Culture

Ethiopia Peace Corps Diary

Editor’s note: As the author adds more diary entries this post will be amended.

Part 1. Zewale Zegeye

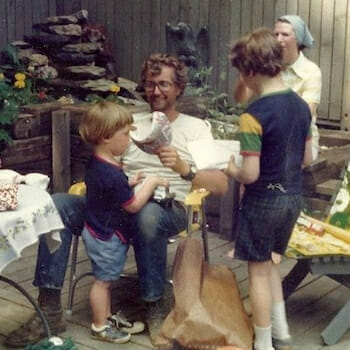

It was better than any college or high school reunion to see old friends and colleagues with whom 49 years ago I shared an adventure and life changing experience.

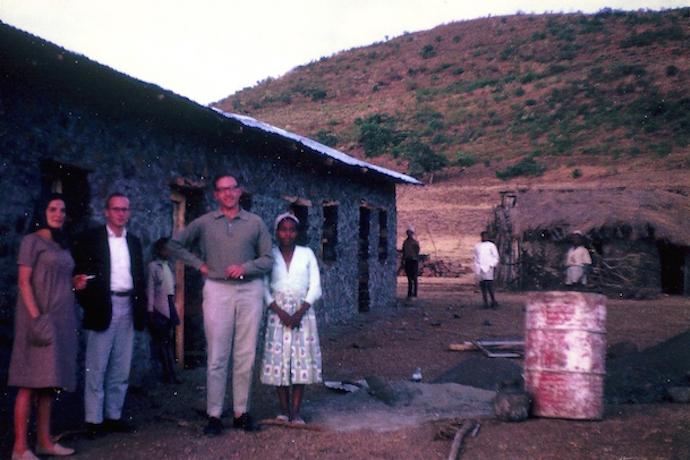

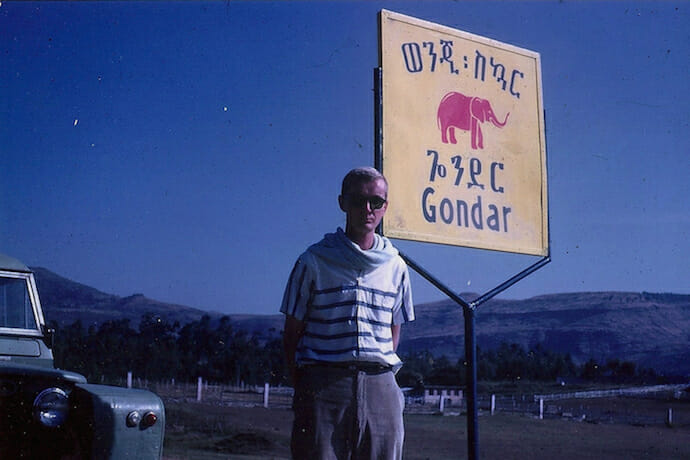

On September 13th, The Embassy of Ethiopia, in honor of the fiftieth year anniversary of the founding of the Peace Corps, hosted a reception and delicious Ethiopian buffet for Peace Corps volunteers who served in Ethiopia from 1962 through the start of the turmoil in the 70’s. It was my honor to be a member of “Ethiopia I,” among the first 280+ Peace Corps teachers invited to Ethiopia by Emperor Haile Selassie in 1962. At the time the secondary schools of Ethiopia were a bottleneck through which too few students were able to graduate and pass on for additional training and/or attendance in the University. Twelve of us were sent to Haile Selassie Secondary School in Gondar. It was the only secondary school in the large historic province of Begemeder in N W Ethiopia.

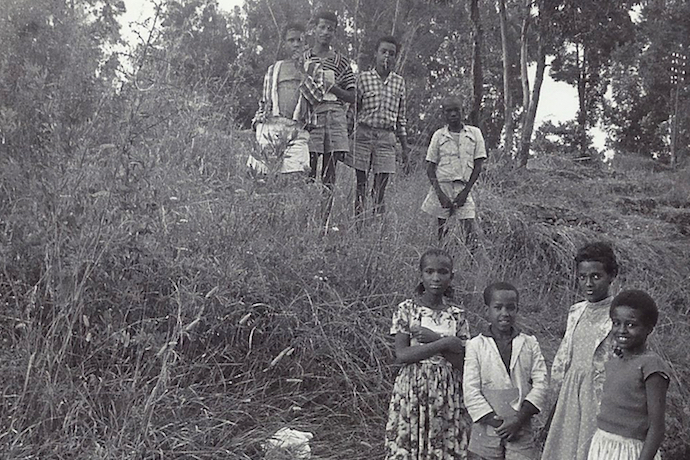

Students came from hundreds of miles from remote villages and farms to attend the school. If they had no family in Gondar they lived in improvised shelters and subsisted on an extremely modest government stipend. It was many a night that we would see students doing their homework while seated under the faint glow of the few streetlights in the town.

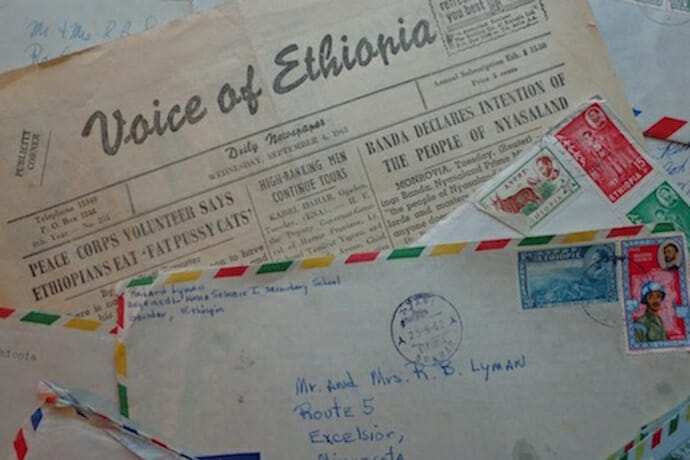

Five years ago my son, John, the editor of this Journal, persuaded me that it was time to revisit Ethiopia. At the time, John was studying in Paris so I “picked him up” and off we went to Ethiopia. In the back of my mind was a wish to reconnect with former students and to be able to write about their lives then and now and how they survived famine and the chaotic revolutionary decade of the 70’s. For the “then” part I have my detailed six volumes of diaries I kept while teaching. From my Mother I inherited a tendency to save everything so I even brought home a vast archive of student essays and papers.

Gondar is no longer a sleepy provincial capital. It now has a population of over 100,000 plus a university and even a modern beer plant. My expectation of reconnecting with former students was not met. John and I did, however, make wonderful new friends. My old school is still a big part of the community, however, now it is named Facilidas School after the ancient emperor whose palaces and public works abound in Gondar. The house where I lived surrounded by a five-acre field is now almost hidden by numerous houses. The house itself has been added onto and is now a school for over five hundred Montessori students. John and I had a tour of each of the thirteen classrooms where in each one the students performed a song or recitation in our honor.

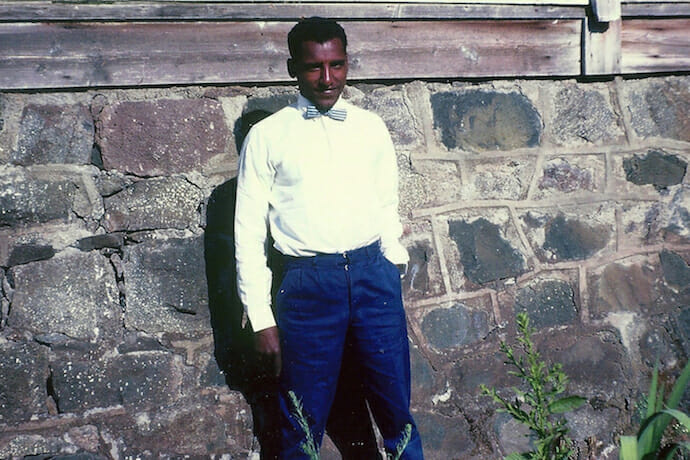

In one classroom we listened to an anti-corruption song. One of the many former students I hoped to see again was Zewale Zegeye with whom I had corresponded with into the 1970’s. At that time, I quit writing to him for his own safety as I thought with the revolutionary chaos the last thing he needed was to be accused of receiving letters from America. Zewale was a natural leader. He was the leader of the Scouting troop in Gondar started by Mr. Ward, the former British headmaster of our school, and was student body president in his senior year. Zewale loved to write plays, which we might view as being in a “Bollywood” genre. In my diary notation for May 18, 1963 I wrote of Zewale coming to my house late in the day because for the twelfth time he had to go to the local Ethiopian Government Ministry of Interior office where the officials had deleted lines from a play he wrote and planned to direct.

He was extremely upset and asked me “In America do you have to have your plays approved?” I replied “no” and then asked him a question whether in his lifetime he could remember when there could be no plays at all. He admitted that he could. We discussed the fact that small progress might give him hope for greater freedom in the future. I was reminded of my favorite Ethiopian proverb “Cus b cus inculal begaru ye hidal” (Little by little an egg gets legs and slowly walks away.” Zewale went on after high school to work in the office of the City Council in Addis.

This is an excerpt from the last letter I received from him in August 1970:

…Last year I ran for the parliamentary election to represent the town of Gondar, but I failed. The purpose of my competing was to awaken the people by telling them what I know and what should be done. I gave lectures for over ten times at the Haile Selassie 1st. Square in the Piazza of Gondar, under the big oak tree south of the Facilidas Castle on the way to the arada (market) if you remember it. I saw thousands of clapping hands during my lectures, but unfortunately those who were registered and who had most of the cards were those who know nothing about lecture and those who did not know what a parliament can do. Even most of the candidates were the same to them.

What I have seen is money electing people not people electing people. Anyway nothing can be finished unless it is started, so I will try again and again hoping to be a member one day, even though there are many obstacles which I should walk over.

I wish happiness, good health and good fortune to you and yours.

Sincerely your,

Zewale Zegeye

I learned while revisiting Gondar that sometime after that letter was written Zewale served as an administrator of a district north of Gondar near Dabat. While there he came to the attention of the military strongman in Gondar who assassinated Zewale by dragging him to his death behind a vehicle.

***

Part 2. Lalibela and a Mule Journey across Ethiopia

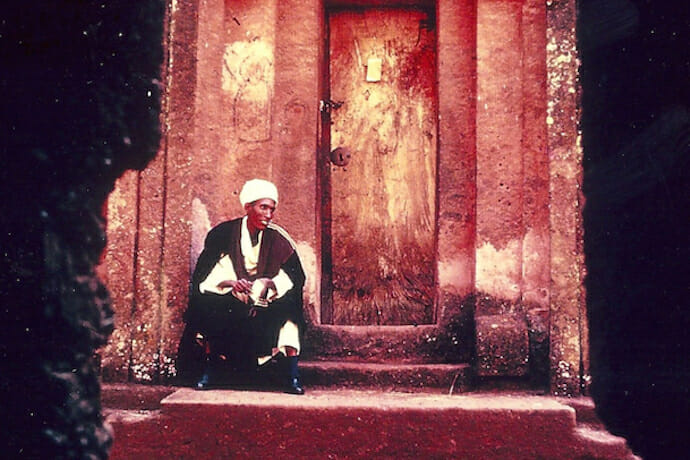

The Easter week break in our teaching schedule at Haile Selassie Secondary School in Gondar, Ethiopia afforded us time to pursue our fantasy of visiting the historic carved churches of Lalibela.

There were some complications, however, as there was no scheduled airline service nor roads leading to Lalibela. I urge you to Google “Lalibela” to see for yourself why UNESCO includes Lalibela on its list of World Heritage Sites. In the mountain village of Lalibela there are eleven large orthodox churches carved out of the volcanic rock. They are three stories high, carved on the inside as complete churches and are linked with passageways and tunnels carved from the rock. The origin of the churches is thought to be from the 14th. Century Reign of King Lalibela. Miss Marjorie Paul, a veteran USAID nurse/educator at the Gondar Public Health College used her connections to convince Ethiopian Airlines to fly us from Gondar to Lalibela. Miss Paul and three of us Peace Corps teachers who had saved enough money from our small monthly cost of living stipend from the Peace Corps to pay for only one way tickets.

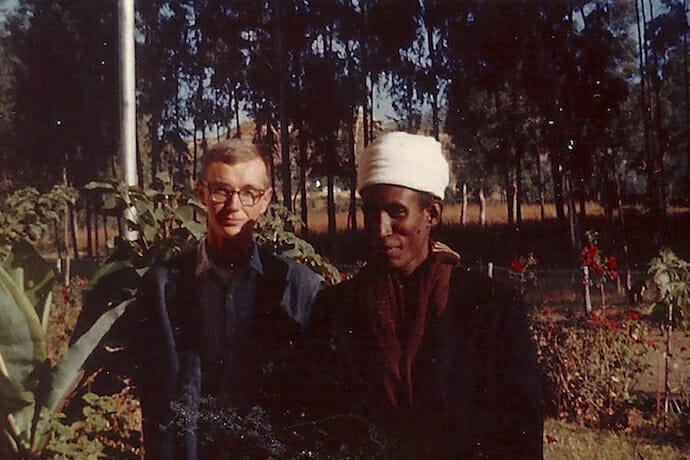

John Stockton, Jeff (Dallas) Smith and I shared the expense with Miss Paul. The airline agreed to let us bring along four additional passengers. We immediately asked Aba Gebre Meskel (the respected orthodox priest/morals teacher at our school) to join us. I intend in a future article to tell more about Aba Gebre Meskel. Three reliable students, Yimer Mekonnen, Kassahun Negussie and Ayalneh, rounded out our party of eight. The opportunity to see the churches of Lalibela was a lifetime thrill, but the journey to and from Lalibela was worthy of Canterbury Tales. I make no claim to being a Chaucer, however, what follows will be my diary account of our “Journey to Lalibela.”

On Saturday April 13, 1963 I wrote:

As we prepared to leave for the Gondar Airport, two priests who carried embroidered umbrellas and large silver crosses arrived at our house chanting and asking for money. After we complied they gave each of us a reed cross to be worn around our heads. The airport is about eight miles south of Gondar and four times a week a plane arrives there from either Addis or Asmara. The DC3 from Asmara landed on its way to Addis. The airline informed the through passengers and those waiting to board for the flight to Addis that they would have wait for a few hours in Gondar while we were flown to Lalibela. The land between Gondar and Lalibela to the east is crisscrossed by numerous river valleys. As we approached Lalibela which is situated on a high plateau, the pilot buzzed the village to let them know someone was coming. At some distance down the mountain was the landing field which had been plowed and harvested since the last flight the year before. Shepherd boys were herding cattle and sheep on the field. The pilot made several passes over the field in order to chase the cattle away. It was a safe although somewhat bumpy landing. We were met by about thirty people. Most of the men were dressed in skins. They brought mules for us to use to haul our 350 pounds of baggage (water jugs, sleeping bags, Miss Paul’s tent, clothes, food and primus stove). We haggled for half and hour before we hired enough men and mules to haul our gear to the top of the mountain. The trip up the mountain to Lalibela took us three hours. We found people washing their clothes in the streams which we forded in preparation for the Easter feast. Most of the people wore reeds on their heads. We could see Lalibela perched on a plateau in the distance, always several valleys further on.

We reached Lalibela just before the rains began. Ato Affework, Director of the Lalibela Health Clinic and Ato Berhanu let us camp in the storeroom of the clinic. The building was constructed of mud walls, a steel roof and a dirt floor.

After eating wat and ingera and drinking talla (beer) and teg (mead), Aba took us to the church called Lalibela. We crawled around in dark passage ways and sensed we were in the catacombs. After gaining permission to enter the church (it was given only because we happened to bring along a small green card we were given in Addis telling Ethiopians everywhere that we were to be “well treated” and signed and sealed by some important unknown official) we took off our shoes and entered Lalibela Church. The inside had a high vaulted ceiling with a series of carved pillars that gave the appearance of supporting the ceiling. In the first room women were seated on the floor in front of paintings of St. George with His Majesty Haile Selassie and another painting of Christ on the Cross. In one corner of the latter painting was a small image of the devil who was painted as a black man. All of the other images were painted with light skin. We then entered the second room where men were reading from holy books in Geez (the liturgical language) by light provided by burning twisted leather tapers. In the room was the grave of King Lalibela. The head priest seemed quite upset by our visit so we retreated to the Health Clinic to spend the night.

The sanitarian at the Health Clinic is responsible for collecting census data for the village of Lalibela which he shared with me. He tallied the Lalibela’s population as 1405 (900 female and 505 male). He further broke down the population by age groups, family size and occupation. I copied all the information into my diary. The most interesting set of data which I will repeat here relates to occupation.

Occupation:

Talla sellers: Females 298

Housewives: Females 205

Farmers: Males 115

Tailors: Males 23

Students: Males 63 Females 4

Priests: Males 44

Weavers: Males 14

Merchants: Males 44 Females 1

Monks: Males 4

Nuns: Females 50

Teachers: Males 2

Servants: Males 18 Females 49

Others: Males 189 Females 282

The one school in the village goes through the fourth grade. After that the students must go to a larger town in order to attend school.

Altogether, we visited nine of the stone churches. Two more are located some distance from Lalibela. Children followed us around all day. Every time we reached a wonza tree they would climb it to pick the yellow berries. The berries are extremely sticky when broken open. One form of celebration on Easter in addition to feasting is the hanging of rawhide swings from trees for the children to use.

The boys and girls had separate swings. The little boys brought us interesting crystals they found in the hills around Lalibela. On a hill above Emannuel church was a bell made from a large piece of basalt hanging from two wires. When struck with another stone it made a wonderful ringing sound. In most of the churches were electric wires with a few green light bulbs. I was told that Lalibela does not have electricity but when His Majesty visited several years ago a portable generator was brought in. In carved niches in passage walls were the bones of monks and priests. The bones were often exposed and at times were just lying around in dirty corners. From the ceiling of some of the churches wooden doves were hanging.

On Monday, April 15, 1963 I wrote:

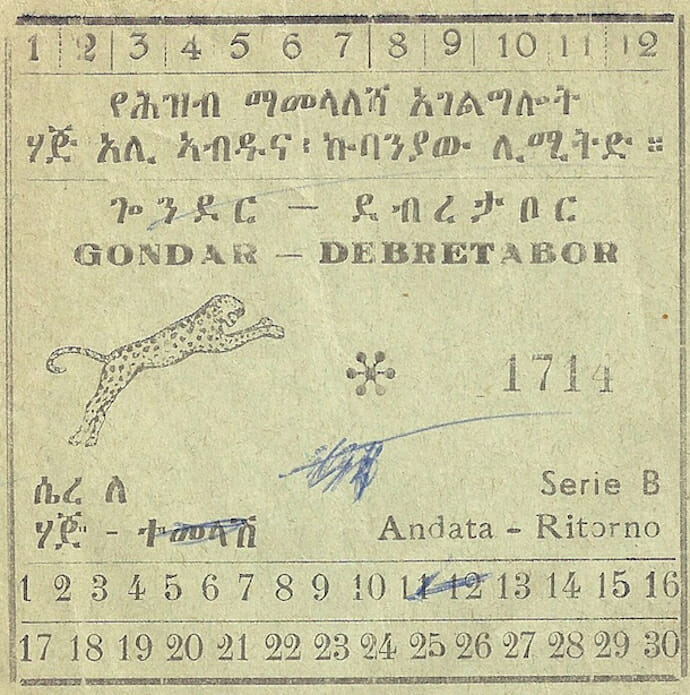

We got up at 5:00 to visit several churches while services were in progress . We chose to attend during the service so we could avoid the demands of the priests for money. After breakfast as we were waiting for our mules to arrive for our journey back to Gondar a number of priests came to the Health Clinic compound asking for money. Our mules were delayed because the Health Clinic sebana (guard) was trying to charge us $13 Eth/mule while the going price was only $10Eth/mule ($4US) for the trip to the next village of Gergera. Because we could not afford to have the DC3 return for us we planned to travel overland for five days in order to reach the city of Debre Tabor where we could take a bus the final 100+ miles back to Gondar. We had no map and there was no road so we had to rely on the mule men to guide us from village to village.

As we waited for the mules to be assembled we watched several men slaughter a calf at the edge of the market. By 12:15 we had two pack mules and three riding mules and we set off for Gergera. With us were three mule drivers. We retraced our route to the landing site before heading to the Tekeze River. Because it was the end of the dry season all the rivers we encountered were easily forded. Most of the way we journeyed down to a lower elevation. Around the Tekeze and the Abebe Rivers there was no human activity. About 4:00 we began to look for a village in which to spend the night. We journeyed on until 8:30 (two hours after dark) and finally told our mule men to unload the packs and we camped for the night in a plowed field.

On Tuesday, April 16, 1963 I wrote:

We arose at 5:30 and were ready to leave by 7:30. For breakfast we ate oatmeal/teff porridge and tea. In the distance we could see Gergera perched atop a plateau. We crossed quite a wide plain cut by several streams from which we quenched our thirst.

Overhead we could see the Ethiopian Airlines jets on their way to Addis from Europe. Although we didn’t see any, we noted evidence of hyenas from their white stools. Two of the river valleys we had to cross were the Deremo and the Twota Bahir. After crossing the Twota Bahir River we began to climb upward to the Gergera plateau. On the way we rested outside the Degas Mariam Church. Walking with us were several Ethiopian wood carriers on their way to Gergera. Wood carriers are often extremely poor older women who are bent over from bearing large bundles of wood on their backs. Once we climbed onto the plateau we discovered that there was still another one we had to climb in order to reach Gergera. Our mules couldn’t negotiate the final climb so we all had to dismount and lead them up the mountain.

In addition to the usual volcanic rocks there appeared to be a chalky sandstone material. All of the villages are concentrated in the highland regions because of the fear of malaria. On the way up the cliff we passed 100’s of monkeys which live undisturbed on the slopes. When we reached the top we rested outside of St. George Church. All the mule men devoutly went to the wall and kissed it. Gergera itself is run by a priest while the neighboring village of Feleka has a sub-district governor.

The whole plateau was green as the rains had already come. After stopping for Teg and Talla in Gergera we carried our belongings to Feleka where we met the sub-district governor. We were assisted by a young Air Force officer who was returning to Feleka for a 21 day visit with his family. The sub-district governor whose name and title is Fitarare Tefere Yimer invited us in for teg, talla, araque (distilled spirits – strong!!) and wat and ingera. Because it was dusk he prepared a camping place for us on the edge of his compound by spreading rugs and putting up a canvas awning. Ato Negussie, the director of the school, invited us to inspect the school and have dinner at his house. The school goes through the fifth grade, after which the students go to Dessie to school. As we prepared for sleep Fitarare Tefere checked to see that we were comfortable. He left six guards to look after us all night. Ato Zewdu Tekle, the secretary to the governor, brought out a five gallon earthen jug of Talla for us to consume during the night.

On Wednesday, April 17, 1963 I wrote:

By 8:00 we were ready to leave, that was until the governor invited us in for tea, araqua and alecha and lamb wat. The governor had three young boys as servants. The governor’s wife sat in one corner on a straw mat while he sat on sort of a low couch.

As is the custom Aba delivered a prayer at the conclusion of the meal. The region is quite cold so there are small fireplaces in most homes. We followed the governor’s example and threw our bones on the floor. We finally left at 9:30 after taking the governor’s picture. He conferred the title of fitarare upon us. Fitarare is a noble honorific title reserved for those who are “up in the front” or we might say generals in the army. The four mules we rented included one of the governor’s which was so spirited that Dallas fell off of it by 10:30. Dallas became ill in Lalibela so he rode most of the way to Debra Tabor. Miss Paul also was a frequent mule rider. The rest of us found the mule saddles so uncomfortable that we walked the distance.

Although it was Wednesday we were served meat. After the Easter fast there is an equal period of no fasting – not even on Friday or Wednesday. As we crossed the Debre Zebit plain we could see Mount Guna in the distance. Often when men riding mules would pass us they would get down from their mules to greet us. As is the custom, several mule riders offered those of us who were walking the use of their mules. That was even the case if it meant that they would have to journey with us back to where they came from. We politely thanked them and declined their offers.

On the plain which is poorly drained and not cultivated were hundreds of head of grazing cattle. Most cattle herds were small consisting of eight to twelve head. Each small herd was watched by boys who were wearing skins if they had on any clothes at all. They may have never seen foreigners because they ran away when we approached them. After ten miles we reached the end of the plain and descended onto the remains of an old Italian road. The road wound around the mountains and is little used except by mules and people on foot. The road was constructed of large stones placed closely together. Near the end of the trail as we approached the village of Nafas Moche we saw many acacia trees. At one point we rested near some brushy trees and Kassahun broke a branch off the shinshina tree and presented me with a piece to use as a tooth brush. Nefas Moche is atop another plateau and we were told the name relates to its windy nature. We slept on the concrete floor of the school house. Aba and John walked into the town and ate at an Ethiopian hotel. In the hotel people were gambling with dice which greatly interested Aba.

On Thursday, April 18. 1963 I wrote:

We arose at 6:00 for our usual breakfast of oatmeal/teff/raisin porridge and tea. Our water cans were filled from the river and treated with iodine tablets at the rate of 1/pint. At 8:00 the secretary to the governor invited us to his house for alecha wat, talla, teg, beef steaks and quantro (strips of dried beef which are fried). The trail out of Nefas Moche was very poor, badly eroded and full of boulders. About an hour out of Nefas Moche we came to a wooded waterfall with monkeys all around. The trail doesn’t follow the old Italian road instead it follows a telephone line which we assume is the most direct route. Along the way many people passed us en-route to Nefas Mocha for a feast given by the governor.

Several times we were overtaken by government couriers. They were dashing young men dressed in white riding the finest mules. They rode straight in the saddle with the help of their big toes through the stirrups. They would dash off over the next hill in a cloud of dust with red tassels flapping from the raw hide harnesses across the back of the mule. At one point the expected happened and our pack mule threw off its load thus tearing Dallas’ sleeping bag. John, Aba and I walked on while the two mule men fixed the pack. We were joined by two lean, weathered country men who were walking from Dessie to Gondar. They each carried a long wooden staff upon which at one end they had secured their goods and food for the journey. When country men walk with such a staff they frequently place it across their shoulders behind the head.

Then they walk along with their wrists draped over the staff on each side of their head. The two men stopped and shared with us a taste of their lunch of dabbo kola, little balls of dough cooked with roasted grains inside.

The dabbo kola was somewhat spicy because berberi had been added to the dough prior to its being formed around the grain. We were walking on the south rim of a large valley when we saw several miles away on the north side of the valley a large encampment of mules and merchant traders. For safety reasons we decided it best to avoid them and not make them aware that we were traveling without an armed escort. Hours later we could see a small settlement off to our north. Yemir told us it was his village. We asked if he wished to stop to see his family since he had not been home for years. He declined saying “The visit would be too short that it was better to not stop at all.” Late in the day we came to the village of Kemer Dingay (pile of rocks) where we spent the night. We were joined by a thirty year old judge from Nefas Moche who was traveling with his wife and young son to Debre Tabor for a feast at his brother-in-law’s. We arranged to sleep in the house of the local chief. The house had a radius of about ten feet and in the center next to the main pole was a fire pit.

Although the outside walls weren’t plastered the inside walls were plastered in mud. The door was a mat of woven split bamboo. The local governor brought us eggs, chickens and talla. The judge’s wife prepared the food. She cleaned the chickens in a very unusual fashion. After they were killed and picked she removed the legs and the wings. Then she made a slit in the back and broke the chicken in half thus removing the insides. Our old mule drive came into the house looking for food and drink. Aba and Ato Mulugeta (the judge) sent him away by insisting he check on the mules. The old man was from the Feleka governor’s court. We discovered that he was something of a court jester with plenty of songs and jokes. We sat around on the dirt floor to eat our meal. Prior to being served a servant surprised us by bringing a basin and pitcher of warm water with which to wash our feet, a truly Biblical experience. A man from the village approached Ato Mulugeta about a parcel of land in another province that had been taken away from him.

He had spent a year in Addis trying to get it back from the government. The government had finally given him a gasha of land in the Southwest that was taken from the Gallas. Land reform in Ethiopia thus far seems to mean taking land from the Gallas and giving it to Amaharas. The man estimated that he can earn $1,000 Eth. /year ($400 US) from the gasha (100 acres). During the night we heard a religious fanatic yelling around the village.

On Friday, April 19, 1963 I wrote:

We got up at 6:00 with the rest of the village. The chickens were the alarm clock. We slept quite comfortably on the floor of the house in our sleeping bags. Once or twice during the night a small rat came out of the wall to visit us but never stayed long. We did, however, find the chicken bones on the floor somewhat bothersome. During the meal the bones had been cracked open by our student travelers to extract all the marrow. The rather wild mule got away from the old mule man so we got a late start. It didn’t matter as it was only five hours to Debre Tabor over relatively gentle land.

We sojourned on led by the wife of Judge Mulugeta who rode first carrying the child who held the most beautiful red flower I had ever seen. With her was one gun bearer. The judge followed on another mule followed by a second gun bearer. Judge Mulugeta’s father is a district governor.

The Judge related to us that he had gone to Addis to find his beautiful wife at the Ghion Hotel. We entered the town of Debre Tabor which is surrounded by huge eucalyptus trees. We stopped at the Seventh Day Adventist Mission and were warmly received by the Andersens from Denmark. He is the director of the school which runs through the eighth grade. After that the students go on to our school in Gondar. The mission was started in 1932 and operated during the Italian occupation. There is also an affiliated hospital run by Dr. Hoganva from Norway. He has designed and is supervising the building of a lovely new clinic. We were met at the mission by some of our students who took us into the center of the town. Prior to the Italian build-up of Gondar, Debre Tabor was the principle city of the province. In one of the tea houses we drank sweet tea and were amazed to be served Parker House rolls. We learned that the tea house is owned by the father of one of our students and that he learned to make the rolls while living in Addis.

The Andersens eat no meat so they have huge gardens containing tomatoes, ground cherries, passion fruit and all kinds of greens and flowers. They served us a superb meal with many kinds of cheeses and pastries. During the day we learned that a dead man had been brought to the hospital by an excited crowd of people who claimed that the man had caught a hyena in a trap and that as he killed the animal it breathed into his face thus causing his death. As we were finishing our meal the bell rang for the Friday night religious service which we attended. The auditorium was quite large with rows of backless benches. It had all been freshly scrubbed in the afternoon by the students. All the boys sat on the right side with the girls filling the middle and the left side. The hymnals were in Amharic and English but most of the songs were belted out in Amharic. We slept the night on the floor of Dr. Hoganva’s house.

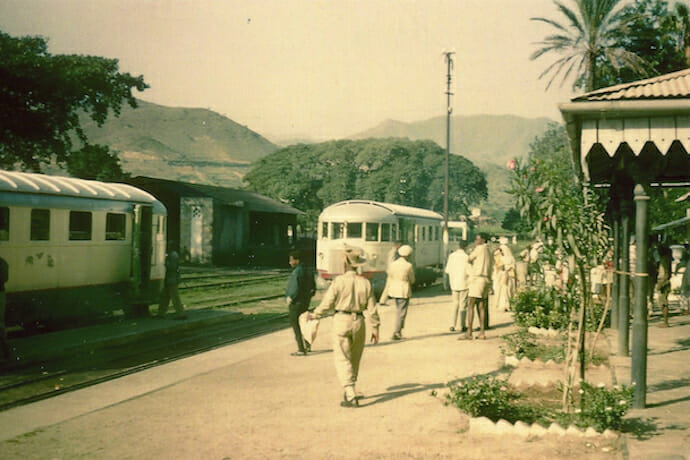

On Saturday, April 20, 1963 I wrote:

We were ready to leave at 6:00 when the bus to Gondar arrived on the mission compound. We had made arrangements the day before but never dreamed that it would be on time. The 100+ mile trip to Gondar usually takes seven to eight hours. The bus was mounted on the back of a Fiat truck. When it was fully loaded it contained about 40 people. Between Debre Tabor and Adi Zemen we had to ford twelve streams because the bridge timbers had been removed from the old Italian bridges. The road itself is seldom repaired and is barely passible in the dry season.

The trip to Adi Zemen took five hours. All along the way we stopped to pick up passengers including two of our students who were patiently waiting beside the road to catch the bus to return to school in Gondar. On one mountain stretch we came upon a Mercedes truck loaded with kerosene drums headed in our direction. We parked on one side of the narrow road and the truck passed us on the other with one to two inches to spare between the vehicles. The five most interesting people on the bus were seated in the front seat facing backwards. On the left was a two star army officer who was so heavy he couldn’t get his jacket buttoned. He wore an open yellow shirt covered with a green sweater. Around his neck was the familiar red string showing he was a Christian. Next to him was a student with a shirt from England which proclaimed in splashy letters “Elizabeth,” “Africa,” “Ghana.”

He carried a liter bottle of araque but it soon was broken by the rough ride. The liquid flowed under all the seats and was so strong that some passengers threw their shamas over their faces. Next to the student was a farmer with the fiercest eyes and expression which mellowed when he got sick and dove for a window. He wore a peppermint stripped string around his neck. In addition he wore a khaki jacket and shorts with a shama and finally an ordinary bath size towel. The last two people were a ras (local village leader) and his young wife who was sick most of the trip. The ras wore the usual khaki slacks and jacket, a British army wool overcoat and then a shama. We were warm in just our tee shirts and shorts. We were very touched by the concern he showed for his wife. At Adi Zemen we met the bus going to Addis. Our intended one hour rest stop stretched into two hours when our driver was hauled before a local judge. He was accused by someone of carrying chickens on the bus on a prior trip. There are rules against hauling livestock and passengers together (thank God). Also there is another rule that berberi cannot be transported on a bus.

From Adi Zemen the American built road to Bahir Dar is almost completed and while only gravel it is like a freeway. On the final leg of our journey from Adi Zemen to Gondar a wizard boarded the bus and promptly became bus sick. He had mud caked hair, rings on every fingers and strings and strings of charms around his neck. Late, late in the day we arrived home in Gondar and fortunately because our house was directly on the north/south highway we were dropped off exhausted and dirty at our front door.

Special note: Lalibela is a magical place so please Google it.

***

Part 3. Meeting Emperor Haile Selassie

As with my two previous posts I am drawing stories from the diary I kept while a Peace Corps Volunteer teaching in Gondar, Ethiopia.

In Amharic the word “tarik” has the meaning of both “story” and “history” so this is my “tarik.” I’ve told my son, John Lyman, that I will try each month to provide a new “tarik” until I exhaust the material. There will be no chronology to the stories. My daily diary entries are essentially a verbal record. There were no newspapers and radio was limited to the BBC, VOA and a few eastern block stations. News in the government newspapers printed in Addis usually revolved around which factory HIM (His Imperial Majesty) visited.

My information was gleaned from conversations with students, colleagues, the citizens of Gondar, other foreigners working in Gondar and occasional visitors to Gondar who would bring news and rumors of happenings in the capital. My spelling of names and places is based on what I heard and is not taken from any official documents or memos.

Amharic has its own alphabet so when I transposed Ethiopian names into English there was a great deal of spelling flexibility. I landed in Ethiopia on September 6, 1962 and stayed in Addis for two weeks until September 21, 1962 at which time eleven of us were flown to our new home in Gondar. The purpose of the two weeks stay was officially called an “orientation” period. However, we suspected it was to give the Peace Corps time to sort out where we were assigned and to make final housing arrangements for us. During the two weeks in Addis we were treated to several wonderful events.

On September 8, 1962 I wrote:

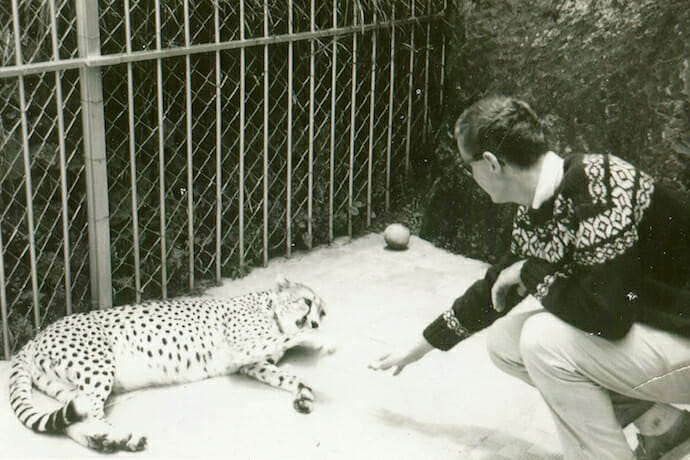

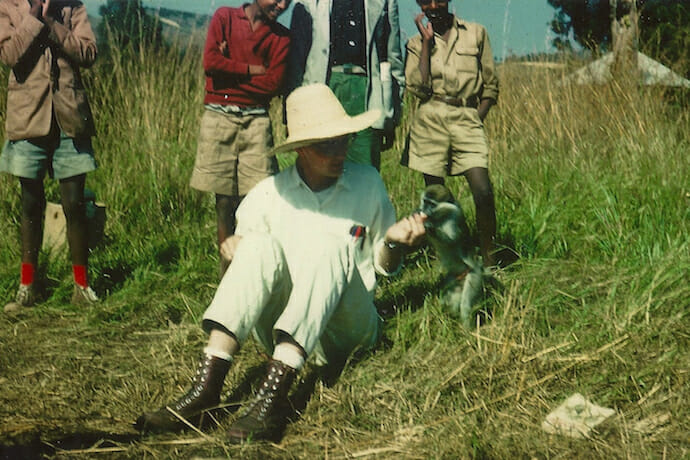

It was Saint Johannes day so we were transported in Italian buses to St. Johannes church over narrow roads clogged with pilgrims. The buses nearly hit several cars, horse drawn wagons, beggars and pilgrims. We were next taken to Africa Hall which was built by Haile Selassie at a cost of $6 million(Eth.) to house the Organization of African Unity. The front of the building contains a striking stained glass image several stories high. Africa Hall is across from HIM’s Jubilee Palace which was built in 1955. Haile Selassie has many titles. Among them: Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, Haile Selassie 1, Elect of God, Emperor of Ethiopia and Keeper of the Seven Umbrellas. Someone obtained permission for us to visit HIM’s private zoo and formal Japanese garden on the grounds behind the palace. We were told His Majesty’s cheetahs were tame so I entered the cage to pet one. Everything went very well until some fellow standing outside the cage dropped his umbrella and startled the animal. There was a brief period of uncertainty as I hastily exited the cage. I did, however, have a friend on the outside who captured for posterity the event on film. We emerged from the back of the palace in time to witness HIM leaving the grounds in his maroon Rolls-Royce surrounded by his machine gun armed body guard. (On a rare visit to Addis the next year I was driving a Jeep when HIM approached from the opposite direction. As everyone else does, either through custom or law, I got out of the Jeep and bowed as he passed. The act of bowing did not offend my democratic sensibilities as I had great respect for what HIM was attempting to acomplish in Ethiopia).

On September 11, 1962 I wrote:

Today is New Years Day in the Ethiopian calendar. The Ethiopian calendar consists of twelve months of 30 days and a thirteenth month (Pagume) consisting of the remaining five or six days, depending on whether it is leap year. To celebrate New Years day we were honored to be invited to the homes of hundreds of Ethiopian officials. George Parish, John Stockton and I went by VW to the home of Ato Mulugeta Gebrewold who is with the Development Bank of Ethiopia. He is unmarried and lives with his two sisters and aunt in her home which sits right on the street a short distance down the hill from the Piazza. His mother lives in the provinces and we were told that his older brother and father had been killed. The celebration began with glasses of home brewed talla beer (growing up on a farm it reminded me of burned barley). Then followed glasses of teg (mead/fermented honey). The meal was served on a two and a half foot tall elaborate woven basket table. Layers of ingera were spread on the top of the basket. (Ingera is a flat bread made from teff flour. Teff is a fine seed grown in Ethiopia which, unlike our wheat, contains no gluten. Thus, when teff flour is mixed with water and allowed to stand carbon dioxide bubbles off instead of the dough rising. The flat ingera has the appearance of tripe and has a wonderful slightly sour taste).

On top of the ingera were about ten different wats (spicy sauces). We were shown how to break off pieces of ingera with our right hand and dip it into the sauce of our choice. We made note of the location of the raw ground beef wat and did our best to avoid it. Ato Mulgeta’s Aunt was a most gracious hostess and she introduced us to the custom of “gosha.” (My sons tell me that Ethiopian food and “gosha” have now entered our popular culture because the “Simpsons” have recently been shown enjoying it while eating in an Ethiopian restaurant). I was seated next to our hostess so she repeatedly reached into the common table and gathered up large handfuls of wat and ingera which she plunged into my mouth.

In the spirit of the day and being a good guest I ate and ate. Only when she gathered a large handful of raw beef and fed it to me did I make a decorous retreat to the WC. In addition to the many wats. at the end of the meal we ate dabbo (a type of bread soaked in something so it was like cheese cake). After the meal we were served demitasses of coffee with a spoonfull of sugar in each and tea made with cloves. We then talked and played cards (a form of rummy called conquer). While we were drinking more teg, a dozen neighbor children came by singing songs celebrating the end of the rainy season. After Ato Mulugeta gave them several dollars they sang a final song of thanks in which they wished that the host’s house would have one more child when they came next year.

On September 20, 1962 I wrote:

At 4:00 HIM invited all of us to return to the Jubilee Palace for a reception. We entered through the front doors which were guarded by His Majesty’s two cheetahs. I greeted the one as an old friend. The reception room contained three huge chandeliers. We were served champagne from his finest crystal goblets. In my TWA bag I smuggled in my small Philips tape recorder so I was able to record a “bootleg tape” of Harris Wofford’s introductory remarks and HIM’s welcoming speech. (Harris Wofford was living in Addis and serving as Peace Corps African Director. It was a pleasure to work with Harris.)

When HIM is driven through the streets his two small papillon dogs accompany him. During the reception they were very active at his feet. (A “tarik” we heard later while teaching in Gondar was that Ethiopian government ministers when received by HIM were sniffed by the dogs. If the dogs registered disapproval of the minister, that person might find his standing with HIM impacted.) My tape captured several moments when the two dogs barked as HIM was speaking and he responded by verbally reprimanding them. Following the remarks of HIM we were each invited to step forward and shake his Majesty’s hand and then back away from the throne.

A few years ago when Dallas Smith was at my home for dinner he and I entertained family and friends with our stories of life in Ethiopia in the 60’s. Dallas felt duty bound to add a footnote to our story of meeting HIM at the palace by revealing to everyone that when I stepped back after shaking HIM’s hand I stepped on one of the royal dogs. I had neglected to mention the incident in my diary.

***

Part 4. 300 Gondar School Gardens

The “Gondar 12,” Madelyn Engvall, Jack Prebis, Charlie Callahan, Frank Mason, Andrea Wright, Patricia Martin-Jenkins, Peggy and John Davis, Martin Benjamin, John Stockton, Dallas Smith and I, arrived on the flight from Addis.

Gondar is in the historic, traditional and remote Begemedir Province which stretches from north of the Siemien Mountains to the south of Lake Tana (the source of the Blue Nile). We were assigned to the only secondary school, Haile Selassie I Secondary School (HS1SS), in the vast province.

On September 21, 1962 I wrote:

The ‘Gondar 12,’ Madelyn Engvall, Jack Prebis, Charlie Callahan, Frank Mason, Andrea Wright, Patricia Martin-Jenkins, Peggy and John Davis, Martin Benjamin, John Stockton, Dallas Smith and I, arrived on the flight from Addis. Gondar is in the historic, traditional and remote Begemedir Province which stretches from north of the Siemien Mountains to the south of Lake Tana (the source of the Blue Nile). We were assigned to the only secondary school, Haile Selassie I Secondary School (HS1SS), in the vast province. Gondar was established as the center of the Empire by Emperor Fasilides in 1635. He and subsequent kings built fine castles and churches there for the next two hundred years. Emperor Tewodros moved the capital to Magdala in the mid 19th Century.

We knew Gondar was remote from the fact that HIM (Haile Selassie), when he had a problem with a student leader at University College in Addis, would send the student off into exile as a teacher at our school in Gondar. One such story I recorded in my diary:

Ato Gebeyehu came over to our house for lunch. He is really a bright fellow having been educated for a year in Oslo and traveled widely in Europe. He claims to have a PPE scholarship to Oxford but the Ethiopian government won’t let him leave the country again. For the first two terms of this school year he was exiled to Debre Berhan near Addis but this term he has been sent to Gondar as it is further away. His problem with the government stems from the fact that he is so articulate and was president of the University College student body last year. When the students protested the refusal of the government to reopen the closed dormitories, he was forced to leave University College. The students threatened further strikes unless he could return so he is supposed to be re-admitted for his senior year next fall. The dormitories were closed because they were becoming a center for student exchange of ideas and thus the government is now trying to disperse the university students throughout Addis.

My best estimate for the number of students at HS1SS was under 1,000. I base this on my experience helping the Gondar Health College vaccinate the students for smallpox. That day I sat at the table and checked off 900+ names as the students bravely approached. The health workers would then swab their arm with alcohol, apply a few drops of vaccine and then punch it in through the skin using large dull needles. I would then collect the needles in a small tin and as needed pour in alcohol and light it to sterilize them.

In the Empire national examinations were given to students completing the eighth and twelfth grades. Only three of the previous year’s twenty-four seniors passed the exam. To go on for further education students needed to pass those tests. That first year the twelve of us from the Peace Corps had very little contact with the twenty seniors and small number of eleventh grade students. That was because there were five contract teachers from India who had seniority and only taught one subject,either English, Mathematics or History. We thus were assigned what was left over.

Other staff were: Ato Kettema Kifle, the director, Mr. Ooman, his very capable assistant from India, a British couple under contract, Larry and Pamela (Hebe) Marston, a school secretary Ato Shiffera (the son of the District Governor of Chilga), Aba Gebre Meskel, the school priest and morals teacher, and about a dozen Ethiopian teachers.

The first Ethiopian teacher I got to know was Ato Demussie. He expressed his frustration with the passivity of some of the students by saying “They want us to take knowledge and hang it around their ears like bells.”

Classes began on October 1 after all the assignments were worked out and the students registered. All instruction was in English. This was the first exposure to the English language for the seventh graders. The school day began at 8:20 with the ringing of a bell made from an empty WWII shell and ended at 4:45. There was, however, a two hour break for lunch.

Over the two years I taught 10th grade math to night school students (policemen and students at the Health College), 7th grade science, 8th grade math, 9th grade geography, 10th grade Math, 9th and 10th grade agriculture and 200+ 7th grade students gardening.

As it does today, the school (bearing the new name of Fasilides School) sprawled for about 1/3rd of a mile along the road from the Bath of Fasilides (a unique 17th century castle standing on pillars in a pool) towards the center of town. I was asked to be the garden master over a fertile area just opposite the Bath. On the site was this mysterious small round stone structure which was locked-up and for which no one seemed to have a key. It had a small high window through which I boosted one of the small seventh graders and he opened the door from the inside. It turned out to be an abandoned well house built during the Italian occupation. I replaced the lock with one of my own and used the building as storage for all the tools (sickles, pick-axes, shovels, watering cans and hoes) which the children would need.

Each school in the Empire had a storekeeper who was personally responsible for all books, tools, and materials. Our storekeeper tried his best to be helpful. He, however, was personally financially liable for all materials.

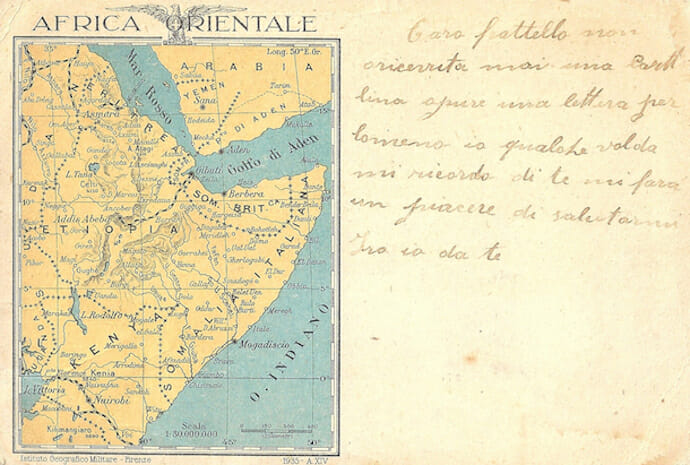

Therefore, we had to sign for everything we checked out of his storeroom with the knowledge that in order to leave the Empire in two years we would have to have a signed paper from him stating that everything was returned. I had been warned that a previous garden master had had 11 sickles and 14 pick-axes walk off the school ground. Elsewhere in the Empire some other Peace Corps teachers reported that their storekeepers protected themselves by simply not allowing books and materials to leave the storeroom. On the back wall of the storeroom I discovered a map from the ‘30’s showing Ethiopia as a part of Italian East Africa.

There were very few textbooks and those we had were often of limited help. I recall that the seventh grade science books had chapters titled: “Birds of the Moorlands” and “Twigs in Winter.” We had to create our own books by standing at the blackboard and writing and writing and the students would copy and copy it all into their copy books.

At Carleton College we were required to wear coats and ties to dinner so, somewhat out of defiance, I purchased a denim blazer on which I sewed the college badge. That was my standard uniform in Gondar. The two large pockets were always filled with many pieces of chalk. Only after several weeks of teaching did it dawn on us that we were talking too fast and the students were having trouble understanding our American English. In five of the schools in the Empire, the Ministry of Education was experimenting with the teaching of agriculture. Ours was one of those and I, along with John Davis, team taught agriculture. There was no curriculum, no funding and no materials.

USAID shipped two dozen new typewriters to our school but they could not find a dozen leghorn chickens in the Empire to send me. I decided that my 50 eager students were unlikely to return to the farms of their fathers. However, because they might become teachers or possibly work with farmers, I believed that they should thoroughly understand the science of growing things. Thus, I spent a great deal of time teaching them how plants and animals, including humans, utilize nutrition, minerals etc. The students often shared their common folklore with me about such things. All the salt in the province was excavated in the Danikal depression and was sold as blocks or in bulk in the Saturday market. It was not iodized and because of the leached out soils in the area, goiters were a big problem.

After a lesson teaching about the body’s need for iodine, a student, Abderman, came up to me after class and gestured with his hand around his neck to indicate where a goiter could develop and then asked, ”Sir, you mean if I sleep with a woman with this I will not get it?”

When the new USAID typewriters arrived at the school all the students wanted to learn to type. Having the typing skill was viewed as a pathway to a comfortable government job in Addis. Dallas Smith was asked to teach typing. He wrote a list of “rules” for taking typing in order to maintain decorum and the equipment. Some of the rules related to having clean hands and trimmed fingernails. The latter requirement posed a cultural conflict because Begemedir was the heartland of Amhara tradition and one of the local traditions observed by many was to grow a long nail on the little finger of one hand thus showing that one did no manual work. The desire to learn typing trumped tradition for almost everyone. On the first day of typing class Dallas stood in the doorway with nail clippers at the ready.

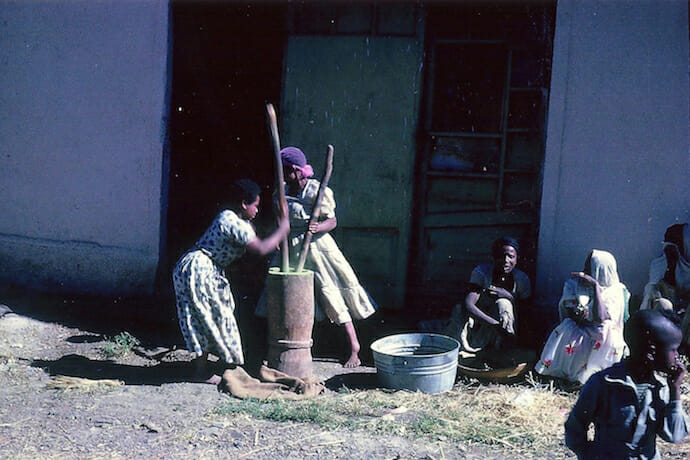

I spent time with the students in the gardens after school and on Saturday mornings. They took great pride in their small plots. On December 11th I observed some of the 7th graders proudly marching around the school compound showing off the radishes they had grown. There were many instances when students invited me to their houses and proudly showed off the gardens they had planted for their families. All but one student, the son of a minor local nobleman who regularly sent his servant to weed his garden, received a very high grade in the class.

Each of the 200+ students tore a page from his/her copy book and wrote an essay about his/her garden. I brought all the essays home and in reading them for this article I noted that many of the students, in addition to furnishing their homes with vegetables, sold several dollars worth of produce in order to buy pens and copy books. They wrote very eloquently in spite of their limited exposure to English.

Genet, a seventh grade girl had this to say (I made a few edits):

Our school garden is very powerful because it has many uses. Some uses are as follows. It gives energy or force. It protects from some diseases. I have very good plant in our school. I liked Cabbage, Salade, Costa, Tomato, Carrot, Beet Root and so on I planted in the school some seed and it will became big I take from our garden place to my house and give for my mother. At that time my mother happy by some plant because she know the uses of plant and she thank a lot me.

Considering the turmoil that Ethiopia has experienced over the past fifty years, I believe that the simple skills I taught about growing one’s own food may have been the most useful survival skill I offered my students from whom I learned so much.

***

Part 5. Passover with the Falasha Jews of Ethiopia

In the early 1960’s from north of Gondar in the Simien Mountains to south of Gondar in Ambover there lived thousands of Falasha Jewish Ethiopians. The name “Falasha” is not politically correct today, however, it was the only name we ever heard used. Since the 1980’s over 80,000 Ethiopian Jews have been permitted to “return” to Israel. Within our school in Gondar we were told that there were three Falasha students, however, no one was ever identified. Once in my classroom I broke up a severe teasing episode where one of my students was being accused of being a Falasha.

A number of times I visited the tiny Falasha village located only a couple of kilometers north of Gondar on the Asmara road. It was close enough to Gondar to be a pleasant walk. I never heard a name for the place. It was situated on a knoll around which the road swung. There were just a few round, wood post houses, plastered with mud with straw roofs.

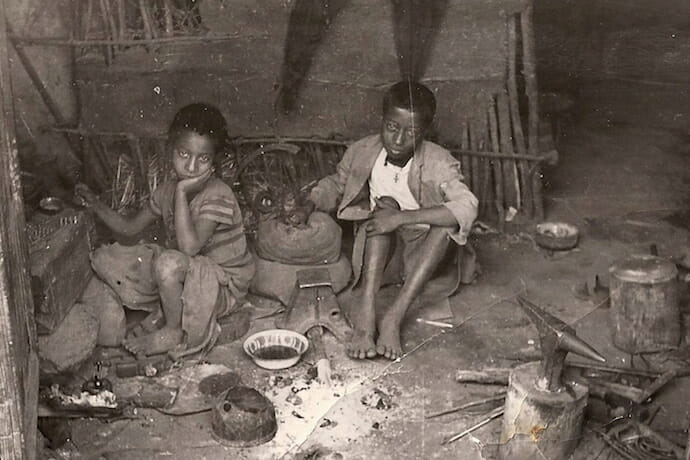

The men were primarily employed making steel farm implements while the women were potters. The Falasha of Ethiopia were not allowed to own land so this particular village did not appear to be heavily involved in agriculture, although there were chickens, sheep and cattle wandering around, occasionally into the houses. In a future article I intend to describe the difficult land ownership situation in Northwest Ethiopia at the time I lived there.

Miss Marjorie Paul, one of the USAID nurse/instructors at the Gondar Health College took an active interest in the Falasha. She confided to me that shortly before we, the Peace Corps, came to Gondar she had encouraged and shown the Falasha women potters how to make small animal sculptures to sell to tourists who regularly visited Gondar.

Following my last visit to the village on April 19, 1964, I made this entry in my diary:

I walked out to the Falasha village to buy some pottery to take home in July. On the way I joined two men who were carrying a large steel beam that they were planning to use to make plow points. The steel beam was left from WWII so they were truly going to “pound swords into plow shears.” Once in the village the men assembled under a tree where they had a charcoal fire burning which they enhanced by working two sheep bladder bellows by hand. Once the fire was hot enough they pounded the red hot portion of the beam in order to work it into plow points. Seated near by on a little camp stool was a large Israeli artist who was sloshing oil paint onto a canvas, seeking to capture the essence of the Falasha men working. Like myself, the ironworkers appeared to be very amused by his creation.

I purchased pottery from Ester Kebede, the chief woman potter. She proudly told me that she had just started signing her name to her pots. She sold me several clay figures including a scarab like figure, and one of her trademark pots for cooking wat. She sent her little boy, Mellesot, back to town with me to carry my purchases. About half way home I thanked Mellesot, gave him five cents and sent him back to the village. At the edge of Gondar I met two students, Zerai and Alemu Asres. Throughout our two years in Gondar, students would not let us carry anything so they walked the rest of the way with me to my house, carrying my pottery.

My diary noted the arrival in 1963 of Dr. Daniel Harel and his wife Vered. They came to Gondar to work with the Falasha living around Ambover, a village south of Gondar. Vered was responsible for the establishment of a school and Daniel a health clinic in Ambover. Vered made Falasha handicraft items available to the large foreign community in Gondar in order to help finance the Ambover school. Later a man named David Zefrone (spelling?) came to Gondar to assist Vered with the school.

On June 5, 1964 I recorded this example of David Zefrone’s encounter with the Ethiopian Bureaucracy:

David Zefrone returned to Gondar, sputtering, after an exasperating week in Addis. He’s working for an international Jewish organization that is based in Geneva and he was invited to go to Geneva to report on what he’s been doing among the Falasha. He flew to Addis and asked for an exit visa at the Interior Ministry. They asked him for a paper from his employer in Ethiopia. He said he didn’t have any employer in Ethiopia. The Ministry then replied that he had to have an employer and then asked him what he did. He told them he taught the Falashas near Gondar. The Interior Ministry then said you must thus be working for the Ministry of Education and should bring a paper from Ato Yoseph in Gondar. He said he did not work for Ato Yoseph or the Ministry of Education. They then told him to go back to Gondar and bring a paper from the Governor saying that it is all right for him to leave. The Israeli Embassy even tried to intervene as his guarantor by guaranteeing his return to Ethiopia if he’d done anything unacceptable while in Ethiopia. The Ministry of Interior said no, so David returned to Gondar.

On March 26, 1964 I was invited to spend an evening with Arnold Toynbee, the British historian, at the Gondar Health College. Fortunately Toynbee delayed his visit a few days so I was able to accept the Harels’ kind invitation to attend Passover at Ambover:

At 5:30 Dan Harel stopped at our house to pick-up my housemate, Martin Benjamin and me. Dan then made a stop at the airport in an attempt to locate a package that was supposed to have arrived in Gondar. About five kilometers south of the airport, just past the bombed out Italian bridge, we turned north off the main Gondar/Bahir Dar road. The turn off point is a little sub-district village that contains an open air mill and about twenty huts scattered around a small market field. The women who live in the huts are all talla (beer) sellers. We then drove over a dirt track about 12 kilometers to the village of Ambover. Dan says that the first time he visited Ambover last year there wasn’t even a path and the trip took him four hours. Since then the villagers have cleared a path so the journey now takes only half an hour.

The Falasha who live near Ambover all rent the land they farm. The village is quite new as it was started only about 20 to 25 years ago when a large group of Falasha moved down from the Simien Mountains in order to avoid the Italians. The only buildings in the village are the health clinic, a school, a synagogue and a few steel roofed houses for teachers. The 3500 Falashas are scattered around on the nearby hills. We arrived in the village at about 7:00 so we quickly were shown about the school and clinic before it was completely dark. The school has been built by masons from Gondar and has been paid for by the Harels and their organization in Israel. David had a major hand in building the door frames, doors, windows, etc. Some students tried to carry a desk out of a classroom to take to the synagogue but they couldn’t because the desk was placed in the room before the door was installed.

Dan’s clinic was in a newly built building with woven reed mats on the dirt floor. He had an eye chart on the wall that was designed for those who cannot read. The chart was of limited use because the residents of Ambover do not recognize chairs, tables, stairs, etc. Dan’s assistant (Getachun) is a Falasha dresser (health worker) who Dan was fortunate to locate in Addis. The man was willing to return to Ambover where he built himself a house and married a local woman. Near the clinic is a large hole in the ground that Dan hopes will shortly become a well. Now the residents must bring water from a spring fed stream at the base of the mountain. The synagogue is just a small square building. When the Harels arrived the synagogue was roofless with an ostrich egg (a common Christian symbol) affixed to the top of the frame. The Harels paid for a new roof complete with a Star of David.

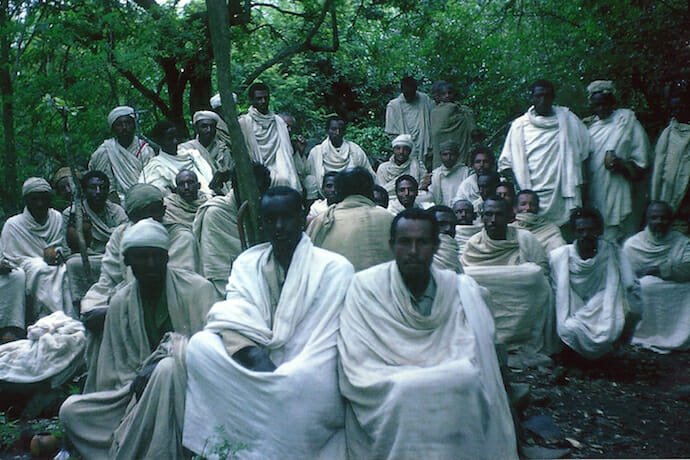

As the sun was setting beyond Lake Tana seven old priests stood inside the synagogue and chanted in Geez (the liturgical language for Christians and Jews). There are seven teachers in the village school. Because several have been educated in Israel they spoke with the Harels in Hebrew. Hebrew is taught to all the 250 students in the school. The request for permission to teach Hebrew was based on the same reasoning that Ethiopian Moslems use to teach Arabic in their schools. The Ministry of Education would probably not allow instruction in Hebrew to be taught if it were not a necessary part of the religion. The villagers have been drinking only water this past week. They have also only eaten newly prepared foods for each meal and have avoided the normal fermented injera.

Far in the distance we could see fires burning in huts. We sat on the ground and watched Venus appear in the southwest and the moon come-up over the mountain behind us. After the priests had chanted for an hour we all went into the synagogue where the Israeli educated youth read and chanted the Hebrew service. At first they were a little confused and were reading aloud the directions on how the table should be prepared, etc. Vered quickly straightened that out. The synagogue was lighted by two tiny locally made kerosene lamps. On one wall behind the priests was hung a long strip of colorful cloth. There must have been 300 people seated on the floor. Most of them seemed to be able to follow the Hebrew.

I recorded the service. However, several years ago I loaned the tape to a doctor in Chicago to enjoy for Passover and it was never returned:

Sometime after 9:00 we all left the building and sat on the ground outside. Over a dozen injera baskets of matzo were brought by children. The bread was blessed in Geez and Hebrew. It tasted like the usual “dabbo” (wheat bread) except it was flat like injera. The Geez prayers that are chanted are from the Falasha Book of Prayer. It is said that there remains only one copy of the book and it is in Simien. The school children next sang a number of Israeli folk songs. The priests repeated some more Geez prayers that were translated into Hebrew for the benefit of the Harels.

We were impressed with how clean the children were. The children did not have flies around their eyes. Dan said that is probably due to the Monday morning inspections held at the school each week. The cleanest student always gets a special bar of soap. On the drive back to Gondar, Dan talked about the problem of the old religious leaders not being replaced. Their children who would normally take on the responsibility, now want to become teachers. I asked Dan if any of the Falasha ever have contact with the Debra Tabor or Dabat Christian missions. He said it is something of a joke among the Falasha. Some may use the mission for a while and then go back to being a Falasha. In his twenty or so years in Ethiopia Rev. Payne has succeeded in converting one Falasha religious leader to Christianity at the mission. Dan said that Payne keeps the man around the Dabat mission like a trophy. The Falasha refer to Passover as Fasika (Easter in Amharic).

As a footnote to this short “tarik” about the Falasha I’d like to relate my conversations with Sister Lena who was a German Anglican nun at one of the two missions. The missions were started in the 19th. century to convert the Falasha to Christianity. About four times during my two years in Gondar I met Sister Lena while she was visiting Gondar. Our longest conversation occurred on June 19, 1964 on the plane from Gondar to Addis. It was the start of her final flight back to Germany where she planned to retire and for me and sixty other Peace Corps volunteers it was a summons to meet with Ambassador Edward Korry at the Embassy for an update on American activities in Ethiopia. Sister Lena first came to Ethiopia in 1932. She said it took her six weeks by mule to reach Gondar from the coast.

At that time Gondar consisted of ruined castles and mud houses. In November 1935, with the Italians approaching, Sister Lena and the others at the mission fled by mule to the Sudan and there they took the train to Port Sudan in order to board a ship to England.

They all contracted malaria while crossing the lowlands between Gondar and the Sudan. Sister Lena returned to Ethiopia in 1952. She acknowledged that the Falasha couples who live at the Debat mission continue to maintain their unique Falasha traditions.

***

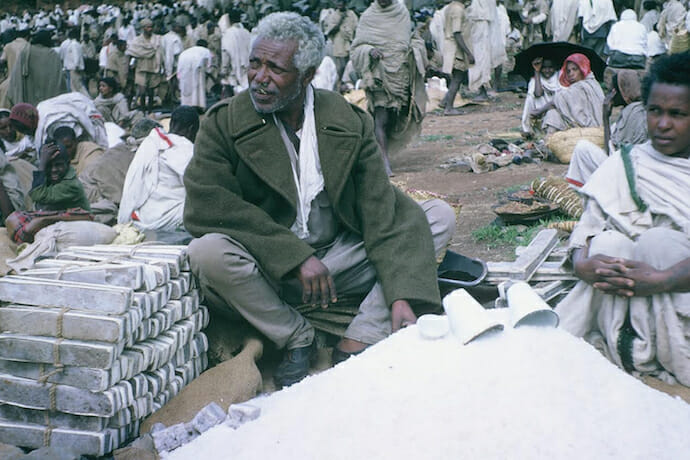

Part 6. The Gondar Market

During our Peace Corps stay Gondar was an important market town for much of Begemedir Province. The overwhelming majority of residents of the town and countryside met their daily needs by participating in the weekly Saturday market. The market was attended by thousands of people and took place on a large stony field about two miles from our house.

On Saturdays when I wasn’t busy supervising students tending their gardens at the school I would enjoy visiting the market. I was there often enough so vendors knew me and were comfortable with my photographing them at work. Early each Saturday morning farmers and their families from the south and west of Gondar would pass our house with donkeys laden with grain sacks made from sheep skins. One photograph is of a group of farmers passing the tomb of Zobel, the favorite horse of Emperor Fasilides the Great (1632-1667). This monument, located only a few hundred yards from our house, was my favorite of all the historic buildings of Gondar.

Another photo shows a woman on her way to market balancing an empty sheepskin sack on her head (she probably intended to fill it with gesho leaves which she would use to make talla beer). On her back is a baby in a carrier. In her left hand is a colorful chicken which she was selling and in her right hand was the ever present black umbrella.

On March 30, 1963 I wrote the following after visiting the market:

One of the most unusual items for sale in the market is the Ankalaba, a large tanned leather sheet which women use to carry children on their backs. Men always buy one for the child’s mother. However, they wait a few weeks after the child’s birth to determine if the child will live. The price for an ankalaba is 4 shillings or $2 Eth.

Many sheepskin bags full of gesho leaves for talla making were on sale. Gesho is the dried green leaf which acts as would hops in beer making. A large leather sack full of gesho (about a bushel) cost $1 Eth.

On a high place in the market under the worku tree were hobbled hundreds of donkeys. Some had open sores on their backs. With the mother donkeys were their young who had followed along on the market journey.

John Stockton was with me as we worked our way through the market buying limes and eggs. We’ve always felt very comfortable and safe in the market. As we were standing near the berberi (pepper) saleswomen a young man tried to pick John’s pocket. John punched him hard enough to knock him to the ground. The young man jumped up and took off running. All around us we heard the Ethiopian startled response of “aarah, aarah” followed by shouts of approval of John’s bold action.

In the afternoon several of us borrowed some of the school’s new American baseball equipment and had a pick-up game of baseball on the sports field next to the Zobel monument. Soon there was a crowd of about 100 watching, including two priests sitting out in left field near the monument. Every once in a while we had to stop the game to let a train of donkeys pass on their way home from the market.

Very late in the afternoon Mr. Ooman (Assistant Headmaster) asked Marty Benjamin and me to join him and go to Azozo (the army base a few miles south of Gondar). The purpose of the trip was to measure the heights of students in preparation for the upcoming sports competition. We were chosen to help because we had no vested interest in the outcome of the sports competition. It would be impossible to group students according to age because their birth date in often unknown. In the Azozo school yard were several hundred little squirming students we had to stand up against a wall and group according to height. The Azozo school is quite good as most of the parents are with the army. We’ve heard that about half of the Azozo troops are now serving with the U.N. in the Congo.

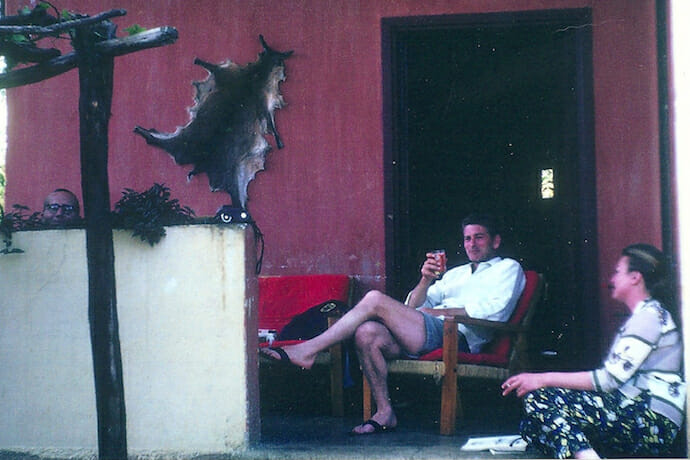

On April 27, 1963 Andrea Wright invited all of the other eleven Peace Corps Volunteers to her birthday party. The twelve of us lived in three separate houses. John and Peggy Davis had their own house next to the school. Martin Benjamin, John Stockton, Dallas Smith and I shared a house across from the school. Jack Prebis, Charlie Callahan, Frank Mason, Andrea Wright, Trish Martin-Jenkins and Madelyn Engvall had a compound about a half mile away from the school:

Andrea served anchovies, cream cheese, shrimp hors d’oeuvres and Scotch, teg (honey mead) and soda. For dinner we had hamburgers, salad, zucchini and cake with ice cream. After dinner we all sat around and talked for the first time in many months. The three women have a mini farm behind their house with a chicken house full of multi-colored chickens, a pig, a baby donkey, a ewe with a lamb, two horses and a cat. The best story of the evening was about the acquisition of the donkey. Andrea and her housemates asked several students to go to the Saturday market to buy a baby donkey. At the market the students were confronted by very suspicious farmers who did not understand why foreigners would want to buy a baby donkey. The creative students improvised a story that these women were part of the Peace Corps (Salaam Guad) and were trying to show that all these animals are able to live in peace and thus so should people. The students were very convincing because the returned with a donkey.

Of the twelve of us Dallas Smith was the only one who had inherited the “bargaining gene.” If I ever needed to buy something important in one of the shops near the market I would enlist Dallas’ help and then stand back and watch his performance with awe. Dallas would approach the merchant with all the proper friendly greetings and respect. After asking the price of the object, which was always too high, Dallas would begin to flap his arms and shout “Leba! Leba!” (thief, thief) and threaten to leave.

Within minutes the merchant and Dallas would have agreed on a price and Dallas would be found seated with the merchant behind the counter drinking tiny cups of very strong black coffee. Dallas’ bargaining skills were on display in other ways. At 6:00 P.M. on the days the airplane landed in Gondar, the mail sacks would be opened on the Post Office counter. Across the counter from the clerks sorting the mail, noisy rude foreigners would clamor for their mail.

Dallas had cultivated the postal clerks and treated them with respect, even, at times, bringing them coffee, so they would take special care with our mail. That even carried over to sending packages home. If Dallas mailed our packages the cost was always reasonable.

During the Orthodox Easter fast of 1964 there was no meat available in Gondar for six weeks. Cattle were not for sale and no animals were slaughtered. Somehow, Dallas arranged for a cow to be killed in his yard in the approved Orthodox manner and had the meat divided among seven households.

Dallas captured the whole bloody event with his movie camera. Because he always sent his film home for his mother to develop and show to her friends he could imagine the scene in Winslow, Illinois when the ladies were innocently shown the movie.

At the end of the Saturday market day the farmers would pass my house on their journey home. I enjoyed sitting on my porch watching the parade. Sometimes the young men would sing bawdy songs as they walked along and if they had had a very good day at the market and maybe enjoyed too much talla in a talla bet (beer house) they would playfully foot race their donkeys past Zobel’s monument.

***

Part 7. My Home in Gondar is Now a School

When we arrived in Gondar, Ethiopia on September 21, 1962 we were assigned to houses rented by the Peace Corps office in Addis. John Stockton, Dallas Smith, Marty Benjamin and I were given a house on a hillside surrounded by several acres of fields across from the school. The house was enchantingly reminiscent of a Joseph Conrad novel. It was of frame construction set on a massive elevated stone foundation. Each of the four rooms had louvered doors opening onto a veranda which surrounded the entire house. The metal roof added more to the mystique, especially during the rainy season when the sound of the intense rains made being heard difficult.

The house had been built by an Italian engineer for his own use during the period of Italian occupation of Gondar (1935-1941). By 1962 the ownership of the house was murky at best. A man who called himself the “landlord” would appear at our door but we suspected that he was an agent for some important person or government body that had taken ownership after the war.

The Peace Corps paid the $110Eth./month rent ($44 dollars) directly so we never knew who received the money. However, we were summoned into court throughout the two year period over numerous ownership disputes. We sensed that there was a badge of honor attached to an Ethiopian for bringing a matter before the court.

Originally the house had a bathroom, so as part of the lease the “landlord” was charged with restoring it. In the rafters of the house were two large concrete tanks which were regulated by floats and stored water which flowed through the town water pipes. Throughout October we battled with the landlord to complete the work.

The workmen he sent confided in us that he had a history of not paying his workers and not finishing jobs. We got his attention on October 6 when he came to inspect the leaky sink, loose/leaking toilet bowl and bathtub that was not hooked into the sewer line to the septic tank. He was standing close to the toilet when John reached up and pulled the chain on the toilet flush tank. As we anticipated, the leaking toilet poured water over his fancy Italian shoes. Ultimately we gave up and paid the plumber from the hospital to moonlight for a few hours to do the job right.

A small white dog appeared at our house, as if asking for a place to stay. Because she was so pregnant one of our students named her Sintayu (I have seen too much). We adopted her and although she was friendly she would bark at visitors in a non threatening way. We developed the impression that she might be a racist because she only barked at our Ethiopian visitors . However, Marty put forth a very plausible theory to explain Sintayu’s behavior. Marty observed that Sintayu only barked at visitors who were not wearing shoes.

As the dry season intensified there was an influx of rats seeking water and a source of food. Out bathroom was the focus of their attention. They would climb down the pipes from the attic and crawl up other pipes from the basement. As we were working on our lessons and papers we would hear the clanging of the steel traps we had scattered around on the floor. On December 12, 1963 my diary noted that in one trap we caught “two rats at one time.”

Late in the dry season during the months of March and April, at the start of the small rains, we were accosted by an invasion of moths and unique flying worms. The worms were large and numerous and were attracted by our study lights. We became very practiced snatching them out of the air.

Water was brought to our house through the town water system. Because the pipes were often above ground and subject to leaking we did not drink the water without first boiling it. As the dry season ended and the small rains began, the water would be shut off for days at a time. Before the rains started we would try to take the precaution of having out bathtub full of water. Once the rains began we could catch enough water from the roof to meet our needs.

Many residents of Gondar could not afford to get their water from the town system. They depended upon women to deliver water which they would carry in heavy earthen jars on their backs. The water carriers would fill their jars from the nearby Oaha River. As the dry season continued the river would almost dry up. As the women took a short cut walking through our compound passing our front door, we would listen to the musical sound created by the floating metal cans used for dipping as they clanged against the sides of the earthen jars. By hiding my tape recorder near my front gate I captured a recording of the water carriers’ symphony.

Dr. Rossa, the American director of the Gondar Hospital stopped at the house on October 14, 1962 and invited us on an inspection tour of the Gondar water collection system located in the mountains about 10 km. north of Gondar. There pipes ran from several small mountain streams and then the water was collected at a central little stone building from which it was sent through a larger pipe to Gondar. There was a large unopened bag of chemicals in the building but there was no evidence that the water was treated in a systematic way. Near the water system was the road to the Sudan which is passable (barely) in the dry season. Dr. Rossa related that herds of elephants and hippos in the lowlands between Gondar’s 8,000 foot elevation and the Sudan can be seen only during the rainy season.

After touring the water works, Dr. Rossa took us to his favorite swimming hole in one of the mountain streams. Because no one lived in the area he expressed confidence that the risk from shistosomiasis/bilharzia (liver flukes) was minimal. He did, however, advise us to never swim near the shore in Lake Tana, the source of the Blue Nile, because infected snails inhabit shallow water.

The swimming hole was a delightful refreshing pool trapped beneath where the mountain stream formed a waterfall. As we were enjoying ourselves a puzzled Ethiopian farmer walked by and peered down at us.

Six years ago my son, John, accompanied me on my first return visit to Gondar. Of course, I wanted to show him my old house. The formerly spacious field around it is now filled with countless new houses, but my old house still stands. It and a building constructed next to it now house the Rekebnaha Kindergarten and Primary School, a 600+ student private school. The Headmistress of the school, Rekebnaha Geremew, welcomed us to the school and we toured each of the classrooms. The dirt basement has been excavated and is now a resource center with computers.

It was very touching to see the 50 eager young students studying in my old room. Close to 100 of the students in Rekebnaha School are orphans who attend without paying school fees. The school can be contacted at:

Rekebnaha Kindergarten and Primary School

P. O. Box 111

Gondar, Ethiopia

After touring the school I was reminded of a comment made by one of my students, Teshale Berihune. On July 20, 1963 Teshale visited my house in order to borrow several books from our Peace Corps footlocker library. At the time only Marty Benjamin and I were living in the house. Teshale commented on how strange it was for just two people to live in such a large four room house. He said: “Mr. Lyman, this is a house, not a village.”

Today my old house, hosting hundreds of students, has indeed become Teshale’s “village.”

***

Part 8. Our Wonderful Cook, Aragash Haile

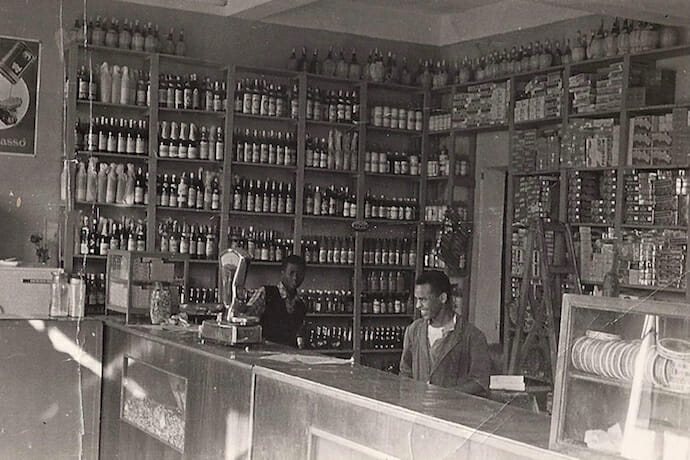

Marty Benjamin, John Stockton, Dallas Smith and I who shared a house in Gondar had the naïve notion that we were going to be self sufficient and live without servants. Little did we realize that in Gondar servants had servants. It took us several months to put aside the quaint notion of complete independence and hire much needed help. The fact that of the four of us only Dallas liked to cook should have been a red flag from the start. Within a week we opened a charge account at Ato Ghile Berhane’s “Ghile’s Store.”

It was a wide glass fronted store just around the corner on the Asmara road from the post office. Behind a tall counter were two engaging young men who would retrieve what we wanted from the floor to ceiling shelves. Our bulk purchases like rice and pasta were poured into cones formed from used Swedish newspapers. We were intrigued by the sight of several boxes of Kellogg’s Corn Flakes on the top shelf off to the left side of the store. We never asked who requested them and the cereal was still there two years later. Each item we purchased was written down in our account book and once a month Marty, who acted as our household “minister of finance,” would settle the account.

I saved the two account books from those two years in Gondar and suspect that someday an anthropologist studying the eating habits of Peace Corps volunteers will find it a gold mine of information.

The Peace Corps supplied us with a kerosene refrigerator and a kerosene stove. A problem was that frequently there was a lengthy shortage of kerosene. The two sources were Besse & Co., an Empire wide trading company, and the local AGIIP station. Whenever a supply would arrive by lorry from Asmara word would quickly spread and we would buy a number of tins.