Politics

Dismantling GOP’s “Conservative Expert-Interventionist” Hypothesis

Presidential hopefuls are nearly universally mocked for their non-committal prior to their official announcements. Stephen Colbert, famed for his tongue-in-cheek runs for the White House in 2008 and 2012, began his first campaign with the firm declaration that “I, Stephen Colbert, am officially announcing, that I am officially considering whether or not I will announce that I am running for President of the United States.”

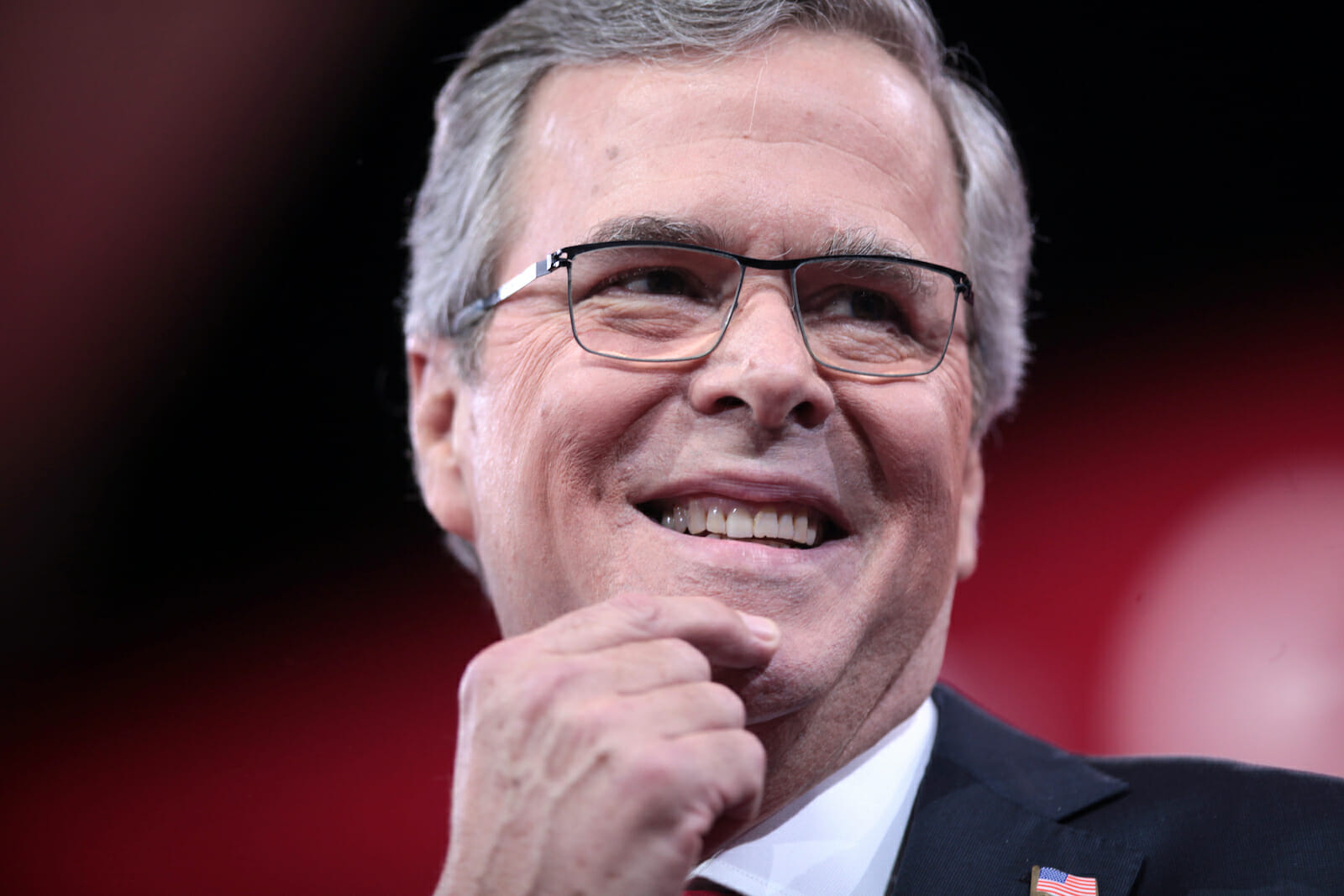

Indeed, this coyness seems to follow 2016 contenders like a shadow. Former Florida Governor Jeb Bush recently stated, “we need to have a candidate to lift our spirits” when side-stepping questions of his own candidacy, while Mike Huckabee responded to questions about a potential presidential bid with an “I’m keeping the door open.” Apparently, though, no one informed Congressman Peter King (R-NY) about the requisite amount of modesty and faux-indecision needed to run for President.

Appearing on Wolf Blitzer recently, King, after admitting plans to return to the nation’s first-primary state of New Hampshire in the near future, confided that he had told former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to “get ready” for a potential head-to-head matchup.

It’s not the first time that King has been upfront of his inclination to seek the Republican nomination in 2016, having stated “right now, I’m running for President” last year.

Such talk may seem remarkably candid from a politician, but it stems from a posturing that many that view themselves in the hawkish-wing of the GOP like King see as a noble and necessary cause in order to reassert themselves in a changing party.

“I see people like Rand Paul and Ted Cruz, and to me, I don’t want the Republican Party going in that direction,” he recently declared. “Whether it’s me or someone else, I want to do all that I can to make sure that what I call the ‘realistic foreign policy wing’ and ‘national security wing’ of the Republican Party does not give in to the isolationists.”

The imagery of the “national security” wing of the party versus the newly-emerging “isolationists,” led by Paul, Cruz and many Tea Party members of the House Republican Caucus, has been a compelling narrative for the political conscious of Washington. However, the representation of this internal debate within Republican and Conservative circles has often been portrayed as idealistic or naive newcomers, flanked by strong support from an excited base, up against experienced veterans of foreign policy speaking for the Party’s national security experts.

With this worldview, King and other hawkish Republicans like John McCain and Lindsay Graham have often spoken with the presumption of those who believe themselves to be the defenders of a legitimate consensus by scholars of policy in favor of American geopolitical leadership in the world. Writing in an op-ed for the New York Times, McCain recently lamented the “disturbing lack of realism that has characterized our foreign policy,” while urging for stronger responses to Russia’s aggressive posturing towards Ukraine.

The central thesis of King, McCain and other GOP hawks is simple: while there may be a political debate within the GOP regarding the efficacy of U.S. global leadership, a legitimate policy debate within Conservative thought there is not. This conception of the “expert-interventionist” link underpins much of the national security ethos many Republicans have been echoing in recent times.

However, a challenging proposition for this thesis is the extent to which the foreign policy soul-searching within the Republican Party these days extends beyond the base to encompass the Right’s thinkers and scholars as well. This has been particularly demonstrated by the on-going crisis in Ukraine. A recent survey of academics that study and teach International Relations conducted by the Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP) Project at the College of William & Mary finds overwhelming opposition to activist U.S. foreign policy. More problematic for the “expert-interventionist” belief of many Republicans, though, is the profound division – and sometimes restrained policy views – of even those academics and scholars who self-identify as Conservatives.

John McCain has been unequivocal of the necessity to send armed supplies to the Ukrainian government. By a 43%-46% margin, though, experts who identify themselves as fiscal Conservatives opposed the sending of military aid to Ukraine in their on-going battle with Russian separatists in eastern provinces (those who identified as social Conservatives, asked as a separate question, narrowly approved of military aid by a 46%-42% margin.)

While these results are hardly a rallying call for neo-isolationism by Conservative academics and intellectuals, Conservative scholars were more likely than Liberal ones to call for aid to Ukraine, it nonetheless challenges the assumption that the Right’s thinkers are lock-step behind the Republican Party’s hawks. If the “national security wing” is what Peter King claims to represent, surely this wing ought to include those who professionally study and research national security.

Indeed, even The Heritage Foundation, the traditionally interventionist think tank, has expressed caution in terms of action in Ukraine, advocating for strengthening defense for other NATO members and sending military aid to Kiev, only with strong oversight and restraint. Further, while there may be disagreement over military aid to Ukraine, amongst Conservative scholars surveyed by TRIP there was strong consensus against further intervention: 68% of fiscal Conservatives (and 61% of social Conservative) opposed sending NATO ground forces if requested by Ukraine and 47% of fiscal Conservatives (and 38% of social) categorically opposed extending a NATO membership plan to Ukraine under any circumstances within the next decade (and fewer than 30% supported an expedited plan for membership in the near-future.)

The importance of the opinion of these academics is two-fold. First, they present a riposte to the GOP’s hawks from similar ideological perspectives. While pundits (particularly on the Right) have often pointed to a liberal bias and control within academia as a reason to dismiss scholars’ input, strong pushback from even Conservative thinkers is particularly problematic for Republican National Security policy.

For example, a rather wide-spread argument by many Republicans over the past few months has been the implications for broader incursions by America’s enemies as a result of dithering on Ukraine and elsewhere. Consequently, individuals such as former Vice President Dick Cheney have warned that a lack of intervention by the United States has displayed low levels of resolve that foreign leaders such as Putin will take advantage of.

However, when asked “does the United States need to demonstrate its willingness to use offensive military power in Ukraine in order to show U.S. rivals that it is resolved on other issues and in other regions,” 75% of Conservative professors and academics in the TRIP survey (with little variation between social and fiscal Conservatives) disagreed with the assessment.

Further, asked specifically whether U.S. diplomatic involvement in Ukraine, Syria and Iran has weakened the ability for America to broker a Middle East peace deal, Right-leaning academics disagreed, with 67% of social and 73% of fiscal Conservatives unwilling to support the position. Ultimately, Republican and GOP-leaning academics’ fierce opposition to many traditionally hawkish views espoused recently by those such as McCain, King and Cheney, is indicative of a false-consensus employed by those in the “realistic foreign policy wing” that King describes.

Secondly, though, the views of these scholars are important for the broader implications they demonstrate of internal divisions within the Republican Party. Rather than being a division stemming from upstart newcomers and an isolationist-twinge in the GOP base, the debate between the interventionist foreign policy that Republicans since Reagan have traditionally been known for and practices of restraint in foreign affairs permeates throughout the Party.

As the narrative for 2016 begins to play out, no doubt individuals who have often been associated with a more active foreign policy such as King will attempt to paint their less interventionist colleagues as ill-informed and out of sync with mainstream policy experts. This interpretation, however, of where the opinions of international relations experts, particularly Conservatives ones, lie is empirically unsubstantiated from the responses gathered from the TRIP data.

While it is undoubtedly true that the Republican Party has entered a period of internal soul-searching for a cohesive foreign policy doctrine, as advocates for greater and less American involvement across the world have their say, it is also true that this division extends beyond the political realm and into the policy realm as well. What this ultimately means is that the gap between hawks and doves, as it were, will not be bridged or ended simply by a political victory by one side. The recent string of primary victories of supposedly “establishment” Republicans over Tea Party insurgents may represent short-term gains by interventionist GOPers, but so long as thinkers and scholars also remain divided – and indeed tilted against activist foreign policy – Conservative leaders will need to deal with the impacts of a divided intellectual front.

In many ways, the Democratic Party has been plagued by a similar problem since assuming power in Washington in 2009. Despite a president and Congressional leadership comfortable with the exercise of the use of force, the lack of certainty over whether an authorization of military action in Syria would fare well with House or Senate Democrats, for example, stemmed from a pacifist-base coupled with a large swath of the intellectual Left weary of foreign intervention. Individuals such as Harvard Professor of International Relations Stephen Walt penned letters to Congressmen advising against a strike at the Assad regime. However, unlike the Republican establishment, one would find it difficult to see Democrats actively berating opponents of action in Syria as ignorant of national security, or as out of sync with mainstream policy experts.

Likewise, it may very well be the case that the Republican Party that emerges in the 2014 midterms and beyond will, much like the Democrats, have to accept the coexistence of interventionist and non-interventionist factions. Indeed, the Democratic Party seems to have endured with a pluralist take on national security through the presence of a libertarian-leaning base opposed to an expansive foreign policy buttressed by the views of prominent scholars and thinkers. Contrary to the adherents of the “expert-interventionist” view of hawks such as King, McCain and others, the latter case of the Democratic Party seems to hold true for the Republicans as well, even if to a lesser degree.

Though professors and academics do not shape foreign policy in their own right, the combination of individuals they train, the consultancy to think-tanks and policy makers many contribute, the positions in government some occupy on occasion, the research regarding international relations they produce, and the representation of thinkers and opinion-makers they comprise, form some sizeable impact on the discourse of domestic politics. Data collected from the TRIP survey of academics demonstrates strong levels of incredulity by Conservative scholars of foreign affairs regarding additional intervention by the United States abroad.

As the Republican Party continues internal debates both publicly and privately regarding the future direction of the party’s foreign policy, the rejection of the “expert-interventionist” hypothesis that seems to have dogged political and media thought regarding Conservative policy is necessary to achieve a more realistic understanding of the contemporary divide within the Party and the potential for coexistence of the viewpoints moving forward.