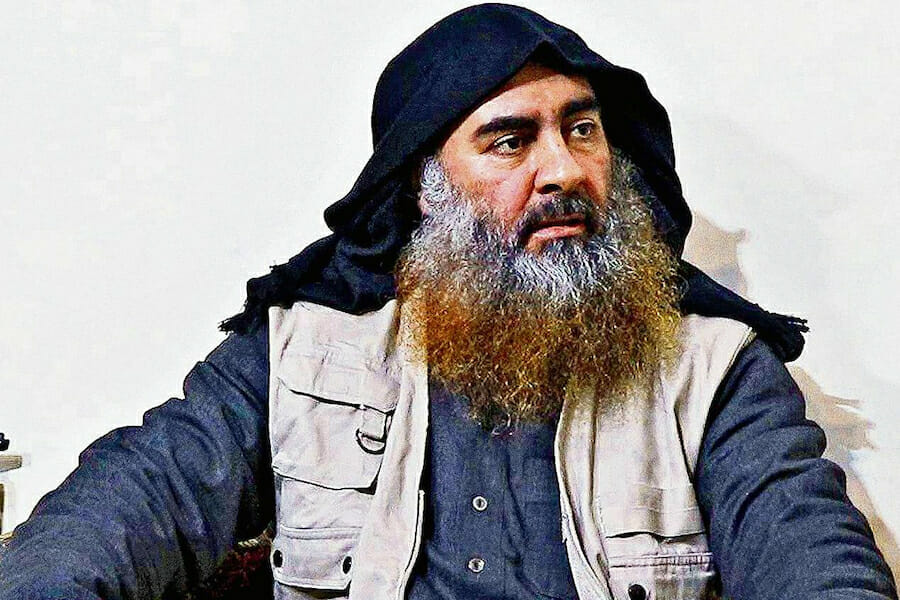

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi Relinquishes Control of ISIS, but not the Islamic Caliphate

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the ruthless commander of ISIS, has named a successor to replace him at the helm of the terrorist organization, Abdullah Qardash of Tal Afar, a predominantly Sunni Muslim city in northwestern Iraq. The appointment was announced on 8 August, via ISIS’s semi-official news agency, Amaq. It came as little surprise to jihad-watchers across the globe, given Abu Bakr’s deteriorating health since his most recent recorded address in April, he is believed to be suffering from limb paralysis—according to the Iraqi Ministry of Interior—sustained from shrapnel wounds inflicted during ISIS’ last battle in Hajin on the Euphrates River in Syria.

What many failed to grasp was that Qardash’s designation was to replace Baghdadi only as commander of ISIS and not the self-proclaimed caliphate of all Muslims, a post that Baghdadi had assumed back in 2014. That remains exclusively in the hands of Baghdadi—at least for now—and he won’t be relinquishing it to anybody, anytime soon. When Baghdadi proclaimed the caliphate five years ago, ISIS spokesman, Abu Mohammad al-Adnani described it as a “dream that lives in the depths of every Muslim believer.” “The legality of all emirates, groups, states, and organizations becomes null by the expansion of the caliph’s authority.” In other words, with a single verdict, he rejected all other Islamic groups as invalid, giving him great powers across the entire Muslim world. The declaration was sharply criticized by Islamic scholars worldwide. Most weren’t critical of the concept, but of the person himself, claiming that Baghdadi did not have the religious credentials needed to assume such a title.

A brief history of the Caliphate

The last Muslim caliphate had been that of the Ottoman sultan, which was abolished by Kemal Ataturk in Turkey, back in 1924. During World War I, the Ottoman caliphate had dwarfed into a semi-symbolic and a very lightweight religious authority. By the early 1920s, gone was the pomp and power vested in the person of the Ottoman Sultan, whose army had been crushed and whose empire lay in ruins. Once commanding wide respect reaching as far as Muslim Spain and India, the defeated caliph was now forced to obey the dictates of Great Britain and France, who laid siege to his capital. On 17 October 1922, the last caliph left his throne in Istanbul, aboard a British liner headed to Malta, with orders never to return. He never did, and neither did the caliphate of Islam as the world knew it.

Some of Ataturk’s aides had advised against abolishing the caliphate, claiming that it could be separated from the sultanate, and thus maintained. Doing away with the sultan’s divine authority was one thing, but abolishing a title once held by Mohammad’s companions was something totally different. They argued that keeping the caliphate would serve the interests of the new Turkish republic, uniting the world’s 15 million Muslims worldwide behind its authority. It would be similar to the Vatican’s hold over Catholicism, they argued. The staunchly republican and secular Ataturk, however, had different plans for Turkey, a caliphate strongly contradicted with republicanism, he said.

Muslims around the world, former subjects of the caliph, were unhappy with Ataturk’s decision. Many tried to save the caliphate from collapse, with little success. In 1919, for example, the Khalifat Movement of India was created to lobby global Muslim support against Great Britain, attracting senior figures to its events, including Mahatma Gandhi. It was short-lived and unsuccessful, as were other bids for the caliphate. In Damascus, a caliphate movement was established by the Algerian notable Emir Said El Djezairi, but it too died out by the late 1920s.

The issue was hardly forgotten in the century that followed. The Muslim Brotherhood, founded in Egypt in 1928, called for the restoration of the caliphate. In 2007, for example, a Gallup poll found that 71% of respondents from four Muslim countries wanted the laws of Islamic Sharia to apply in every Islamic country. They were of different age groups and backgrounds, coming from Egypt, Morocco, Pakistan, and Indonesia. Additionally, 65% wanted unity of Muslim states under a caliphate and 74% wanted to keep Western values out of Islamic countries. Also, that summer 100,000 people filled the main stadium in Jakarta to “push for the creation of a single state across the Muslim world.” In mid-2006, Osama bin Laden called Baghdad the “home of the caliphate.”

When asked by British journalist Robert Fisk what kind of system he would like to live under, bin Laden replied that it was obligatory for all Muslims to establish “an Islamic State that abides by God’s laws.” He only started using the term “caliphate” more frequently after the 2003 Iraq War, hoping to galvanize Muslims across the world. In 2006, U.S. President George W. Bush mentioned the caliphate 15 times, including four times in a single speech. U.S. Vice-President Dick Cheney warned that al-Qaeda wanted to “re-create the old caliphate,” while Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld added that al-Qaeda wanted “to establish a caliphate instead of mainstream Muslim regimes.” In August 2011, U.S. Representative Allen West added, “This so-called Arab Spring is less about a democratic movement than it is about the early phase of the restoration of an Islamic Caliphate.”

A null caliphate

Yet it was ninety years after Ataturk that the first serious contender for the “Caliph” emerged. Rising from obscurity, Ibrahim Awad Ibrahim al-Badri aka Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, declared himself as the new caliph of Islam, using the name “Abu Bakr” in reference to the first successor of the prophet, Abu Bakr al-Saddik. Entire chunks of his famous 20-minute video in Mosul were ripped out of one of Saddik’s speeches, memorized by heart by Muslim worshippers. Many were critical of the declaration, including Baghdadi’s former protégé, Abu Mohammad al-Golani, then commander of Jabhat al-Nusra, now renamed Hayat Tahrir al-Sham. He said: “Abu Bakr is a usurper. Even if he were to declare the caliphate a thousand times, no one must be deceived.”

On 20 September 2014, over 120 Sunni clerics from the Sufi order signed an open letter to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, challenging his interpretations of the Holy Quran. “You have misinterpreted Islam into a religion of harshness, brutality, torture, and murder,” they said. “This is a great mistake and an offense to Islam, to Muslims and to the entire world.” Yet despite these loud voices, Baghdadi went ahead with his caliphate, with one success after another. At its apex, the ISIS caliphate controlled an area stretching across 90,000 square meters, covering the deserts of Syria and Iraq, with a total population of 6 million people. Affiliate groups mushroomed across the world, pledging allegiance to the caliph in Libya, Egypt, Nigeria, and deep within the cities of Europe and the Far East. At one point in time, he had all the trappings of statehood: a full-fledged army with up to 50,000 fighters including thousands of foreign jihadis, a ruthless intelligence service, a network of schools and hospitals, a media agency, a national flag, and a treasury loaded with oil money. Despite the brutal tactics that he carried out, which included head-chopping and burning people alive, people kept flocking into his “state.” There was something appealing about Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi that people genuinely liked. It was his job title. He really believed that he was the caliph of Islam. Some people apparently really believe him.

Qardash’s chances at the caliphate

In the Quran itself, the word “caliph” appears three times. According to Sunni jurisprudence, the caliph must be able to trace his lineage directly back to the Quraysh clan of Mecca, to which the Prophet belonged. Shiite Muslims claim that being a Mecca notable by ancestry is not enough to become caliph, saying that potential contenders need to hail strictly from Ahl al-Bayt, the family of the Prophet. This explains why Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi insists on using two important additional last names whenever making a public statement or appearance. One is al-Qurashi, hailing from Quraysh and another is al-Hassani, the descendant of the Prophet’s grandson. Western journalists and non-Muslims tend to drop both titles for practicality, but ISIS media never refers to him without both affiliations. Al-Baghdadi wants to draw as much historical, religious and popular legitimacy as he could; yet this should not be seen as an attempt to placate either the Shiites nor the Sunnis who oppose him. Interestingly, Abdullah Qardash also hails from Quraysh and from Ahl al-Bayt, makes him an eligible future caliph, should Baghdadi decide to bequeath power to him, or should he assume it himself, with or without Baghdadi’s consent. Apart from lineage, conditions for becoming a caliph are fairly straightforward and also apply to Qardash. The caliph must be a Muslim male, is required to lead the masses during prayer and prove knowledgeable in Islamic jurisprudence and history, two traits that also apply to Qardash, a former Iraqi officer under Saddam schooled at the College of Imam Al-Adham Abu Hanifa al-Noueimi in Mosul.