unbeatable Chicago Bulls. (Of course, they went on to lose that series in 1994, because someone was off playing baseball.)

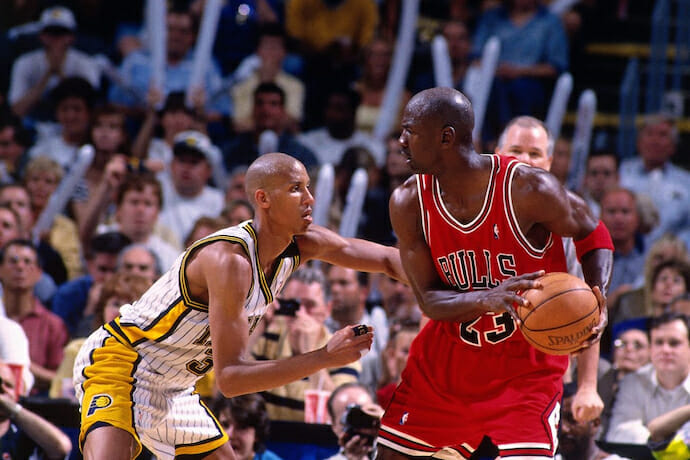

One other small moment I’ll mention, just because I got such a kick out of it: that clip of (then-Indiana Pacers coach) Larry Bird as Reggie Miller hits the go-ahead shot in game 4 of the ’98 conference finals. The crowd goes nuts, but Bird – fully aware that there are still 4 seconds left on the clock and Michael Jordan was going to get a chance at one last shot – is completely deadpan. It’s so funny to watch and such an effective storytelling moment at the same time.

Mann: I’m in agreement about those little moments, there are a lot of them, and I think it speaks to the idea that The Last Dance has this impressive balance between focus and scale. When your story is one of the biggest sports stories of the last century, I think there’s a tendency to only focus on the macro, the larger scale stuff. But those intimate moments where we see the veil lifted, I think that’s something that distinguishes The Last Dance and makes it stand above what a lot of other comparable, contemporary documentary TV shows do. When you watch Tiger King, for example, you know you’re basically watching a train-wreck, and that show definitely wants you to feel a certain way about the various people on the show. Just ask Carole Baskin. The Last Dance is smarter because it presents you with a comprehensive recounting of this story and wants you to draw your own conclusions. One friend told me that while watching the show, he felt like Michael Jordan reminded him of both Miles Teller’s and J.K. Simmons’ respective characters in the movie Whiplash, this contradictory idea of both the harsh teacher and sensitive student being the same person that happens to make a lot of sense.

I began by talking about the show’s central thesis, “why this team at this time?” So it makes sense that the conclusion one would draw from it would be subjective. Ultimately, I think part of what makes The Last Dance stand out is that it is a portrait of a team performing at the absolute pinnacle of achievement. So as we conclude our conversation, I want to ask what are your conclusions, your takeaways? I also wanted to ask why you thought this broke out big? Was it simply nostalgia? Was it merely the quarantine, we were stuck inside with no sports to watch and then this came out, or is there something more to it? And finally, is this a milestone, for TV, for documentaries, and for sports documentaries in particular? Will other documentary TV begin to follow in its footsteps? I know that Ken Burns, for one, has been critical of having the subjects of the documentary participate in the production of it.

White: “Why this team at this time?” is, I think, a question with a much more straightforward answer than “Why this documentary at this time?” The Last Dance definitely wants its viewers to come up with their own response to that first question, but the producers seem to be hinting at a fairly simple explanation: Because it had to be. The way they tell it, there was simply no possible reason for Michael Jordan, Scottie Pippen, Dennis Rodman, Steve Kerr, and Phil Jackson to assemble other than to win a world championship, even if they had just done that five times in the previous seven years. (If anything, that last statistic just bolsters their point.)

But that second question of why exactly did this documentary hit it so big probably doesn’t have just one neat explanation. My guess is it’s a combination of everything you mentioned. Since March, most Americans have been stuck in their homes, cooped up and deprived of travel, camaraderie, and – most crucially – live sports. That, combined with the notable predilection us ’90s kids have for nostalgia, created a perfect storm of longing for which The Last Dance proves to be a mightily effective tonic. I hesitate to say this is some kind of watershed moment for documentaries or television, but I do think The Last Dance has the potential, much as Michael Jordan himself did, to introduce the NBA to new audiences who might not have otherwise been exposed to basketball. I wouldn’t be surprised if viewership for the ongoing NBA playoffs were a tad higher right now than it was last year. (Although that could have just as much or more to do with quarantine.)

As for the subjects of The Last Dance being involved in its production, I think there is good reason to be wary of that sort of arrangement, but I also think that can make for some darn good storytelling. Take Rocketman, the Elton John musical biopic that was released to such acclaim last year. It’s an excellent film – flashy, kinetic, and beautifully staged, shot, and acted – but it was co-produced by Rocket Pictures. I’ll bet you can guess who owns that company. And I’m content to let larger-than-life figures like Elton John and Michael Jordan help tell their own stories. When you’re that big, there isn’t really one truth anymore. Only legend.

The Last Dance is available on Netflix.