Politics

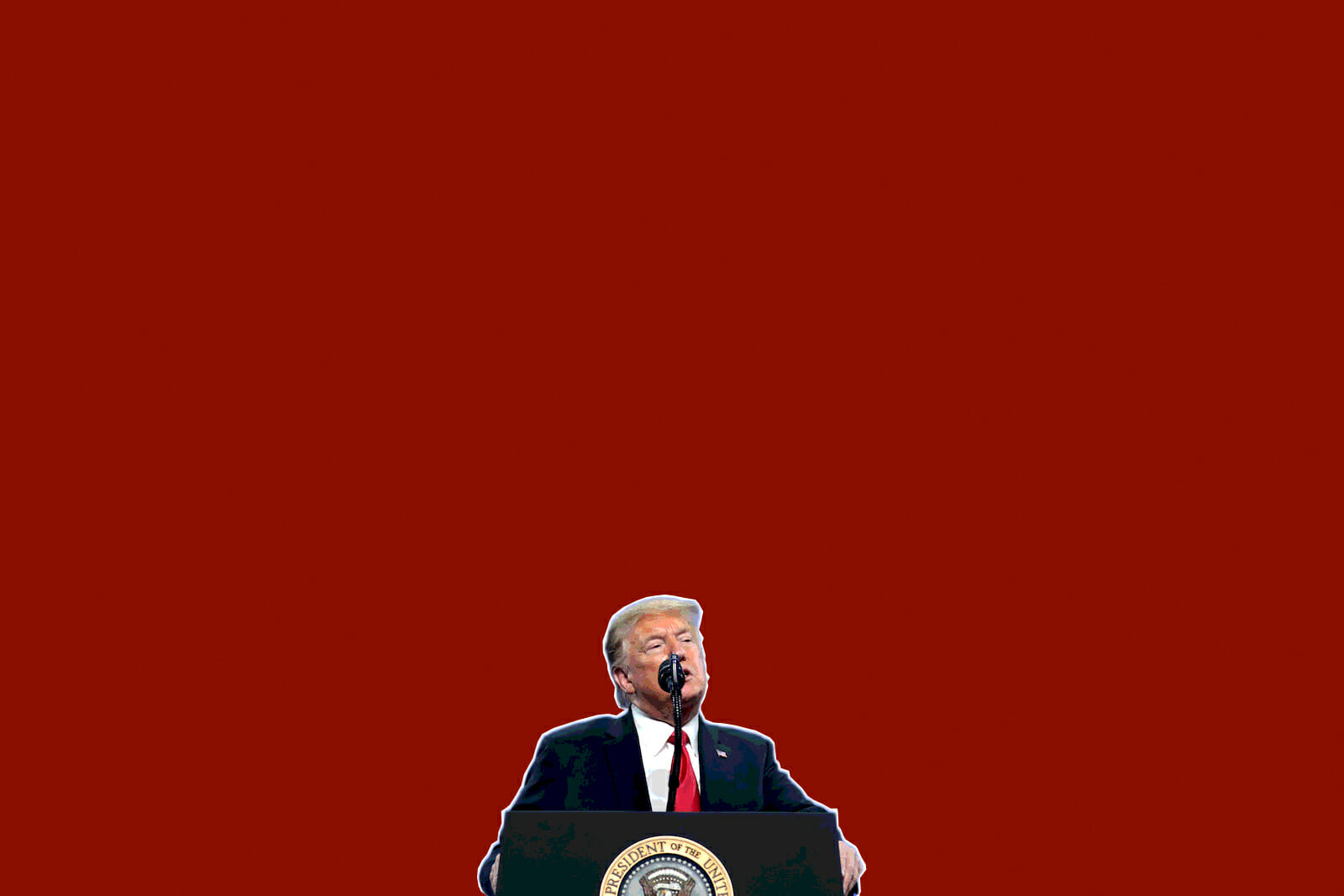

Burying the Hatchet Act: Donald Trump’s Unconventional Convention

Conventions suggest norms, a set of accepted rules. Behaviour is agreed upon in advance. In the case of US political conventions, there is much cant and gaudy ceremony. Certain transgressions are simply not contemplated. But the Trump administration is freighted with transgression, deviation, and, in some cases, a whole set of new norms born in defiant violation.

With that pattern in mind, why stop at the Republican National Convention? Ethics experts are aghast. Commentators are up in arms at the behaviour of Trump officials who have gone into full electioneering mode. The distinction between office and party campaigner has been not so much blurred as obliterated. President Donald J. Trump, in keeping with his own extravagant reading of his office, was not campaigning as a candidate but as the president with the office at his disposal. The White House, in short, had been mobilised in an official capacity to assist in his re-election. Trump appointees had been enlisted in the effort. “You’d be forgiven,” mused Rebecca Ballhaus of the Wall Street Journal, “for thinking the Republican National Convention was being hosted at the White House.”

This sparked interest in a piece of legislation that would otherwise remain part of the obscure, corroding statuary of the Republic’s laws. “The Hatch Act was the wall standing between the government’s might and candidates,” tweeted the former head of the US Office of Government Ethics, Walter Shaub. “Tonight a candidate tore down that wall and wielded power for his own campaign.”

The sum effect of the Hatch Act, which conditionally exempts the president and the vice president, is to prohibit federal employees from participating in partisan political activity in their “official authority or influence for the purpose of interfering with or affecting the result of an election.” Activities covered by this injunction include the official employment of the employee’s “official title while participating in political activity” while political activity is defined as “an activity directed towards the success or failure of a political party, candidate for partisan political office, or partisan political group.”

At the Republican National Convention, such injunctions had become baubles to be ignored. There was his pardon of Jon Ponder, convicted for bank robbery. There was Trump’s departure from convention in giving his acceptance speech at the South Lawn of the White House, a point that commentators tried to link to a legal breach. “It is legal,” Trump had foreshadowed with scorn. “There is no Hatch Act because it doesn’t pertain to the president.”

What mattered more were those employees the Hatch Act is supposedly designed to bar from such displays of partisanship. There was US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo spouting hope and praise from Jerusalem and campaigning on what was a taxpayer-funded foreign trip. A nice touch to the whole proceedings was that in doing so, Pompeo was effectively negating the very memo he had signed off on: that Senate-confirmed officials are barred from appearing at political party conventions or convention-related events.

In doing so, he certainly delivered a roguish cat amongst the pigeons. Former foreign policy adviser in the Obama administration Lauren Baer imaginatively concluded that this would somehow impair “the ability to conduct diplomacy free from politics.” (Where has Baer been?) Ilan Goldenberg of the Center for a New American Security was offended to “find the Secretary of State illegally deploying government resources, to use Jerusalem as a political prop to appeal to evangelicals.” A violation of protocol and law, but an act of mercenary political marketing.

Acting Homeland Security Secretary Chad Wolf, in presiding over the naturalization ceremony, was even more flagrantly in breach of the Hatch Act. The justification given to Ballhaus was that the White House “publicized the content of the event on a public website this afternoon and the campaign decided to use the publically available content for campaign purposes.”

Wolf’s presence was enough to see US House Representatives Raja Krishnamoorthi and Don Beyer dash off a note of concern to Henry J. Kerner of the US Office of Special Counsel. They requested an investigation, to be conducted by the Office of Special Counsel, on whether Wolf “and other senior members of the Trump administration violated the Hatch Act on August 25, 2020 through using their positions, official resources, and the White House itself, to participate in the Republican National Convention.”

Kerner claims to be a fan of the Hatch Act, taking issue with arguments that it is obsolete, “the federal election law equivalent of the stagecoach.” Its principles, he argued in February this year in the Federal News Network, “are as important today as when the law first passed.” He also warned Trump last year about violations of the Act by the president’s counselor Kellyanne Conway. “Ms. Conway has repeatedly violated the Hatch Act during her official media appearances by making statements directed at the success of your re-election campaign.” In recommending terminating her retainer, Kerner suggested that not punishing such breaches would “send a message to all federal employees that they need not abide by the Hatch Act’s restrictions.”

And so it came to pass. Conway poured scorn on the Act. “Let me know when the jail sentence starts.” The Trump administration, for its part, proceeded to quietly defang the Merits Systems Protection Board, the body responsible for policing the Hatchet Act and an agency of appeal for federal employees disciplined, demoted, or fired.

The Office of Special Counsel was not ignorant about the convention logistics but decided to distribute a mild note of “general advice” that did “not purport to address every situation that could result from holding a political event at the White House.” The opinion also chose to ignore the provisions of the Hatch Act covering the president in barring him from compelling employees “to engage in…any political activity including…working…on behalf of any candidate.”

This was too much for Shaub. “It happened on Henry Kerner’s watch,” he fumed. “With ample advance warning, he chose not to use the bully pulpit of his office…to object to this travesty or arm the people with detailed information about what was prohibited.” But even he was gloomily impressed by what he considered Kerner’s devilry in attempting to deal with this mess: “he’s a fast-working fixer.”

The Hatch Act was being made to wither with each speech, yet another relic, yet another instrument to succumb to Trumpist vanity. White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows, in airing his thoughts to Politico on the subject, was brutally frank. The Hatch Act was there for the burying. “Nobody outside of the Beltway really cares. They expect that Donald Trump is going to promote Republican values, and they would expect that Barack Obama, when he was in office, that he would do the same for Democrats.” There was much “hoopla” made about the convention only because it had “been so unbelievably successful.” To those who breach regulations, ethics and even the law, go the spoils.