The Prosecutor vs. Omar al-Bashir

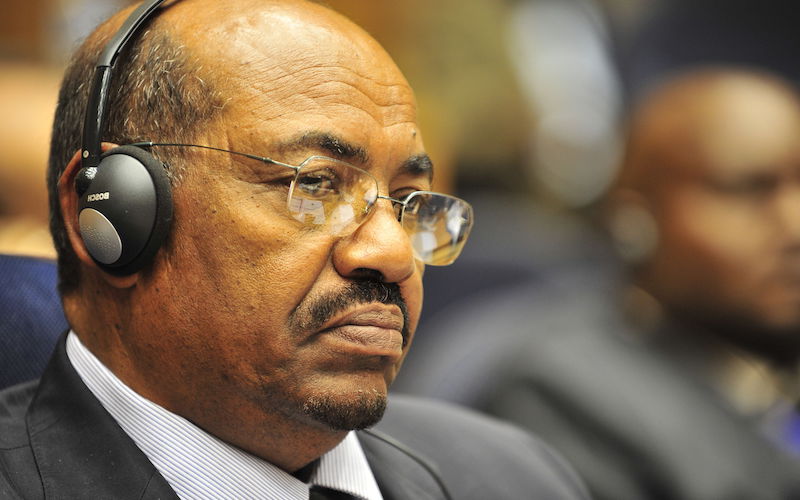

The atrocities perpetrated by the Government of Sudan (GoS) and the Janjaweed militia during the post-2003 Darfuri conflict constituted the first internationally condemned and acknowledged genocide of the twenty-first century. With the indictment of incumbent Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, the International Criminal Court (ICC) not only addressed the humanitarian crisis in Darfur but also challenged international immunity for heads of state. This indictment marked the first time that a sitting president of a state has ever been indicted by the ICC. In September, 2016, Amnesty International accused GoS of using lethal chemical weapons in Darfur against civilians, marking a new level of brutality on the part of the government and making the arrest of Omar al-Bashir even more important to the international community.

The conflict has a profound historical background. Violence had begun between the so-called “Arab” and “African” groups decades ago owing to competition for land and water resources, “Arab supremacism” in the region, and GoS’s biased policy against “African” ethnicity. Although the conflict occurred strictly along the dichotomy of ethnicities, in reality, Africans and Arabs are not distinguishable by skin color.

The current phase of the conflict in Darfur formally started in 2003 after the rebel groups, namely the Sudanese Liberation Movement and the Justice and Equality Movement, launched an attack on the airport at El Fasher. In response to this attack, the GoS equipped the militia Janjaweed and deployed it as a de facto expeditionary force to suppress the rebel movement. Systematic killings supported by a scorched earth policy were conducted in thousands of Darfur villages. The extent of the brutality was considered unprecedented in modern Sudan because males, including infants, were indiscriminately slaughtered; women were raped, mutilated, and murdered; and goods were looted and destroyed. Villages were continuously attacked even if they had previously been victims of violence.

On March 31, 2005, by a vote of 11 in favor and 0 against with 4 abstentions (the United States, China, Brazil, and Algeria), the Security Council referred the situation of Darfur to the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor under Resolution 1593. On March 4, 2009, the ICC indicted Omar al-Bashir, the incumbent president of Sudan, on two counts of war crimes (involving pillaging and intentionally directing attacks against civilians) and five counts of crimes against humanity (including murder, extermination, forcible transfer, torture, and rape) after reviewing the Prosecution Application submitted by Luis Moreno Ocampo. The Court later added the charge of genocide to al-Bashir’s warrant after the prosecutor appealed the decision.

Al-Bashir’s indictment has generated debate on whether the ICC can legally indict a current head of state who belongs to a nation that has not signed the Rome Statue, the founding treaty of the ICC. Advocates supported ICC’s decision to reject the doctrine of state immunity, which derives from traditional state practices and ensures that certain state officials can govern without improper foreign interference. Other legal scholars argue, however, that although justice should occur, the ICC lacks the legal justification needed to indict al-Bashir or ask for the assistance of other states to arrest him.

The international community has had a mixed reaction to the Court’s decision. Shortly after the ICC issued the second arrest warrant, the GoS expelled numerous international nongovernmental organizations from Sudan, which led to the deportation of more than 50% of the humanitarian aid workers stationed in Darfur. Furthermore, the GoS criticized the ICC as a neocolonialist tool applied by stronger states against Sudan. For his part, al-Bashir has repeatedly denied his commission of the serious crimes for which he was indicted. The GoS has additionally secured support for its opposition to the ICC’s arrest warrant from many African and Arab states. The African Union (AU) considers the ICC’s decision counterproductive to the well-being of the Darfuri people and has serious doubts regarding the court’s ability to conduct a thorough and unbiased prosecution. As of 2016, there have been eight cases of non-compliance with the ICC’s request for al-Bashir’s arrest; Chad (twice), Kenya, Malawi, Djibouti, Nigeria, the DRC, and South Africa have all acted directly against the indictment. Al-Bashir was invited to and visited each of these countries, thereby defying the ICC’s arrest warrant.

Each of these states is a member of the AU and has thus deferred to the ICC informed the Security Council and the ICC’s Assembly of State Parties of the failures of each of these respective states and urged the Security Council to take appropriate actions against them. However, these two institutions’ investigations merely resulted in the collection of the explanations offered by the aforementioned states.

Across the globe, the United States—a permanent member of the UN Security Council—vowed to uphold the ICC’s arrest warrant, and senior government officials expressed the importance of holding Darfuri war crime perpetrators accountable. China, however—also a permanent member of the Security Council—demonstrated marked indifference to the ICC’s arrest warrant by giving a state reception to Omar al-Bashir in 2011 and inviting him to a military parade ceremony in 2015. Russia and China have additionally been supplying arms to the GoS since 2004. France and the United Kingdom have expressed both support for the indictment and concern regarding the potential negative influence of the arrest warrant and removal of al-Bashir on the Darfur peace process.

Concerns over the fragile and precarious peace that was concluded between Sudan and South Sudan, which gained independence in 2011, have played a critical role in the ineffectiveness of the warrant’s enforcement. Although a successful referendum occurred in 2011, UN members remain worried that the removal of al-Bashir may provoke a war between Sudan and South Sudan, and that the resulting government’s ability to rule may be compromised. Sudan’s consent regarding the deployment of UNAMID (African Union/United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur) forces, a peace-keeping commission jointly established by the UN and AU, also remains vital in the UNSC’s considerations. Additionally, the relevance of Sudan’s attitude toward the delivery of much-needed humanitarian aid has caused other supporters of the ICC, most prominently the European Union, to avoid adding excessive political pressure that may directly endanger the people who live in Darfur.

The lack of enforcement of al-Bashir’s arrest warrant is detrimental to both the vulnerable persons who live in Darfur and international criminal justice. Unlike the cases of Slobodan Milošević and Charles Taylor, who were arrested after they were stripped of power, al-Bashir’s status as a current head of state provides additional challenges for the ICC. The ICC must consider alternatives which would prompt states to cooperate or extend the mandate to create a peace-keeping force that is focused on arresting al-Bashir. On the other hand, the current humanitarian crisis in Darfur appears to be not high on the priority list of the great powers of the world. As the world focuses on Assad’s abusive offensive and his deployment of chemical weapons in Syria, why do human right violations in Darfur somehow go unaddressed? It is time for the leadership of the P5 to adjust their policies toward Darfur and stop the GoS from abusing Darfuri people with conventional or chemical warfare.