The Return of the Tankers

On June 13, two oil tankers from Japan and Norway were attacked near the Strait of Hormuz, where nearly 30% of the world’s shipping passes through. Shortly after the crews abandoned their ship, the US, UK, and Saudi Arabia blamed the Iranians for the tanker assault. Iran stridently denied the accusation. Yet its leadership has routinely threatened that if they cannot export oil, no one else will. As the US seeks to cut all Iranian oil exports, Iran’s threat seems to have become a reality.

With the Iranian economy shrinking 6% this year after the US imposed its campaign of “maximum pressure,” Iran likely employs these tanker attacks as a means to respond forcefully without escalating the conflict into a full-fledged war. Knowing that many US and international politicians carefully monitor the security and stability of the international oil trade, Iran believes it can increase its leverage vis-à-vis the US by threatening this supply. Under this logic, enough Iranian attacks would induce the US to lift its crushing sanctions.

Western markets and leaders have responded to the threat of a tanker war with great anxiety. On the day of the attack, oil prices jumped 2%. US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said that the “unprovoked attacks present a clear threat to the international peace and security, a blatant assault on the freedom of navigation, and an unacceptable campaign of escalating tension by Iran.” According to the Washington Post, if “the strait is blocked or trade there is disrupted by conflict, analysts predict oil prices would surge.” This apprehension, however, seems misguided. The whole situation smacks of déjà vu.

China gets 91% of its Oil from the Straight, Japan 62%, & many other countries likewise. So why are we protecting the shipping lanes for other countries (many years) for zero compensation. All of these countries should be protecting their own ships on what has always been….

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 24, 2019

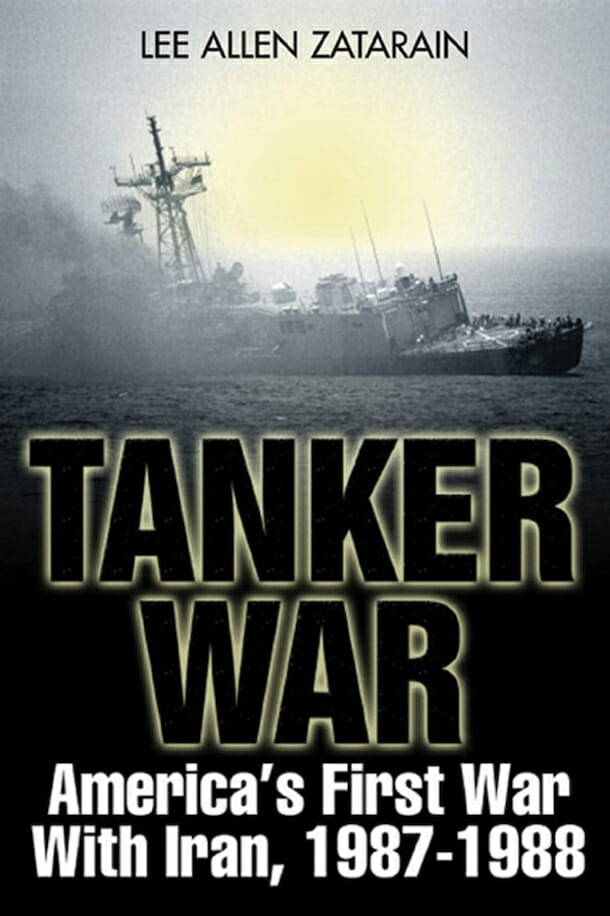

Less than forty years ago, during the Iran-Iraq War, Iran tried to disrupt the world’s crude oil supply by attacking tankers in the Gulf region. The “Tanker War,” as it was called, started in 1984, when Iraq attacked Iran’s oil terminal and tankers at Kharg Island. Iran then retaliated by hitting tankers from Arab states that carried Iraqi oil, thus fueling the Iraqi war effort.

When analyzing the current crisis, numerous pundits and historians use the 1980s attacks to rationalize the seriousness and threat of “Tanker War” 2.0. Similar to the 1980s, they argue, “the supply to the entire Western world could be at risk” since the “Tanker War led to a 25 percent drop in commercial shipping and a sharp rise in the price of crude oil.” These arguments omit the fact that oil prices skyrocketed during this period not because of tanker attacks but because oil production fell after the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran.

More importantly, these commentators overlook the actual impact of these attacks. The Iranian assaults did not close the Strait of Hormuz; it only affected two percent of shipping in the Gulf, and it did not raise the price of oil. To offset any lost oil, other Gulf countries simply produced and exported more oil. As the Chicago Tribune wrote at the time, “Despite concentrated attacks in the Persian Gulf against tankers by Iraq and Iran, oil exports are continuing to flow normally out of the troubled waterway.” Even when the “Tanker War” reached the pinnacle of tensions and threats, the reaction by the rest of the world and the oil market was subdued.

Modern-day pundits assume that because the US intervened in 1987 by providing military protection to Kuwaiti ships in Operation Earnest Will, any attacks on tankers in the Gulf are serious and should be met with force. But it’s important to note that the US dragged its feet when deciding to protect Gulf tankers. In the book, Tanker Wars, Martin Navias and E.R. Hooton write that “[o]ne of the most outstanding political features of the Tanker War must surely be the fact that for six years the international community did little to halt the attacks on merchant shipping either by sending sufficient forces into the Gulf in order to protect neutral vessels physically or by bringing meaningful pressure on the parties to halt anti-shipping strikes.” The US finally decided to protect Gulf shipping and stop the tanker attacks in mid-1987 when the Kuwaitis asked the Soviets and the Americans to provide protection.

The Tribune article also reported that numerous Gulf-based diplomats believed the Reagan administration was “exaggerating the war threat,” at the time, “to justify their reflagging operation” in order to restore US “credibility among moderate Arab states and checking the growth of Soviet influence” in the region. Accounts from then-Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger confirm such thinking. Weinberger said the administration went ahead with the operation because “there were a lot of theories around the world that [the US] would never…put ourselves in danger” and because he did not want the “Soviet Union to get a foothold in the region.”

This issue goes to the heart of the disjuncture between the 1980s “Tanker War” and the recent attacks near the Strait of Hormuz. The US didn’t mobilize naval assets to protect shipping because of Iranian attacks, they did it to boost their own international standing and curb Soviet influence yet again.

How does this history lesson apply to today’s conflict? First, it proves that, even at its worse, attacks on Gulf tankers yields few negative ramifications for trade or energy security—tankers are hard to sink, and other oil-producing nations simply replace sunken supplies. It also suggests that the Reagan administration did not race to secure crude shipments in the Gulf when they were being attacked during the Iran-Iraq War. The US slowly embraced military action not because it felt compelled to protect oil shipments but because it did not want the Soviets to gain an advantage by protecting Gulf shipments. Therefore, the “Tanker War” was not as frightening as modern experts suggest. In the words of Robert Reid, an international correspondent for the Associated Press during the Iran-Iraq War, the current situation is “way cooler” than it was during the height of the “Tanker War.” This is because, in the 1980s, Iran was directly waging attacks on tankers to induce superpower involvement. Now, however, the Iranians must carefully decide which tankers to attack since they need European and Arab nations to join them in their confrontation with the US.

Recently, most commentators have criticized President Trump for calling the recent attacks “very minor.” While his unwise strategy provoked this new US-Iran confrontation, his assessment of the tanker conflict is largely accurate. History confirms that another tanker war will not be as menacing as experts think.

But the historical analogy also encourages caution from the US. When the US Navy began escorting tankers in the Persian Gulf in 1987, some of its ships were attacked and others came very close to hitting mines. If the US decided to launch another Operation Earnest Will to protect tankers, it would occupy a substantial number of the Fifth Fleet and could invite some serious harm. Going into 2020, that’s the last result Trump needs.