How to Sell Solar Panels to a Cowboy

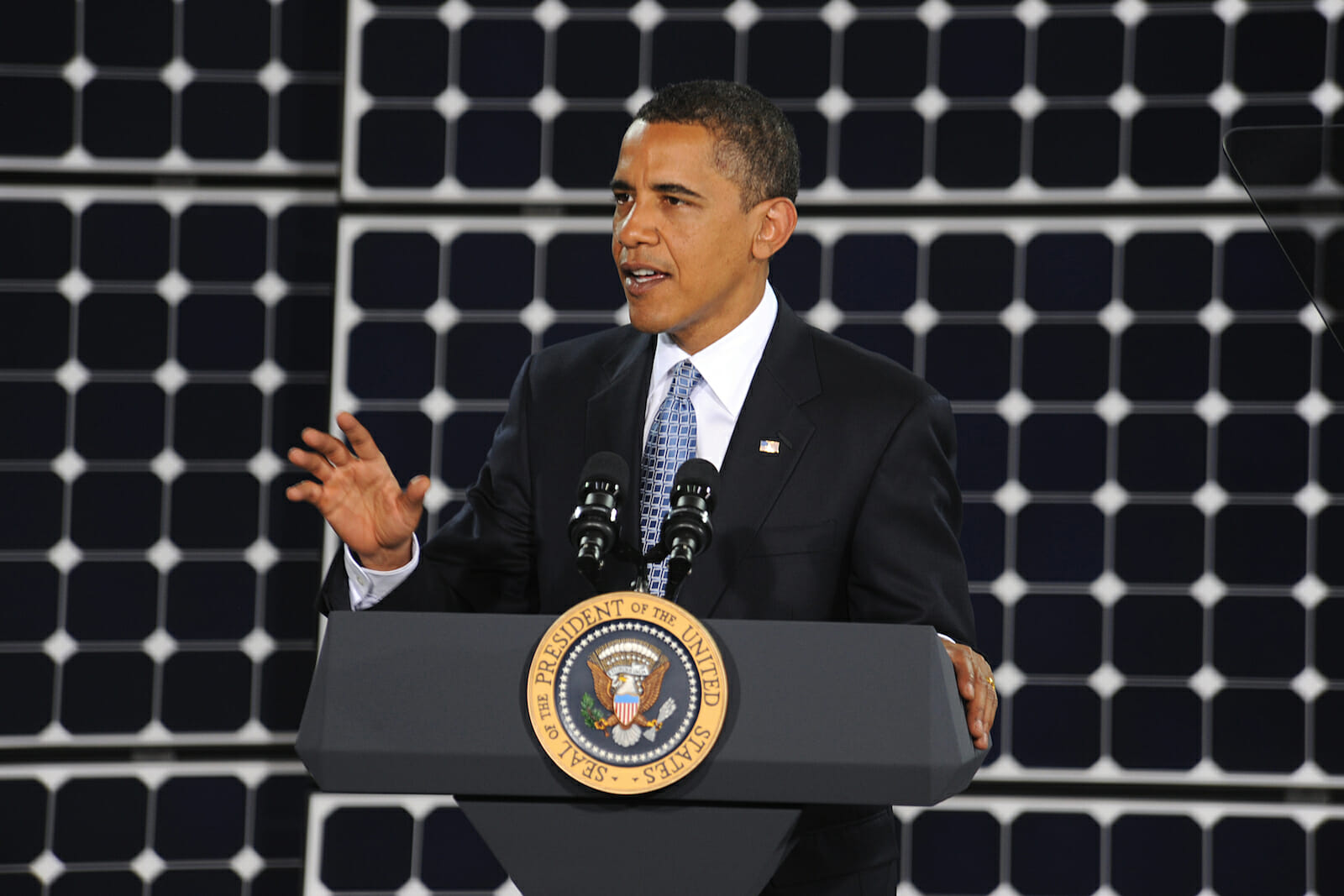

President Barack Obama now enjoys renewed political popularity thanks to his national security policy. As his field of 2012 GOP competitors winnows, Obama seems assured of re-election. His supporters among the national environmental movement will surely pressure him to act boldly and swiftly on energy policy reform. This summer is an ideal policy window for the White House to roll out a green economic stimulus package.

Memorial Day marks the start of summer driving season when Americans will curse $4/gallon gas and $100/barrel crude, and open their minds to energy alternatives. Legions of recent college graduates work at part-time or temporary jobs, waiting for just the sort of excitement generated by the renewable energy sector. By this time next year, Obama’s antagonists in Congress and the federal bureaucracy will begin to think they can simply run out the clock. The policy window will have closed.

The White House has made green gestures of late—attempts to scrape the tax code clean of favors for fossil fuels. The Senate recently rejected an administration-backed Democratic proposal to end special tax breaks totaling $21 billion over ten years for the country’s top five oil companies. But the promise of clean, high-tech, safe energy from solar, wind and geothermal sources requires public salesmanship of comprehensive legislation. Symbolic bills like S. 940 should be part of a larger communications strategy, not an end in itself.

The White House should introduce a comprehensive clean energy plan with language rooted in the most fertile of metaphors. American political culture thrives on the sound bite symbol, from tea partiers to mama grizzlies to a John Kerry protester dressed up as a dolphin with a sign saying, “Hey Kerry, I’m a Flipper, too!”

Presidential speechwriters, like the one who devised “Axis of Evil” for George W. Bush, can coin new symbols that set the terms of debate and shape policy. Powerful metaphors can also flow from folklore. The American frontier myth has scripted our history of fossil fuel hyperconsumption. Since the Revolutionary War, frontier bedtime tales have scrambled men and boys into the wilderness, their guns cocked, ears pricked, and eyes fixed on the Western horizon. The bonanza was born on the 19th-century frontier—droves questing after cheaply mined, precious gold and silver. When a rock would give no more of its wealth, frontiersmen moved West, leaving the polluted desert for those without the bones for another journey.

J.M. Peck’s 1836 A New Guide for Emigrants to the West described the typical scenario, “He builds his cabin, gathers around him a few other families of similar tastes and habits, and occupies till the range is somewhat subdued, and hunting a little precarious, or, which is more frequently the case, till the neighbors crowd around, roads, bridges, and fields annoy him, and he lacks elbow room.”

Historian Vernon Louis Parrington called Davy Crockett “a true frontier wastrel…one of thousands…destroying forests, skinning the land.” The dirtiest of coal-fueled the transcontinental locomotive’s path to the Pacific. Western expansionist and explorer William Gilpin claimed the railroads would lead pioneers to gold “infinite in quantity.” The 20th century saw the ecstasy of the first oil boom and presidents as diverse as Theodore Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan exploit frontier imagery for political persuasion.

The hero of the frontier, the cowboy, is an icon of American political behavior, from foreign policy to the environment. This decade, Al Gore, John McCain, and Barack Obama have tweaked the frontier metaphor to promote sustainable energy, calling for a new “Apollo program” for clean energy innovation. But resource exhaustion at the frontier is historically rapid, chaotic, and violent—just the opposite what advocates envision for a renewable energy economy. Jimmy Carter tried to engage the populace around energy crisis with martial language: the “moral equivalent of war.” Yet Carter’s energy plan stalled in Congress. Even after passage, it failed to move the press or the public.

The patriotic symbolism of the pioneer family farm, an image akin to the frontier, can better sell skeptics on solar, wind, and biomass. Agriculture inherently produces biomass energy sources like crop residue, livestock waste, and energy-dense grasses. Communications consultants for the solar and wind industry will tell you, it’s the technical aspects of their trade that alienate many otherwise sympathetic consumers.

Solar engineering requires an advanced degree; carbon combustion is common sense. The image of the working farm is just as simple as the oil drill or coal furnace. The life cycle of the farm mirrors that of the solar plant—line by line of cells, harvesting the sun to store energy. Like an Iowa corn farmer, a solar plant operator strives to maximize yield per acre. Success in both trades requires a keen weather eye.

We already call large-scale wind installations “farms,” and many turbines provide supplemental income to actual family farms in the country’s heartland via lease payments. Horizon Wind Energy’s Meadow Lake Wind Farm towers over verdant Indiana cornfields—integrated into the pastoral portrait as much as a barn or grain silo.

Williams Jennings Bryan led rebellious farmers into the Democratic Party by dint of his silver-tongued oratory. George Orwell used agricultural allegory to warn against the horrors of totalitarianism in Animal Farm. The modern Republican Party has used the family farm to justify estate tax repeal.

The farm as a political image is ancient and universal around the globe. Obama should task the metaphor to the salesmanship of renewable energy to the American people. American farms, whether they produce megawatts or fruits and vegetables, require public sponsorship to prosper. Obama, the self-proclaimed “skinny kid with a funny name,” won the White House with symbolism at his service. Like liberal linguist George Lakoff, he knows that political metaphors can become self-fulfilling prophecies.