Turkish Kurds and Presidential Politics

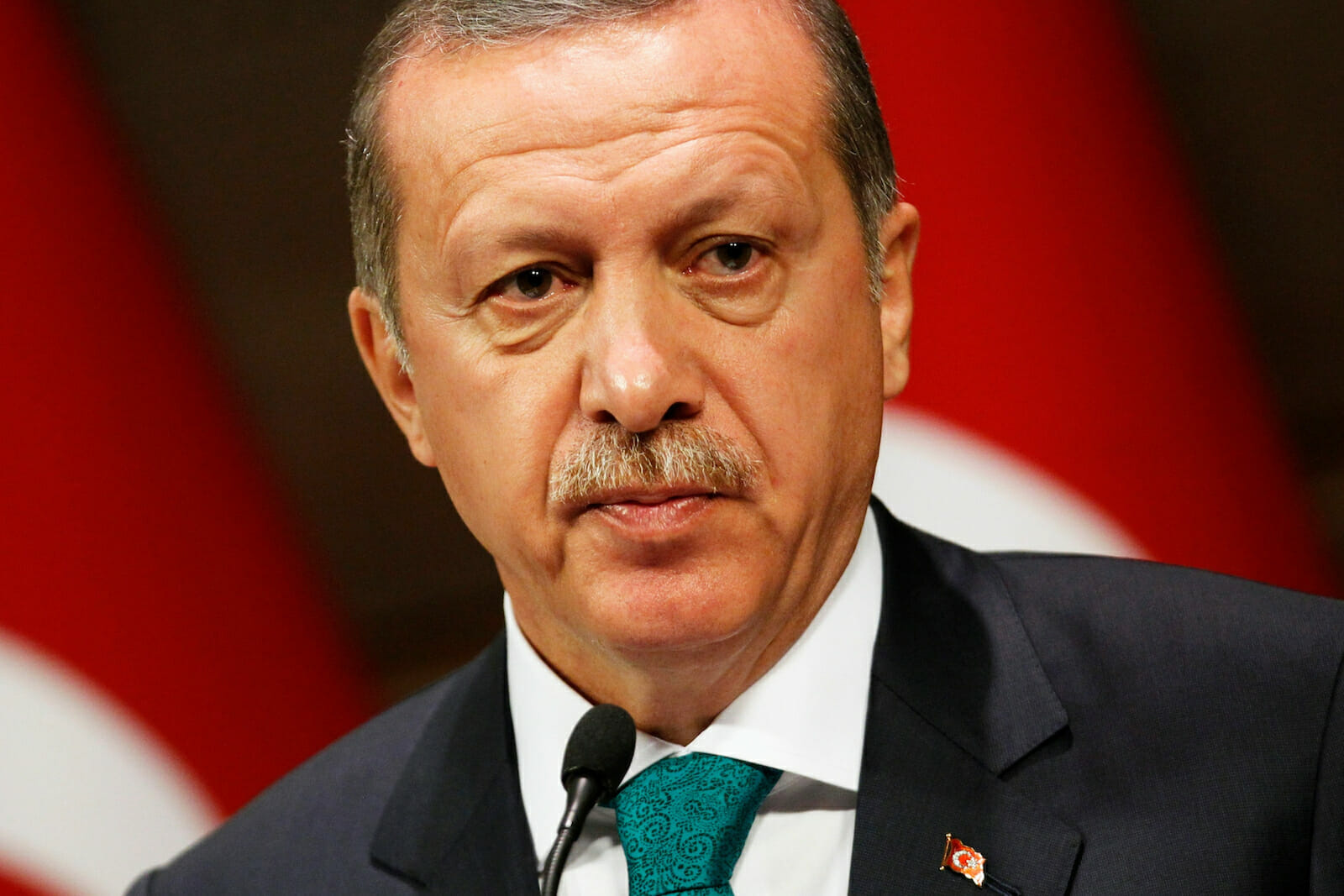

Late last week, the Turkish government submitted a bill to the Grand National Assembly advancing the stalled-but-ongoing process toward resolution of the country’s longstanding Kurdish Issue. The bill arrived after a long period of dormancy in the process. Since the negotiations with jailed PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan began, Prime Minister Erdoğan has faced mass social protests, corruption allegations, and contentious local elections.

The government recommences the process at a time when Iraq is melting down and the Turkey-KRG relationship looks stronger—and more elemental—than ever. This fact has not escaped commentators on the bill. The Wall Street Journal reported on the new bill and implicitly connected it to Turkey’s relationship with increasingly important relationship with the Iraqi Kurds.

That explanation is a bit too neat and elides some of the complexities—both in the bill and in the Turkey-KRG relationship. Hurriyet Daily News published a nice summary of the bill’s contents. The bill is mostly procedural. It sets out government control of the process and its reporting mechanisms. Only two articles appear ripe for analysis.

First, the bill explicitly grants targeted legal immunity to any government appointees tasked with negotiations on behalf of the Turkish state.

If Erdoğan’s purges in the judiciary and police force were not enough, this article represents another swipe at the Gülen Movement—which has generally opposed negotiations with PKK insurgents as part of a solution to the Kurdish Issue.

In 2012, Gülenist prosecutors sought to bring criminal charges against intelligence chief and top Erdoğan adviser Hakan Fidan. Erdoğan countered by ramming through immunity from prosecution for Fidan. The immunity article formally extends protection to anyone involved in the negotiations and is nothing more than a preemptive step to discourage Gülenist machinations.

Second, the government—in a very preliminary fashion—has launched the process of bringing PKK fighters down from the mountain and reintegrating them into society. This is a commendable—if long-overdue—step from Erdoğan, and any optimism about the process is pinned to this article. Some analysts may see this genuine step forward as motivated by the crumbling of Iraq.

We should avoid the temptation to connect this step to the ongoing Iraq crisis. As a factual matter, the AKP government advances this bill at the same time as its relationship with the KRG evolves precipitously. But the two are not necessarily related. Turgut Özal famously viewed relations with the KRG as a powerful antidote to Turkey’s Kurdish Issue. In response to Kurds in Turkey clamoring for a state, Özal believed Turkey could strengthen its position if it could point to a self-governing Kurdish region in Iraq. Relations with the KRG would not facilitate a solution, they would obviate the need for one.

Moreover, the KRG’s relationship with the PKK—as with so many intra-Kurdish group relations—is complex. The KRG has not worked especially hard to oust PKK fighters from the Qandil mountains in Iraqi Kurdistan. At the same time, Barzani cultivated the Turkish relationship well before the Kurdish Issue solution process began. Since the Syrian civil war loosed the Syrian Kurds from centralized control, Barzani has worked to expand KDP influence—opening low-intensity conflict with Salih Muslim, leader of the PKK-aligned Syrian Kurdish PYD.

Finally, in a mildly surprising departure from the AKP’s usual lockstep messaging, debate has bubbled up from the circle around the Prime Minister. Hüseyin Çelik, former Education Minister and Erdoğan’s close ally, said recently that if the crisis in Iraq leads to the state’s failure, the Kurds have a right to self-determination. Days later, Ibrahim Kalın—adviser to Erdoğan and frequent designee to explain government positions in English—wrote an impassioned defense of a unified Iraq. It would be strange if the government initiated domestic legislative action in response to the Iraq crisis without first sorting out what exactly its unified position on the crisis was.

More likely, the bill on the Kurdish Issue solution is tied directly to the worst-kept secret in Turkey: Erdoğan’s upcoming presidential bid. During his tenure, Erdoğan has often made small but flashy gestures toward solving the Kurdish Issue during election season. The Prime Minister still commands a tricky coalition of forces. It includes urban Kurds, who want to see progress on a solution, and religious nationalists, who will bristle at concessions too swift or numerous.

Erdoğan plainly wants to win the presidency on a single ballot, and he needs both of these voter groups in support to do so. Hence, this bill. It signals to Kurdish supporters that he is serious, if deliberate, in his efforts to solve the long-running conflict. To conservative nationalists, it indicates that the Prime Minister will make no immediate sweeping changes and will pair attention to security with any conflict de-escalation.

As much as Erdoğan benefits from cracking down on free media, weakening Turkey’s institutions, and concentrating power in his person, bills like this one are the primary reason Erdoğan continues to rule Turkey. No other Turkish politician has deciphered how to command such an effective—and impressively stable—coalition. The joint opposition’s management of Ekmeleddin Ihsanoğlu’s presidential campaign inspires precisely zero confidence that it is any closer than it has been over the last decade to offering a viable political alternative. Thus, we can expect more artful baby steps toward a solution to the Kurdish Issue in the coming years under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

This article was originally posted in Ottomans and Zionists.