Business

Our 200-year-old Obsession with Productivity

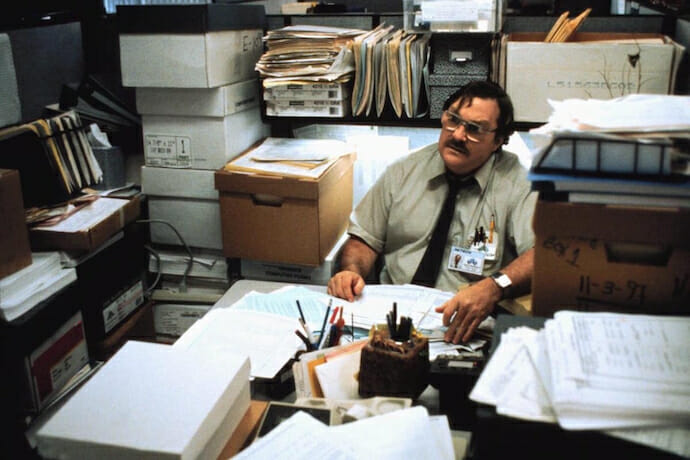

The quest for achieving peak productivity is now akin to a religion, one consisting of high priests (time management gurus, life hack specialists, productivity coaches, headlining management professionals), various teachings (apps, tools, approaches, methods, reminders, workstation re-designs, forms of discipline), and millions of willing aspirants (early adopters, workshop participants, testifiers, devotees). A search for “how to be more productive” yields, at present count, 40,900,000 results.

What remains deeply puzzling about our obsession with personal productivity is that it is a rather uninteresting goal. Isn’t peak productivity an oddly deflating cultural ideal, especially when put in comparison with Achilles’ heroic feats, Solon’s excellence in statecraft, St. Thomas Aquinas’s holiness, Beethoven’s beautiful symphonies, and G.I. Gurdjieff’s spiritual search? How did it become such an ideal for us to aspire to?

A more fundamental question than how we can “hack” our productivity is why we place so much importance on doing so in the first place.

First explanations can only take us so far. Some speak of being overwhelmed at work and of the desire to no longer feel overwhelmed. Others write of the “immense satisfaction” associated with “the act of crossing an item off a to-do list.” Still others refer to the lack of time coupled with the large number of demands placed upon them and hope, as a result of their becoming more productive, that they can have more time to do whatever it is they wish to do. Their assumption is that “time is a limited commodity,” a scarce resource that needs to be used with the utmost prudence.

These explanations can be reduced to two basic kinds. The first kind implies that much of life is burdened by mental suffering — feelings of being overwhelmed and stressed — that can, through our own concerted efforts, be alleviated or at least coped with by finding the right productivity hacks. The second suggests that life is a “middle class epic” whose finale would depict a form of satisfaction following from the completion of the most challenging tasks at work. Call it Inbox Zero Integrity.

Yet neither the desire to lessen our everyday mental suffering nor the pursuit for short-term satisfaction ultimately explains our deep cultural obsession with productivity. What drives it instead, I’d argue, is a 200-year-old movement toward making work the center of our lives.

Elon Musk and the Bourgeois Era

Ask enough people whom they admire most, and many, especially, but not just, those involved in the tech industry, will say, “Elon Musk.” What is admirable about him, they’ll say, is that he is a visionary entrepreneur. Why, it’s worth asking, would this be the first thought that comes to mind?

Because this is the Bourgeois Era and we’re all bourgeois now.

The “Bourgeois Era,” a term I borrow from the economic historian Deidre McCloskey, refers to an incremental, though massive, shift in worldview dating to around 1800. During this shift, the aristocratic and priestly classes fell out of favor while the merchant class, certainly for the first time in history at this scale, rose to the fore and, in so doing, had a large hand in setting the agenda for what a good life would look like in the modern world.

Suppose the Bourgeois Era were a four-act drama. It might look something like this:

Act 1: The Bourgeois Deal and Bourgeois Revaluation (Beginning in 1800)

This marks the beginning of the shift away from aristocratic and priestly values and toward merchant values. McCloskey argues in her book, Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World, that “trade tested betterment,” a newfound openness to anyone, regardless of class, status, or social standing, coming up with ideas that, tried and tested in the marketplace, aim at social improvement, caused a major shift in social life. Commerce became not simply tolerated by the merchant class, but sweet to more and more commoners; deals were made according, at its best, to the principle of fairness; ideas, practical creativity, and inventiveness all promoted human betterment; entrepreneurs, whether small town shop owners or major economic players, were held in high esteem; and the market became a gauge for testing whether a business idea could stand or fall. This shift McCloskey calls the “Bourgeois Deal.”

The key to the Bourgeois Deal, McCloskey shows, is the “Bourgeois Revaluation.” The pagan aristocratic virtues of honor and leisureliness and the Christian peasant virtues of charity and reverence were both supplanted by the bourgeois virtues of prudence, temperance, trustworthiness, and pride in fair dealing. Where the aristocrats lauded heroes and Christians venerated saints, we bourgeoisie honor the savvy dealer and, most of all, the visionary entrepreneur — once Steve Jobs and now Elon Musk. Because of the Bourgeois Revaluation, it’s now common sense to believe that we know ourselves and others once we know what we and others do for a living. Paradoxically both enterprising and modest, this new secular ethos eschewed war as well as the promise of salvation in favor of the peaceful relations and incremental social improvements made possible by trade in innovative products and services.

Act 2: The Golden Age of Trade-Tested Betterment (1945 to 1980)

As GDP grew after World War II, many middle-class Americans were able to own their own homes, to appreciate creaturely comforts and technological advances, to cleanly divide work life from home life and to retire. Seeing their parents live with affluence, Generations X and millenials came to believe that the future would be even brighter.

Act 3: The Work Society (1945 to Today)

After World War II, total work, a term coined by the German philosopher Josef Pieper, began slowly operating in the background to transform human beings into workers, more and more of life into work. While it’s true that the length of the workweek in the United States has been shortening since the end of the nineteenth century (from approximately 69 hours in 1830 to around 40 hours today), these numbers fail to reflect the qualitative way in which work has become central to our social identity. It is during this period, especially from 1980 to the present, that the Bourgeois Era overextends its own logic to the point at which life becomes burdensome, most especially for knowledge workers.

Act 4: AI and the Threat of Technological Unemployment (Our Potential Future)

With the arrival of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, we may be nearing the end of the Act 3, the result of which could be technological unemployment in the trucking industry, manufacturing, the service industry, and elsewhere. If this does come to pass, will we be facing what the futurist and historian Yuval Harari sees as the emergence of a “useless class”? It is Elon Musk no less who, insisting on the centrality of “meaningful work,” fears the threat of AI to ordinary people: “[The] much harder challenge is: How will people then have meaning? A lot of people derive meaning from their employment. If you’re not needed, what is the meaning? Do you feel useless?”

So What? To Begin with, the Void

I speak daily with individuals working in the tech industry, those whose “spiritual battle” is between falling prey to the “slot machine in their pockets” and implementing life hacks that will enable them to optimize their personal productivity. What I see is that we’ve taken the bourgeois virtue of hard work, or productivity, and applied it to ourselves with ruthless persistence.

But why? First, as progeny of the Bourgeois Revaluation, we, unlike aristocrats, have no wars to fight, honors to defend, courts to attend, leisurely hunts to go on, or liberal arts to pursue. Nor, unlike devout Christians of the medieval period, do we have inner spiritual struggles over which we can rend our souls. Rather, in the work society we have small betterments to make, tasks to complete, daily problems to solve, minor burdens to carry, modest marks to leave on the world before our time has come. Given this background, it makes some sense to throw ourselves into how we could improve on our bettering, especially our self-bettering.

Second, the work society actually requires productive bodies, and thus it uses us, somewhat akin to the way that natural selection does, to reproduce itself. Our self-

internalization of productivity, as Foucault noted with regard to self-discipline, is more effective than having it wrought upon us by others.

We adopt the illusion that personal productivity is itself the end of suffering, or is itself happiness, when in actuality, the aim of personal productivity is to enable the work-society to continue. Just as, according to Robert Wright in his book Why Buddhism is True, “Natural selection doesn’t ‘want us’ to be happy” but rather to “be productive, in its narrow sense of productive,” so the work society doesn’t want us to be happy but instead to be more productive in its sense of the term. The truth is that we are its tools.

Third, we have the voiceless void to avoid. As Michael Coren, a friend and writer at Quartz, wrote to me in an email, “I think the void is central. We are always seeking to fill something within us. That vacuum will suck in whatever carving our minds fixates on. In our society, perhaps, that means increasing productivity.” But which void is that exactly? It is “the Godshaped vacuum” of which Pascal once movingly wrote left by the collapse of a Christian metaphysic, one that unleashed nihilism into the modern world? The recovering lifehacker John Pavlus hints at this when he writes, “I think lifehacking is so seductive because it’s simply easier than asking some bigger, harder, more important questions about where your time and attention go.” Those bigger, harder questions are philosophical in nature: Who am I? Why am I here? What is life ultimately about? Is there stillness beyond hustling?

The work society, by promoting ceaseless busyness and ever-greater productivity, prevents us from even asking ourselves these questions.

So, What’s Been Lost?

Most importantly, along with Bourgeois Era’s rush toward peace and prosperity came the loss not of free time but of genuine leisure. As the late political philosopher Sebastian de Grazia, in his book Of Time, Work, and Leisure, aptly put it, “Leisure is the freedom from the necessity of occupation.” Leisure, he also notes, is not to be confused with spare or free time: the latter, which is a quantifiable form of rest, is the complement of work, a way of resting and “recharging one’s batteries” with the goal of being more productive whereas the former makes a radical departure both from free time and from work. How so?

To be obsessed with productivity gains is to be single-mindedly focused on the useful and the necessary. While these ought to play a role in the maintenance of our lives, there is much more to the story: in genuine leisure, which is set beyond the demands of the day, we’re able to experience the stillness, to apprehend the lineaments of reality.

Reevaluating the Bourgeois Revaluation

It’s time to revalue the Bourgeois Revaluation, which set the merchants’ values above those of all other classes. True, as the status of the merchant class rose and that of the warrior and priest classes fell, ceaseless activity and endless productivity have diminished our bellicose impulses, making us friendlier with strangers and more capable of extending social trust while bettering the lives of ordinary people who’ve grown accustomed to making no big deal out of others’ differing beliefs.

Still, the bourgeois values also came with their own vocabulary, which is now our own. Many of the work-saturated terms that govern our lives are, it turns out, only 200 years old, and all of them, not just the concept of personal productivity, are in need of examination and revaluation. Which of our ideas about work are causing us needless suffering? Must the chief aim of a formal education be gainful employment? Need the career be the central organizing concept of a good life? Must a week be divided into a “workweek” and “weekend,” much of life into “work” and “vacation”? Is a lack of productivity necessarily laziness? Is busyness really a badge of honor, not to mention too an unjustified form of pride? Is it true that we know ourselves and others when we know what we and they do, or is this instead a canard? And, not the least, were there some vital spiritual ideas — for instance, transcendence, sacredness, and neighborliness — lost when Christianity was largely forgotten, and are there some inspiriting aristocratic ideas such as courage, grace, and leisureliness that merit revisiting?

How might we live if there were more to life than what we’ve been led to believe?