Books

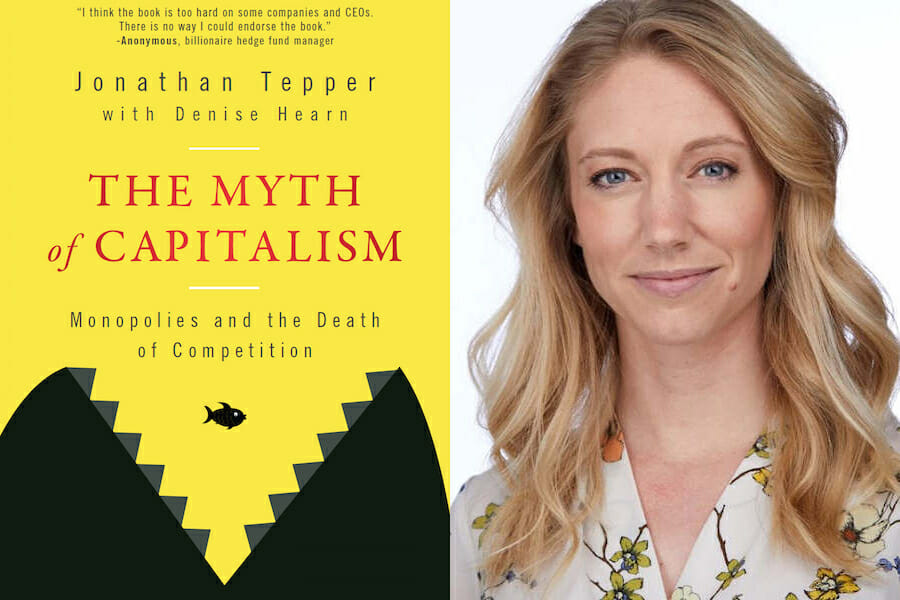

Denise Hearn on the Future of Capitalism

Our interview with author Denise Hearn, the head of Business Development at Variant Perception, a global macroeconomic research and investment strategy firm. Her new book is The Myth of Capitalism.

You write that American capitalism is a myth. How would you label the US economy?

American capitalism is a myth because the competitive free markets we associate with capitalism are a myth in today’s economy. Instead, we have an economy dominated by monopoly and oligopoly firms who can use their economic power to exert influence over regulators and politicians. Most Americans, 71% in fact, believe the economy is rigged and in many ways they are correct.

Will it be necessary to decline to bail out banks and corporations that go bankrupt in the inevitable next recession? Many people have argued that the 2008 bailout just made the US economy more vulnerable to future shocks.

The bailouts and the accompanying new regulation (Dodd-Frank) only further entrenched the ‘too big to fail’ banks. Glass-Steagall was 35 pages and Dodd-Frank is 2200. Most smaller banks cannot comply with that burdensome regulation, and so you have Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan, now stating that we’re in a “Golden Age of Banking.” No new entrants can come in and compete.

Credit unions and small banks do 60% of lending to small businesses, so you’ve also seen a decline in small businesses starting in the US as their lenders have disappeared, swallowed or put out of business by the major banks. Five banks now control half the nation’s banking assets. Additionally, when you lose localism and diversity, the entire economy suffers. Like monocropping in agriculture, loss of diversity means more susceptibility to shock, and we are certainly in that state today in the economy – not just in the banking industry.

Similarly, it seems to me that the rise of passive investing is leading to further self-perpetuation of the economic status quo by relying on the slow, steady gains of oligopolistic companies. What are your thoughts on passive investing?

I fully agree. Even Jack Bogle came out with an article recently stating that he’s concerned about the dominance of passive investing – the very financial innovation he created. Passive investing has been a great boon to American investors, but now you have a handful of oligopolistic firms (Vanguard, BlackRock, StateStreet) that control access to the passive products. Those big 3 own nearly 19% of the S&P 500, and passive funds now own 40% of all US assets. So it’s like an oligopoly layer cake where oligopolistic investors invest in oligopolistic industries.

What are your thoughts on natural monopolies? Can Google be considered to be a natural monopoly?

Natural monopolies are rare and necessary only in very specific industries like aerospace manufacturing. Google controls 90% of search, but it did not get here simply via innovation. Google, Facebook, and Amazon have great technology, but much of their current status and financial success comes from regulatory and antitrust mistakes. Amazon was allowed to buy dozens of ecommerce rivals and online booksellers to give it a monopsony position in the book industry. Google was able to buy its main competitor, DoubleClick, and vertically integrate online ad markets by buying advertising exchanges. It also scraped loads of data from Yelp, Getty Images and multiple other companies to build its search interface. So no, Google is not a ‘natural’ monopoly.

Should stock buybacks and corporate spending on election campaigns be outlawed, like they were pre-Reagan?

Stock buybacks are symptomatic of larger issues. Corporate profits are at record highs, and companies need to invest their cash somewhere. The explosion in buybacks is symptomatic of sky-high profits that are not mean-reverting, due to the solidified market power of oligopolistic firms. Although, US corporates are on a spending spree with plans of $1 trillion worth of buybacks this year, according to a recent FT article.

Rather than outlawing buybacks, I think some useful limitations could be instituted. Like, for instance, preventing CEOs and corporate insiders from selling their stocks during (or within a reasonable time frame after) repurchasing programs.

How should executive pay be restructured to eliminate perverse incentives for executives to mortgage a company’s future in the name of short-term gains?

In the 1970s, CEO-to-worker compensation was much more level with many other countries around the world today (about 30:1). That number has skyrocketed to 361:1 in the United States. Managers should certainly be compensated for the difficult work they do, but it is hard to believe CEOs, as a group, are now ten times more valuable relative to workers than they were in the 1970s.

Part of the issue is that, originally management pay was determined according to “internal equity.” A manager’s value to the firm was determined by his or her performance relative to other employees. In the 1970s, with the rise of executive compensation consulting, the focus shifted to “external equity” – or comparing CEOs to what others were being paid across the industry.

Boards and compensation committees agree to compensation packages based on benchmarking against other comparable companies, but they are all benchmarking against each other in a never-ending infinite loop of salary increases. Studies also show that the companies that serve as benchmarks are always chosen to maximize CEO pay. Returning to a focus on internal equity would be a start in reforming.

The financial stability of the antitrust enforcement era coincided with the peak power of the trade union. Can a renewal of unionization reverse the fortunes of the average American worker?

Workers today are dispersed and have very little bargaining power. Unionization has collapsed, and according to one study by Katz and Krueger (Princteon and Harvard economists) almost 100% of the jobs created since the Financial Crisis are temporary. Workers need some kind of countervailing force, especially in the wake of the stunning consolidation of corporate power we’ve seen in recent decades.

Strengthening union participation would certainly help, but other measures that give workers power like including them on corporate boards, as Germany does, in co-determination agreements, or making them owners of capital via ESOPs are other ways to restore power to American workers.

Do you think the US should adopt an ordoliberal economic model or a Scandinavian social-democratic economic model?

Either would be an improvement on our current state of affairs. As a Canadian living in the US and married to an American, I now appreciate to an even greater degree elements of Canada’s social-democracy like socialized healthcare.

Ordoliberalism argues that capitalism requires a strong government to create a framework of rules that provide the order that free markets need to function properly. The ordoliberals thought state intervention through antitrust was an essential ingredient to make markets function, and I would agree with this perspective.

What do you make of the unprecedented success of China’s system of state capitalism?

Capitalism has been a global success in many ways when you consider that it has lifted billions out of poverty and created vast wealth and high standards of living for millions around the world – China included. I don’t feel qualified to make a statement on China’s version of capitalism, but we do write about some of the new tactics of command and control that state is using to monitor citizens in the book, like the social credit system. Americans are shocked to learn of the implementation of the credit system, but we have abdicated just as much information (likely more) to the private entities/tech giants. Google and Facebook have more information on us than the Stasi ever had on citizens in Germany. We seem unperturbed and continue using our devices.

How would you respond to the argument that capitalism has, from its roots as the Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company, mainly succeeded due to slavery and colonialism and that the decline of Western capitalism started alongside the era of de-colonization and the death of Jim Crow?

This is a big question and one that I would want to spend much more time researching before providing a definitive claim. There is, however, no doubt that systems of power and privilege have exploited people of color the world over, and continue to do so today. My work on this book is motivated by a desire to create systems with opportunity for all, and I sincerely hope that this is one small step in that direction.

You write a lot about how US healthcare companies are price-gouging Americans, to the tune of trillions. Do you think Medicare for All is a good policy solution for the only industrialized nation without universal healthcare?

I’m not a healthcare expert by any means, so I won’t make a comment on what the US should or should not do regarding single-payer systems – there are multiple iterations of what that can look like. I will say, that endlessly extending patents on slightly reformulated drugs or not approving generics (there is currently a backlog of over 4,000 at the FDA) has greatly hurt the average American and caused insane price gouging to occur, as you mention.

How do you envision the future of capitalism in the coming era of automation?

Workers had similar fears of obsolescence during the Industrial Revolution, but with new technology come the creation of new jobs. I think we will likely continue to see the creation of jobs we have yet to conceive of in coming years. People tend to overestimate the effects of automation on the job market, and to look to the past with nostalgia and the future with trepidation.

100 years ago most humans were employed as farmers, and globally now only 2% of the population are farmers – and we don’t have 98% unemployment. There are multiple examples like this when we think of advancements in technology and the labor market.

A more pernicious and immediate threat than automation, in my opinion, is labor monopsony from dominant firms. Ask Amazon fulfillment center employees who are likely most at risk of losing jobs to automation. If we don’t materially reduce the corporate ascendency of mega firms, the worker’s next contract job may entail even worse wages, conditions, and benefits. And that’s saying something, considering how bad those Amazon jobs are.