Books

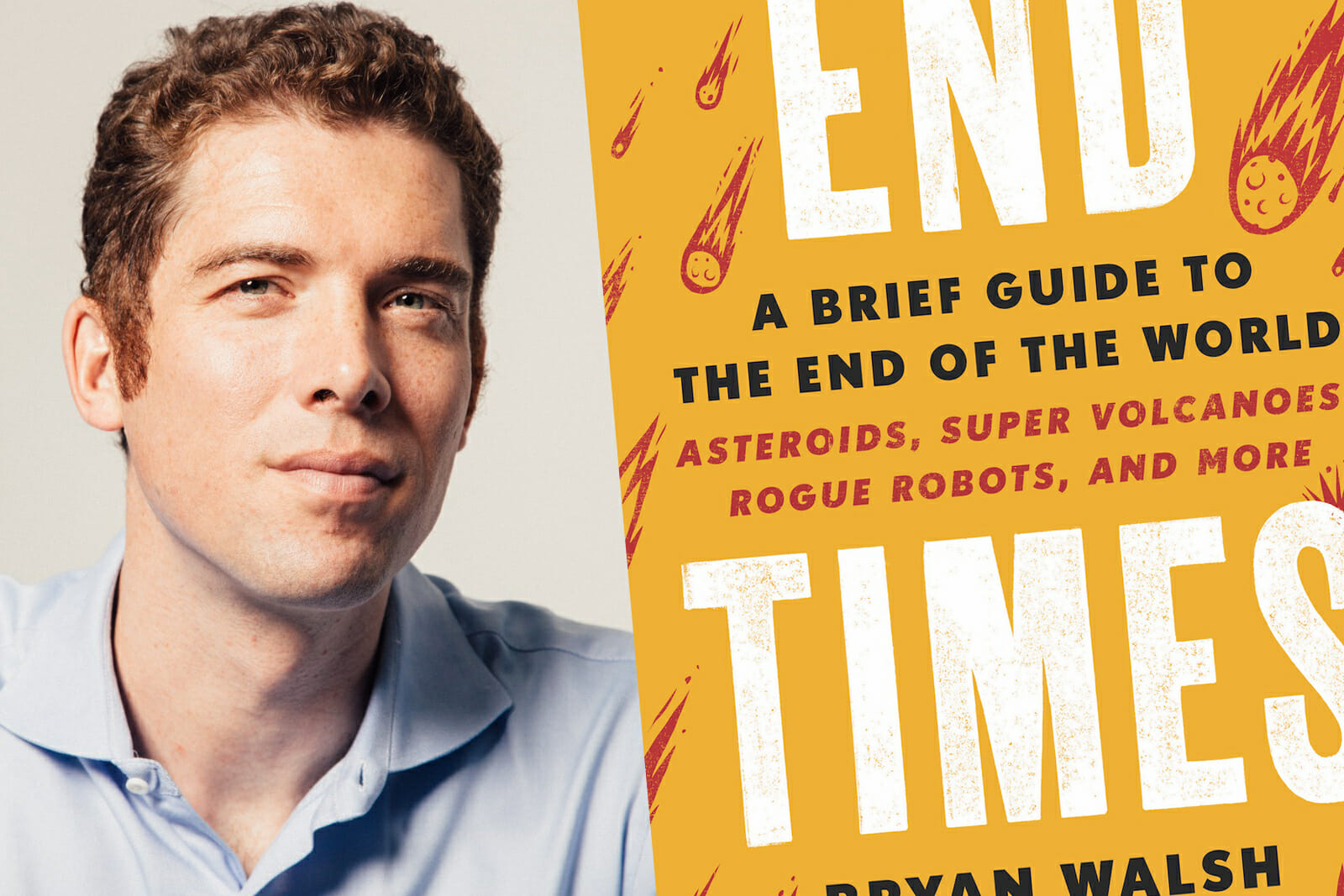

Q&A with ‘End Times’ Author Bryan Walsh

Some readers might brush your book off as being alarmist. What is your response?

I do my best to present the existential risks I cover in End Times in a responsible manner that puts them in proper perspective, making it clear that most of them are very, very unlikely to occur — especially in our lifetimes. But very unlikely is not the same thing as zero, even though we tend to conflate the two possibilities. I also try to make the case that it’s important to anticipate risks that will arise with new technologies like biotech and artificial intelligence because if we take steps to reduce that risk now, we’ll stand a much better chance of avoiding catastrophe in the future.

Why do Americans not take the end of the world seriously?

I’m not sure if Americans per se take the end of the world less seriously than other countries or cultures. A difficulty in imagining how very unlikely risks might take place is common to all cultures; in fact, I’d argue it’s inherent in human nature. But especially as our political culture has been frozen by polarization, we’ve completely lost the ability to anticipate and plan for the long term, and all of the risks I cover in End Times deal with the long term. If we can’t plan for the future, we can’t prepare ourselves for the possible end of the world.

Throughout history powerful societies have come and gone. There have been mass extinctions and one is happening now with countless animal and plant species dying off. Are we just buying time?

To some degree, yes! Human history is the story of the rise and fall of civilizations, and well over 99 percent of the species that have ever existed on this planet have gone extinct, one way or another. That fate is likely in our future — but the nature of that future is up for grabs. We could go extinct very soon, even this century, or we could continue to grow and expand for eons, even longer. Homo sapiens have only existed for a few hundred thousand years, but the average mammalian species exist for around a million years. We could far, far more in front of us, which means far, far more value — but only if we can remain alive.

Realistically, if an asteroid does careen towards Earth could humans persevere? The idea of Dr. Strangelove mines sound far fetched but the U.S. government has gamed out waiting out a nuclear war underground.

Asteroids actually represent one of the existential risks that we have the best ability to foresee and even actively prevent. We are currently tracking incoming near-Earth objects, and have found more than 90 percent of the potential NEOs larger than 1 km. And if we discover a new asteroid on a collision course, we have realistic plans for deflecting them, and sparing the Earth. But if a large — meaning bigger than a few miles across — asteroid were to impact the Earth, we’d be hard-pressed to survive, though underground vaults could protect a segment of the global population, which would, in turn, be able to eventually repopulate the planet.

What have been the reactions from people who plan for natural or manmade disasters?

People who plan for disasters understand the importance of planning. And planning for major existential risks involves many of the same steps we need to take to avert less severe but more common disasters, from smaller volcanic eruptions to disease outbreaks to low-level conflict. Anything that helps raise awareness that bad things can and do happen — and that we can plan in advance for them — is useful in their view.

Was there something in your career that led you to this topic for your book?

I reported on major disease events like SARS in Hong Kong and avian flu in Southeast Asia, and then I spent years covering climate change for TIME magazine. All of those experiences led me directly to looking at large-scale, long-term, global catastrophes — which in turn led me to write End Times.

The current U.S. administration isn’t taking climate change seriously, but can you go into how bureaucrats, strategists, and planners at State and the Pentagon who are?

The Pentagon has always taken climate change seriously because it sees the effect that climate change will have on bases abroad and because it is used to planning for the long term. It sees the way that climate change can destabilize countries aboard, which can, in turn, change the security threats facing the U.S. The State Department, however, simply has less sway than it once did, under both Republican and Democratic administrations, and while under Obama State participated in global climate diplomacy, that has completely disappeared under President Trump.

Do you feel the private sector is rising to the challenge when say countering climate change?

Not really. I don’t think any of us are rising to the challenge of climate change. I think it’s good that we’re seeing more investment in renewable energy and energy efficiency, but the reality is that we’re not remotely on track to reduce carbon emissions significantly enough to avert the high possibility of very dangerous climate change. We’re simply not.

The end of the world is often the subject of Hollywood movies. What do they typically get wrong? What’s is one you’ve particularly enjoyed?

Any Hollywood movie needs to cram in what would be a long and painful event into the course of a two-hour movie. So it’s usually that concision that introduces errors, as well as the need to create single characters who can save the world when in reality it would have to be a global effort. But there are some that have told the story well — particularly Steven Soderbergh’s 2011 film Contagion, which brilliantly showed how a pandemic could spread around the world and bring society to a halt.

Finally, what do you want readers to take away from your book?

I want readers to understand that existential risks are real, that the end of the world could happen, and it could be human beings who bring it about. At the same time, I want people to understand that we have the power to protect ourselves, that we can make a difference, that we are not doomed to end times and extinction. The power — either way — is in our own hands.