A Sanction that Smarts

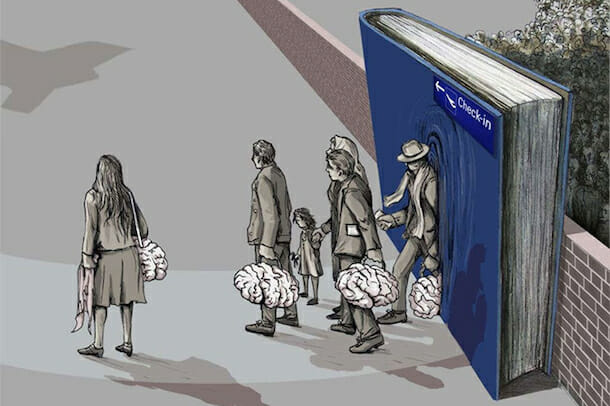

With Washington and Moscow engaged in a seemingly interminable game of tit-for-tat—volleying diplomatic expulsions and economic sanctions back and forth—the search is on in Washington for ways to impose true costs on Russia for its malign behavior abroad. The efficacy of the measures taken thus far remains debatable, yielding some tactical upsets at best, symbolic overtures at worst. To land a more strategically impactful blow, the U.S. should zero in on a long-exposed Achilles’ heel, and mount a concerted effort to accelerate Russia’s ongoing “brain drain.”

Already at a perilously low point, U.S.-Russia relations appear destined for tension for the foreseeable future—newly-appointed Secretary of State Mike Pompeo recently declared an end to the era of “soft” U.S. policy toward Moscow. However, while the State and Treasury Departments have been working overtime to provide the White House with levers to induce President Putin to alter his course of post-Soviet revanchism, the Department of Homeland Security could deploy from its arsenal a far more effective tool: a targeted expansion of student and work visas specifically targeted at Russian recipients in the STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields.

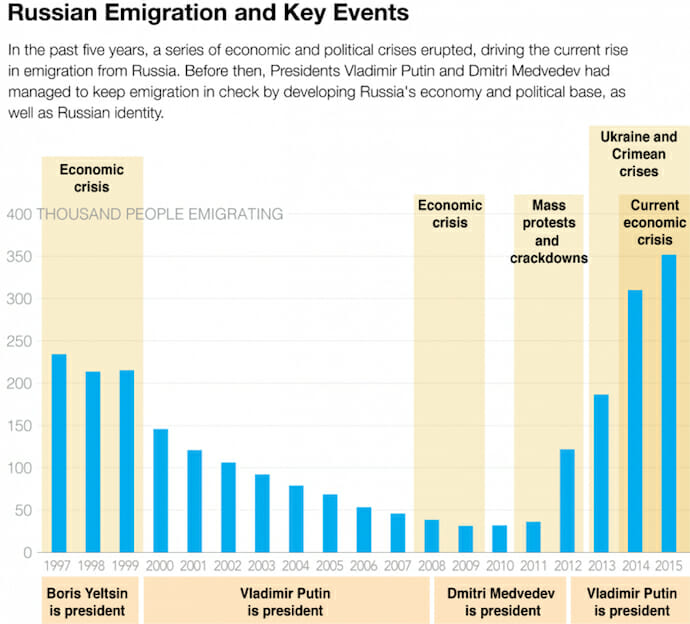

Over a hundred thousand people emigrate from Russia each year, most of whom are bound for the West. Roughly a third of them leave to pursue advanced degrees; an average of 40 percent are already highly-educated. Moreover, the leading factors behind their decision to leave Russia are economic and political. In other words, the Putin system appears to have overplayed its hand on high energy prices, while making home an inhospitable place to do business—leaving its human capital up for bids. Speaking at the Moscow Economic Forum last month, President of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAN) Aleksandr Sergeyev complained of a disconnect in how Moscow views “brain drain”: “We fear hemorrhaging dollars—every month counting how many go this way, how many that way. For some reason no one counts how much intellect flows out of the country.”

Shortly thereafter, RAN reported some alarming trends: from 2013 to 2016, the number of highly qualified specialists emigrating from Russia had doubled; while research and development cadres have diminished at a rate of 1.3% a year since 2000.

Moreover, researchers at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO) assessed in 2013 that Russia lacks any policy whatsoever to address the issue of “intellectual migration,” concluding that the nation will be unable to fulfill any plans to economically modernize, so long as the number and qualifications of specialists exiting Russia vastly exceeds the number and qualifications of those entering. Earlier this year, Deputy Prime Minister Dmitriy Rogozin called Russia’s “brain drain” its greatest weakness. Ironically, he was unknowingly paraphrasing Atlantic Council director of research for Europe and Eurasia, Alina Polyakova, who in 2017 asserted that “this outward migration…is the number one threat to a Russian Federation that seeks to gain its foothold in the world again.”

Scholars at the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA) reported earlier this year that half of all Russian post-graduate students seek to gain employment abroad. Further, these would-be expats appear to fall into three groups: roughly a third have no intention of returning to Russia; roughly 15% keep tabs on the Russian labor market and would consider returning for the right prospect; around half do not rule out the possibility of returning to Russia—either permanently or temporarily—but their terms and timelines are yet unclear. In short, few of these advanced degree-holders appear to be firmly anchored to their homeland.

The U.S. would be imprudent to pass up such a strategic opportunity, and ought to promptly take efforts to seize it. Even more so since Russia’s own policy priorities, demographics, and culture essentially guarantee an increased rate of intellectual capital flight. Sergey Rogov, Director of the RAN Institute of U.S. and Canadian Studies, outlined in 2010 how a dismal record of funding and job prospects in science and research fields had left Russia with only 25,000 doctors of science—a quarter of whom were already past the age of 70. For comparison, in 2010 the U.S. alone was home to some 16,000 Soviet-era emigres of doctoral pedigree. In addition to this almost irreversible demographic trend, only 1% of Russians surveyed expressed respect for academic professions, compared with 56% of Americans.

These insights suggest that there remains a well of yet-untapped recruitment potential for the U.S. to pursue—in a way that would enhance its own long-term socio-economic development, while further hobbling Russia’s. Moreover, a “sanction” appealing to the aspirations of such a critical cross-section of Russian society would stand in stark contrast to economic sanctions that may only serve to galvanize public opinion against the U.S. and in favor of the Kremlin. Indeed, U.S. overtures of opportunity to an already-receptive Russian audience would be infinitely more difficult for Putin and his media minions to paint as an attack on the Russian populace than ruble-crashing sanctions have proven to be.

Further, a July 2016 study by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation suggests that such an approach would bolster already-successful U.S. efforts to attract highly-qualified talent into these fields. If the trends noted therein hold, by the year 2020, half of all STEM-focused PhD graduates will come from abroad—and half of those will intend to stay for future job opportunities. The National Foundation for American Policy in October 2017 similarly cited a host of evidence overwhelmingly illustrating how essential international students are “to preserving America’s role as a center of technological innovation.”

That preservation will only become more central to U.S. capacity to maintain its leading economic and security edge in the coming decades—a fact the Trump administration appears to acknowledge in the new U.S. National Security Strategy (NSS), unveiled last December. The document emphasizes “the importance of recruiting the most advanced technical workforce to the United States” and prioritizes creating jobs in STEM fields; attracting and retaining inventors and innovators; and understanding worldwide science and technology (S&T) trends.

Meanwhile, the Kremlin appears to appreciate, at least notionally, the geopolitical implications of the global competition for brainpower. For instance, last September Putin expounded on artificial intelligence to a group of students, claiming that “whoever leads in this sphere will rule the world.” This was not idle bluster – he was echoing what researchers at Harvard had concluded in July: that artificial intelligence has the potential to be as transformative to the world as the airplane, the computer, and the atomic bomb. If the U.S. and Russia are fated for strategic competition during such a transformative era—and if punitive measures against Russia are to be perpetually on order—now is the time for a strategic American investment in Russian brainpower.