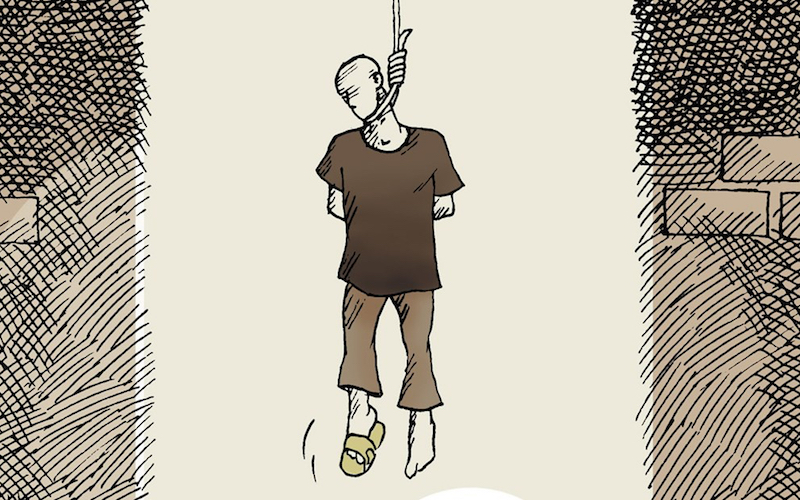

Iran: Children of Death Row

Iran leads as the world’s largest user of the death penalty and tops any country in the execution of offenders under 18. In the first half of 2015 alone, Iran executed nearly 700 young offenders. This is the highest it’s been in the last 25 years. So while more countries reject capital punishment, Iran continues to sentence girls as young as nine and boys aged 15 to death. A disturbing new report by Amnesty International has revealed state sanctioned execution of 73 offenders under 18 between 2005 and 2015 and at least 160 young Iranians are currently awaiting execution. Iran finds plenty of company with countries like China, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and United States that carry out the largest number of executions in the world.

The report reveals the litany of minor offenses that the state sees as worthy of ending a child’s life. Like Janat Mir, from Afghanistan, who was arrested for drug offenses after his friend’s house, where he was staying, was raided. Mir did not have access to a lawyer or consular services. He was believed to be 14 or 15 when he was executed in 2014.

The report is a distressing read, revealing the troubling accounts of scores of youths who are languishing on death row. Amnesty found that many of those awaiting execution can spend seven years in prison before they are hanged, and there are some who have already spent more than a decade on death row.

In most cases these young offenders are accused of murder, rape or drug-related offenses, which the Iranian government considers among the “most serious” crimes.

And yet Iran often denies confining young offenders to the gallows to die. Public statements by successive Iranian governments and parliaments have refuted that they execute children by drawing attention to the age of the offender at the time of execution, despite the fact that under international human rights law, it is the age of the offender at the time of the crime and not when they are at trial or at the time of sentencing. The blatant disregard of its human rights obligation is embedded in the judicial system: In April 2014, the Head of the Judiciary, Ayatollah Sadeq Amoli Larijani, stated: “In the Islamic Republic of Iran, we have no execution of people under the age of 18.”

Iran ratified the United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which it has consistently failed to abide by. The government is legally obligated to treat all those under 18 as a child. The CRC prohibits capital punishment and life imprisonment without the possibility of parole for children under 18. Criminal responsibility, the age at which children are deemed to have the capacity to infringe penal law should not be below 12 as set by CRC.

Iran has been under pressure by the U.N to stop using the death sentence for young offenders. In 2014, U.N. human rights chief, Navi Pillay, put pressure on Iran to stop the execution of a child bride who killed her husband after years of domestic abuse. Pillay asserted: “The imminent execution of Razieh Ebrahimi has once again brought into stark focus the unacceptable use of the death penalty against juvenile offenders in Iran…Regardless of the circumstances of the crime, the execution of juvenile offenders is clearly prohibited by international human rights law.”

Changes to the country’s Islamic Penal Code in 2013, granted judges the power to reduce death sentences for young offenders to a lesser sentence depending on the offender’s mental capacity and maturity at the time. In further signs of progress, Iran’s Supreme Court announced that youths sentenced to death could apply for a retrial under Article 91. Important as these reforms are, they do not go far enough. The problem, Amnesty finds, is that many of the incarcerated children are not aware of their right to retrial. The burden on children to prove their innocence had tragic consequences for Samad Zahabi, who was executed on 5 October 2015 without knowing he had a right to retrial. His life could have been saved. So far, retrials have been so cursory that such piece-meal efforts have not resulted in any significant practical change.

Special rapporteur for human rights in Iran, Ahmed Shaheed, said the nuclear deal and lifting of economic sanctions “can potentially have a beneficial multiplier effect on the human rights situation in the country.” If Iran desires to fully re-engage with countries politically and economically that also means addressing its obligations to protect children under international law. As Amnesty’s report clearly demonstrates, Iran must ensure that the full gamut of special juvenile justice protections under the CRC applies to every child.

Scores of children are living out their childhood on death row. It is legally and morally reprehensible that a state puts hundreds of children on death row before they have ever had the chance to reach adulthood. As economic opportunities widen for Iran, Europe, the US and other trading countries will need to call upon Iran to make more meaningful reforms to ensure their obligations under international law are being fulfilled, especially the right to life guaranteed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. If diplomatic circles in Washington and Tehran see 2016 as a new dawn for the country, its human rights record will remain a highlight of concern among the human rights groups and the international community until capital punishment for every child is abolished, completely and irrevocably.