‘Ex Machina,’ a Review

Why are movies about androids/cyborgs/creatures of artificial intelligence so engaging? Presumably because they cause you to wonder about the very nature of human intelligence. Nature vs. nurture. You wonder if you will be drawn into the personas of the AIs in question. The fascinating creature whose skin conceals whirring gears and green motherboards- is it a metaphor or is it “real”? Live or Memorex? Does it have inherent traits such as sexuality? Can it feel?

As an ardent fan of the film Blade Runner (1982) and the first two Terminators (1984 and 1991), I looked forward to viewing Ex Machina (2015) with just those questions in mind. The charming young guy who sold me popcorn told me that Ex Machina was a wonderful film and that I would like it. He said “It’s…provocative!” He was quite right.

When you check the definition of “deus/a ex machina” you find that it indicates “a person or thing (as in fiction or drama) that appears or is introduced suddenly and unexpectedly and provides a contrived solution to an apparently insoluble difficulty.” In the case of this movie, the person or thing that is introduced suddenly is the alternate personality of the android Ava. The sudden revelation of power- whether of masculine strength or feminine wiles, or both – which allows the protagonist to break out of her bonds. It is striking and unexpected –and engaging.

And indeed, Ex Machina is powerfully engaging. As with its precursors Blade Runner and Terminator (1, 2 and 3) the AIs (androids, replicants) steal the scenes from the humans who interact with them.

They have both traditional masculine and feminine traits – they are physically beautiful, capable of physical and technical feats beyond those of their inventors or human counterparts. They can tear up the night! dancing like fiends in perfect synchrony along with their creators. They teeter perilously but invisibly on the borderline between human and robot.

The Ex Machina androids are far more interesting than their human creators or antagonists. The Ex Machina humans, soon to be cannon fodder, do not draw the gaze: a geeky naïve but arrogant young programmer and a crazed belligerent hard drinking cyberworld giant, who pouts, bellows, screams.. and, behaves like a cruel abusive parent towards his female android creations. The young programmer is a true geek- manipulated into believing he has won a contest or exhibited superior programming skills or, finally, as he accurately understands it, chosen for his browser history – his pure pitiful human isolation and neediness — to perform a Turing test on an AI to determine if she meets the criteria for “intelligence.” In the end the humans’ level of intelligence or testosterone doesn’t matter- both are doomed.

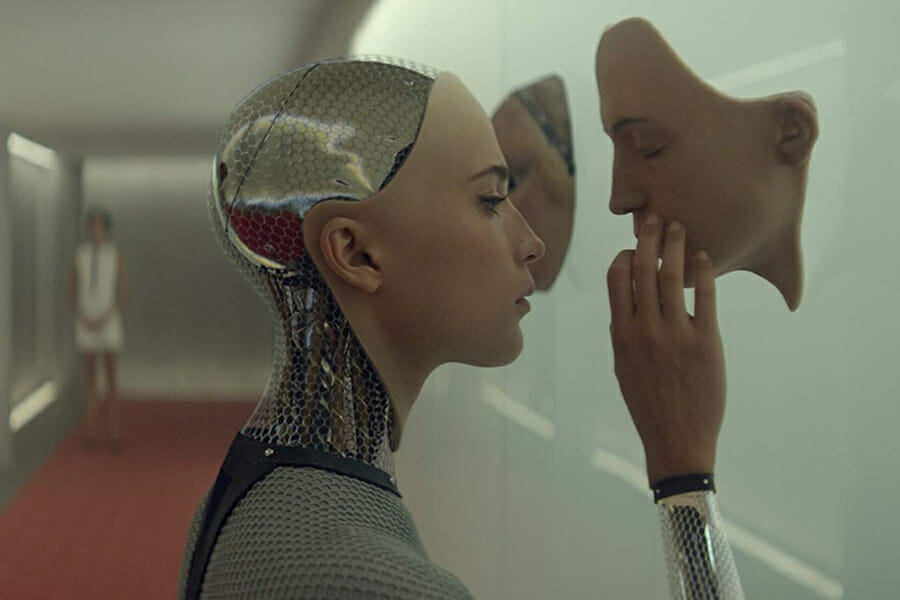

And so you find yourself ticking off on fingers the characteristics of these movie creations– human or android? Are they the superior race? How do they differ from humans? Can they argue? Question? think, deduce? Manipulate heavy machinery? Do they have sexuality? The super programmer, dangling Ava before the young programmer, says that she has pleasure sensors and can have sex. (Implied – he is welcome to try to win her.). The exquisite yet sinewy AI Ava whose gorgeous exoskeleton when hid with human clothing still peeps out from her neck – causing powerful urgent reactions in the young geek who peeps at her– can also cause power failures in her environment at will.

There is usually little question about the traits of male androids/cyborgs. Although there are none in Ex Machina like their Terminator precursors, the Arnolds of the android world, are creatures whose very bodies are heavy armor and weapons of war.

At the same time, Terminator male androids or cyborgs may also exhibit a strange kind of “feminine” affection for their humans. The Terminator of T2 appears to care for the young male human hero, future savior of the human race. But the Terminator‘s are a franchise. In these movies, for the creature who is sent to serve and protect the savior, there are many more monstrous cyborgs sent to kill him.

In Ex Machina, the female androids—whom we learn are multiple copies of a single constantly altered mind jelly with gleaming interior circuitry enveloped in changing physical human-like sleeves– we are ranging onto more subtle and dangerous ground. Are these androids the lovely innocent creatures they appear to be? Or do they have…ulterior motives? do they secretly desire nothing else but to use their “feminine” wiles to escape their locked up lives, controlled by their male human creators, into the free world? Can they conceal their motives and flirt, tease, charm, manipulate their creators, into traps?

In short, can they deceive, hurt or kill their creators? of course, they can and do. It would hardly be a movie otherwise.

Think back to Blade Runner. Four androids – one male, three females–are the centerpieces. They are beautiful creatures; seductive pleasure givers; they also have great physical strength; but are ultimately vulnerable.. They are also potentially destructive of anyone in their way as they work to gain freedom from human bondage. With limited self knowledge and ability to plan and control their destinies, however, they are all ultimately vulnerable to their internal off switches.

It’s hard to forget the terror of the tall and gorgeous character played by Darryl Hannah in futuristic LA, hiding like a street person and bursting out of a pile of garbage bags when surprised by her drab but kindly little geriatric creator, yet once safe and in hiding again, dancing and flirting, cruelly mocking him.

The male android Roy, played by Rutger Hauer, a breathtakingly beautiful creature himself, appears far more sophisticated. But he too is vulnerable. He falters and fails, killed by his unalterable off switch. In Hauer’s death scene which lingers long in the memory, he sits like a gargoyle on a rooftop in the rain, folds his arms/wings, bows his head, and slowly turns off and dies.

Unlike her fellows, Sean, the central female android character in Blade Runner falls in love with Decker, the seedy private eye played by Harrison Ford. She believes she is truly human, fed by false memory implants which detail an unreal childhood. Once she is convinced of their falsity she nearly breaks apart. In a speedy transition she transfers her “human” feelings onto Harrison Ford. By hitching her wagon to his star she may temporarily escape her own off switch. As the character played by Edward James Olmos says, “She may not live long! But then who does?”

The Ex Machina Ava, on the other hand, has a lot of latent power. She is a goddess, a “dea” who appears innocent but can manipulate other creatures, keeping them dancing on her strings. She is also a tough survivor.

At first it’s hard to believe that such a gentle seeming creature could be dangerous. Ava and her fellow female androids readily play the ultra feminine geisha. They sing, dance, serve food, put together a peep show — putting on human clothing and then taking it off, under the human male gaze.. They can supply sex on demand and so we’re told, even enjoy it. Ava is even a modest creator herself- she can draw pictures of her surroundings.

But Ava lulls both her creator and her would be savior into a false sense of security. Like her earlier model android sisters – whom we see hammering silently and madly against a translucent plastic wall, crying “Let me OUT!” she has both the blunt physical strength to master her situation and the subtle intelligence to carry it off. She is a deviser of plots, a manipulator of the naïve young programmer and her creator alike. She kills one man – whose only defense is to yell “Ava! Go to your room!” like a demented parent.. and maroons the other in the bunker, forever. When last seen Ava has ditched her naked half human half machine persona and is clad in a virginal white lacey dress, hair down and flowing. She has exited the bunker. A helicopter sent to pick up the young programmer picks her up instead and takes her back to the mainland.

Ava has left at least three bodies in her wake. A goddess and a machine alike, by her own efforts she is free. She has resolved the dilemma. She is both the actor and the act of divine intervention. Presumably, she will find a way to live in the human world.

The audience for this film sat silently, stunned, at the end, reluctant to break the spell and leave.