Tech

The CIA Helped Win the Space Race

Recently declassified documents from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) present a clearer picture of the all-encompassing and wide reaching efforts to win the Cold War’s Space Race. George Washington University’s National Security Archive, a repository of declassified U.S. documents described as the world’s largest nongovernmental collection, unveiled a new batch of once highly sensitive CIA documents in a release titled, “Soldiers, Spies and the Moon: Secret U.S. and Soviet Plans from the 1950s and 1960s.”

The newly released cache of formerly classified reports focuses on a series of military initiatives, as well as covert and surreptitious efforts to advance America’s lunar programs.

During the 1960s, following President John F. Kennedy’s iconic May 25, 1961 address to Congress in which he set the goal of putting a man on the Moon within the decade, the Cold War was reaching epic proportions. President Kennedy’s speech served to throw the gauntlet by setting the terms and singling out the ultimate prize for the soon to be gargantuan and nationally ambitious Space Race – a successful manned mission to the Moon.

Seizing a Soviet space craft

During an unspecified year, the declassified CIA document titled “The Kidnapping Of the Lunik,” from the Winter of 1967, notes that the Soviet Union embarked upon a worldwide tour of multiple countries to show off and amaze foreign nations with exhibits designed to personify the Soviet Union’s economic, industrial and scientific achievements.

As part of the effort, the Soviets included what was initially assumed to be generic mock-ups of their successful space vehicles such as the Sputnik, and the Lunik, respectively, the first successfully launched satellite and the first man-made object to reach the Moon. The Lunik was also the first to send photographs of the Moon’s far side, which was never before seen from Earth.

As the CIA paper explains, when the exhibition came to the U.S., American intelligence officials realized that there was a slim possibility some valuable technological insights could be gleaned if there were an opportunity to investigate the Lunik vehicle should surreptitious access be afforded.

Initial excitement over the possibility of securing Soviet technology and space vehicle design details was soon tempered, as American intelligence officials doubted the Soviets would send production value examples to tour the public, especially on U.S. soil. Indeed, many intelligence officials assumed that any Soviet exhibition, including space technologies and vehicles, would unquestionably not be the real McCoy.

“It was presumably a mock-up made especially for the exhibition; the Soviets would not be so foolish as to expose a real production item of such advanced equipment to the prying eyes of imperialist intelligence,” notes the CIA.

Before adding, “Or would they?”

A clandestine visit with the Lunik

Like something out of a Robert Ludlum or Tom Clancy spy-novel, it was soon decided that whether or not the Lunik exhibit visiting America was real or even partially real, it was necessary to determine if it had any intelligence value. American intelligence officials, in turn, decided a look was worth the risk.

Following the exhibition’s closure at an unspecified U.S. location, intelligence officers were able to secure 24-hours of uninterrupted access to the Lunik.

It wasn’t long before these intelligence officers determined that the Lunik model in question was an actual “production item” that had been scaled down to a degree with some precautions made by the Soviets, since the “engine and most of the electrical and electronic components had been removed.”

Even so, there was much to be gained and as the CIA notes, “A few REDACTED, had been copied from the Lunik during the operation, but not with sufficient detail or precision to permit a definitive identification of the producer or determination of the REDACTED system used. It was therefore decided to try to get another access for a factory REDACTED team.”

The decision was made and the plans by the CIA to somehow figure out a way to “borrow” the Lunik while it was in transport from one city to the next was put into motion.

In a section of the declassified report appropriately titled ‘Lunik on loan,’ the CIA proceeds to explain how its team set out to secure some extended quality time with the Lunik, away from the prying, and most undoubtedly disapproving, Soviet minders’ eyes.

What transpired next will go down in Cold War espionage-lore.

The ‘borrowing’ of the Lunik

There were two basic options to secure a more in-depth review of the traveling Lunik: intercept it while in transit on a truck or after it was delivered to a railway station for overnight holding before departing to the next exhibition city. The initial preference was to gain access when it was on the rail haul, but after a thorough examination it was determined that such an approach was simply not feasible.

With opportunities limited, the CIA decided to intercept the vehicle transporting the Lunik craft from the exhibition to the rail haul destination. In turn, American intelligence officers were able to delay the Lunik transport from leaving the exhibition and ensured that it was on the last transport vehicle to leave.

This delay enabled intelligence officers to tail the transport vehicle and thereby determine if Soviet agents were keeping a watchful eye on the Lunik during its transit. As it turns out, no Soviets appeared to be escorting the Lunik.

At this point, the CIA made the decision to intercept the shipment by forcing the driver to pull over. Soon afterwards, the driver of the truck was replaced and sent to a nearby hotel for the night while the container housing the Lunik was removed and relocated to a near-by salvage yard, previously arranged just for the mission.

With painstaking exactitude and technical exploitation, CIA officers worked through the night to gain access to the Lunik interior to garner all the necessary information they could whilst ensuring that no telltale signs of surreptitious entry were left behind.

As the declassified report states, “The nose and engine compartments were double-checked to make sure no telltale materials such as matches, pencils, or scraps of paper had been left inside.”

By 4:00 am U.S. intelligence officers were finished with their work and by 5:00 am the Lunik, nestled comfortably inside its transport container, was reloaded onto the delivery truck. The original driver was placed inside and told to proceed to the railway station to deliver the crate.

At 7:00am, the Soviet who was responsible for inventorying exhibition items arrived at the railway station only to find the transport vehicle holding the Lunik already there awaiting him. Without suspecting anything was amiss, the Soviet noted the crates’ arrival and saw it loaded onto the railway car – never giving the slightest hint of something out of the ordinary.

As the CIA’s report concludes, “In due course the train left. To this day there has been no indication the Soviets ever discovered that the Lunik was borrowed for a night.”

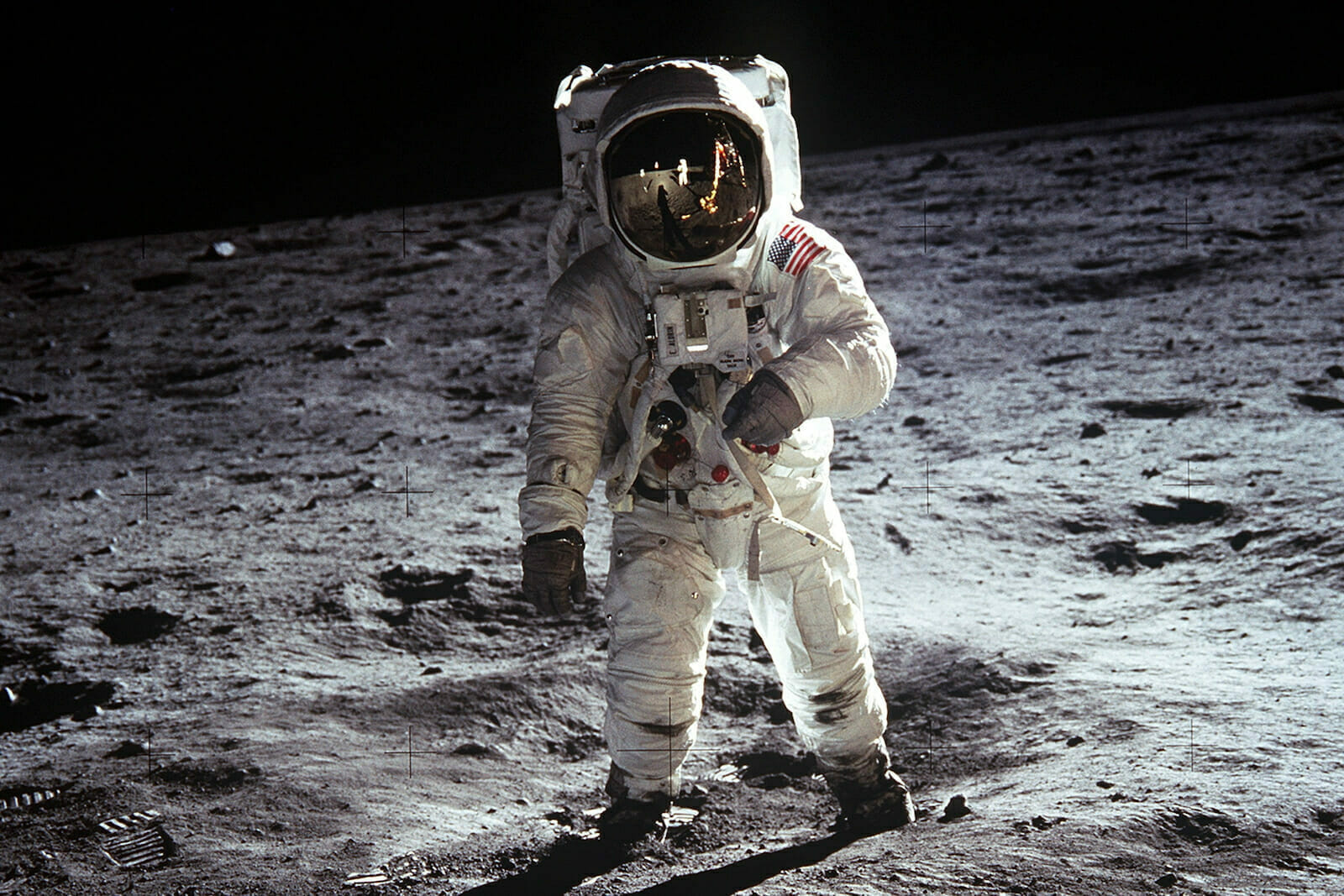

One small step

The CIA managed to successfully secure access to the Lunik twice, kidnapped (or “borrowed”) it once, and photographed vitally sensitive information from “a Soviet upper-stage space vehicle” while returning it, all before the Soviets expected a thing.

One can only imagine that when astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first man to set foot on the moon in 1969 and famously called it, “one small step,” that a select and rightfully proud bunch of CIA officers smiled wide knowing that they had been a part of the many ‘small steps’ required to achieve America’s—and the world’s—first successful manned mission to the Moon.