After Four Years and 400 Policies, Advocates and Lawyers Question whether Biden can Save Asylum

As 2021 begins, many are looking ahead to President-elect Joe Biden to undo many of the controversial policies passed under the Trump administration, especially those on immigration. President-elect Biden stands in stark contrast to his predecessor, who ran in 2016 on an anti-immigration platform, decrying Mexicans as “rapists” who are “bringing drugs [and] bringing crime,” and pledging to build a “great, great wall on our southern border.” Biden has promised to restore policies similar to how they were pre-Trump when Biden was vice president in the Obama administration. Yet, advocates and lawyers working with asylum seekers say these policies—and their impacts—may not be so simple to reverse.

“I don’t know that it’s ever going to be the same again,” said Ann O’Brien, Director of community engagement at Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services (IRIS), about the refugee and asylum programs in the U.S. “I think there are probably some changes that they may not even be able to undo.”

Since President Trump took office in January 2017, the administration has enacted more than 400 executive actions on immigration. The most infamous of these policies include the ‘travel ban,’ better known as the Muslim ban, which enacts immigration restrictions on nationals from predominantly Muslim countries; the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), or the “Remain in Mexico” policy, which forces asylum seekers to wait in Mexico until their court dates; and the termination of DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) which freezes the pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants (“Dreamers”) who were brought to the U.S. as children.

Advocates working along the border attest to the drastic changes in policies over the past four years. One of these is Sister Norma Pimentel, who has worked with asylum seekers for over twelve years. Pimentel, the daughter of Mexican immigrants, works as the Director of Catholic Charities in Rio Grande Valley, Texas, just across the border from Matamoros, Mexico, where the infamous migrant tent-camp has bourgeoned. Recently named one of Time’s 100 Most Influential People for her work on the U.S.-Mexico border, Pimentel decries what she describes as President Trump’s most inhumane policy: the Migrant Protection Protocols.

“MPP is a horrible policy that has totally disregarded respect for human life [and] has no concern for humanity at all,” she said. “The only aim is to avoid seeing human suffering. MPP does that, it dehumanizes.”

President-elect Biden has said he will end the travel ban and MPP and reinstate protections for Dreamers in the DACA program during his first 100 days in office. This is part of his 100-day agenda, which reverses a number of the Trump administration’s restrictive immigration policies in an attempt to restore the refugee and asylum programs.

Advocates and lawyers alike, who have been fighting against the government’s policies for nearly four years now, doubt whether Biden and the U.S. will ever be able to fully eliminate the impact of the Trump-era immigration policies.

“[The Biden administration] definitely won’t be able to undo the ramifications of what’s happened,” said O’Brien. “I don’t think that the undocumented population and asylum seekers will ever trust the U.S. government like they did before these past four years. I don’t know that that can ever be repaired, that sense of trust in the U.S. as a beacon of hope and safety.”

Over the past four years, the Trump administration has dismantled the country’s 40-year-old asylum and refugee systems.

It began with the travel ban, better known as the ‘Muslim ban,’ which originally banned nationals from seven predominantly Muslim countries from entering the U.S. for 90 days (Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen), suspended entry of all Syrian refugees, and ended the entire Refugee Admissions Program for 120 days. After facing a slew of lawsuits, the administration tweaked the policy until it was upheld by the Supreme Court in a 5-4 decision. Most recently, in January 2020, President Trump added six countries to the list to face travel restrictions, all of which have considerable Muslim populations.

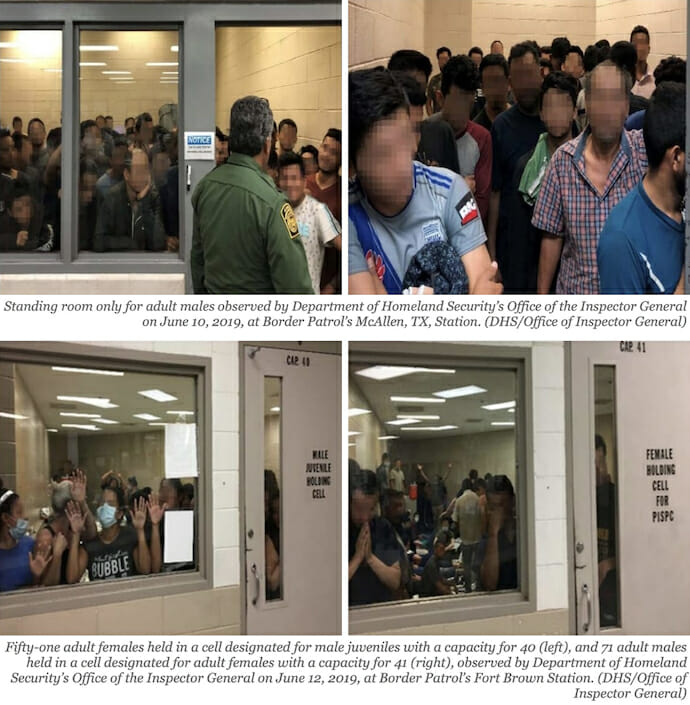

Next came the “zero tolerance” policy in April 2018, which criminally prosecutes all immigrants who cross the border and notoriously stripped children from their parents, sending them to wait indefinitely in derelict holding facilities. Nationwide outrage from Republicans and Democrats alike forced the administration to end the policy after just three months. During the policy’s short tenure, “up to 3,000 children may have been separated from their parents,” according to a Congressional Research Service report. Over a year later, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) found that the administration continued to separate families—over 900 parents and children. More than two years later, lawyers still cannot find the parents of hundreds of children who were separated.

Surges of migrants in 2018 and 2019 re-intensified a nationwide focus on asylum at the southern border. These so-called caravans, consisting mainly of families and unaccompanied children, brought hundreds of thousands of Central Americans through Mexico to the U.S. border.

Fleeing violence and extortion from gangs, these individuals sought refuge in the U.S. from their home countries of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras—countries with some of the highest homicide rates in the world. At the time, President Trump characterized the asylum seekers as “criminals” leading an “assault on our country.”

Doubts about how Mexico can provide a safe place for asylum seekers to wait for their court hearings have infuriated asylum advocates. “Dumping [asylum seekers] in Mexico, which has its own problems, and is not equipped” is not a solution that Andrea Leiner, Strategic Plan Coordinator of Global Response Management (GRM), sees as viable. Leiner worked with GRM as they mobilized to the migrant camp in Matamoros, Mexico to protect migrants during the coronavirus outbreak. “If we [the U.S.] weren’t equipped to handle this, how is Mexico equipped to handle an influx of hundreds of thousands of people who need services and help navigating the system?”

Outrage over the expulsions of asylum seekers to dangerous locations continued in the summer after MPP was implemented when President Trump signed Asylum Cooperative Agreements with Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. These agreements are modeled after what is called a “Safe Third Country Agreement,” in which asylum seekers are returned back to one of these three countries if they pass through it before arriving in the U.S. and are told to seek asylum there. This policy is based on the idea that both countries who sign onto the agreement are “safe” for asylum seekers—a condition which advocates and lawyers say is not the case in any of these three countries.

Taylor Levy, an immigration attorney in El Paso who works to provide free legal representation to asylum seekers, described the situations her clients have fled from in Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador as anything but safe. “The people I’m working with are fleeing cartel violence,” she said. “And in Central America, the cartels and government are basically one and the same. We work with a lot of people who have family members murdered, a lot of domestic violence cases, and cases where the abuser is involved with the gangs.”

The onslaught of policies from the Trump administration has stifled the hopes of many asylum seekers. “It’s a process that’s seemingly intended to break down the human spirit, so they say, ‘I give up,’” said Michelle Mendez, who works with the Catholic Legal Immigration Network to provide legal services to asylum seekers. “And maybe they give up and they go back home where they get murdered. Maybe they give up and they try to enter illegally because they figure ‘I might as well try, but I can’t sit here in these terrible conditions as I await my court hearing.’ And then if they do that, they are going to [face] really tough consequences under federal law.”

These federal policies, which severely restrict immigration have left not only asylum seekers but also advocates and lawyers distraught and overwhelmed. “They’ve just said, ‘Okay, we want to completely dismantle the system. We’re going to do death by a thousand cuts and push through as much as we can as quickly as we can and really overburden the courts,’” said Brian Griffey, North America Researcher for Amnesty International, about the Trump administration. “All the lawyers across the country working on immigration law are completely overwhelmed, burnt out, or traumatized themselves and working with traumatized communities who have been subjected to horrible treatment. It’s been such a travesty of justice.”

The Trump administration has faced hundreds of lawsuits against its policies, especially those on immigration. The ACLU alone has filed nearly 400 lawsuits and other legal actions against the administration since 2017—far outpacing the number of actions filed against President Obama during his eight years in office.

“Trump’s policies are incomparable [to those under prior administrations],” said Katrina Burgess, Associate Professor of Political Economy at the Tufts University Fletcher School, in regard to the degree of escalation in immigration policies after the 2016 election. “It’s like the previous policies on steroids.”

Many trends from prior administrations have been exacerbated during the Trump administration. Notably, the number of arrests and deportations of undocumented immigrants in the United States were actually higher under Obama than Trump until 2019. However, the number of arrests has increased nearly every year since Trump took office, while they decreased almost every year of Obama’s administration. The number of deportations during the Trump administration is also far below the numbers during Obama. Yet, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the organization in charge of deportations, cited that this is largely due to “a growing immigration court case backlog,” as well as “judicial and legislative constraints,” which contributed to challenges in enforcing deportation orders.

Indeed, one of the most prominent trends during the Trump administration is the soaring backlog and rising denial rates of asylum cases in immigration courts.

Before the coronavirus pandemic outbreak spread across the world, the backlog of cases waiting to be heard by U.S. immigration courts surpassed 1 million, a number which nearly doubles the backlog from Obama’s final year in office. Since the pandemic, in which courts have been entirely halted, the backlog has increased by hundreds of thousands. In 2019, asylum seekers waited an average of 696 days for their cases to be heard. This number is now up to 811 days, and continuing to increase. Many locations have an average of 1,450 days—over four years.

Once their cases are finally heard, the chance of being granted asylum is becoming increasingly slim. The Trump administration has worked to plummet the rate of asylum approvals nationwide. The denial rate has increased to a record high of 71.6% under President Trump, up from 54.6% during President Obama’s final year in office. But this denial rate is not constant across the U.S.—it varies significantly depending on the location of the court and the particular judge.

“There is an arbitrary denial of justice to migrants and asylum seekers depending on where they’re applying for protection or having their cases heard,” said Griffey. “If you cross the Texas border, or if you’re in Texas, you’re likely not going to get settled. Your chances are better out West, in California.”

Indeed, an asylum seeker is over 60% more likely to be approved if their case is heard by a judge in San Francisco than if their case is heard by a judge in El Paso.

Those unlucky enough to be rejected by a Texas court or otherwise denied asylum are sent back to their home countries with no protections from the threats that forced them to migrate in the first place. “It’s so terrible to see a mother returning from her asylum hearing crying, devastated because the officer who took her case told her, ‘Sorry, you don’t have a case. We are rejecting your asylum,’” said Pimentel, who frequently interacts with families before and after their court hearings. “[The mother] says, ‘But my husband was killed and…I can’t go back because I will be killed, and my child will be in danger.’ And [the asylum officers] say, ‘That’s not our problem, that’s your problem,’ and they send her back.”

The Trump administration has defended their policies as adhering to a basic “commitment to public safety, national security, and the rule of law,” as stated by then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions when the zero-tolerance policy was announced. The administration has also framed them as a humanitarian defense—as an “unprecedented action that will help address the urgent humanitarian and security crisis at the southern border,” said then-Secretary of Homeland Security, Kristjen Nielsen about MPP.

Advocates like Pimentel don’t see the policies in the same light. “There are issues we must address as a nation and one of them definitely is to protect and safeguard who enters our country,” she said. “But at the same time, we must not lump together and treat everybody as a criminal just simply because they are entering our country. Asking for asylum does not make them a bad person. I think we’re treating the whole issue of immigration unfairly, especially for those families who are seeking protection and safety.”

The administration’s policies toward individuals seeking protection have only become more restrictive since the onset of the pandemic. On March 20, 2020, under the guise of a public health concern, the Trump administration enacted U.S. Code Title 42. This law, created in 1944, allows the government to suspend entry to the U.S. of all foreign nationals who it deems a danger to introducing a communicable disease into the country.

Top scientists from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) initially refused to comply with the order, saying that there was no evidence that enacting Title 42 would slow the spread of coronavirus. Eventually, the administration “forced” them to enact the policy, as reported by the Associated Press.

“COVID-19 erupted everywhere, and the Trump administration’s response was to put in place a border-wide ban on reception of all asylum seekers,” said Griffey. “This is something that Stephen Miller had been seeking to claim for years, which is that, in the most racist way you can try to frame it, migrants are vectors for disease which is why they should be excluded from accessing asylum procedures and instead summarily deported back to their countries of origin.”

Stephen Miller, senior advisor to President Trump and the architect of the Trump administration’s anti-immigration policies, once said that he “would be happy if not a single refugee foot ever again touched American soil.” Former White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders claimed that such a statement is “certainly not the policy of the administration.” Yet, this is exactly what Title 42 has done.

In just two weeks after enacting this statute, the U.S. deported over 7,000 migrants and 400 unaccompanied minors without asylum processing. In the eight months since this policy was enacted, over 250,000 people have been deported.

Not only have asylum seekers been unable to file new cases, but asylum seekers with cases pending have had their processes frozen. In March, the Trump administration also halted immigration court proceedings amidst the pandemic. The Department of Justice and Department of Homeland Security announced in July that they would restart MPP hearings once California, Arizona, and Texas progressed to Stage 3 of their reopening plans, the Department of State and Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lowered their global health advisories to level 2, and when the Mexican government categorized Mexican border states as “yellow.”

As coronavirus cases surge to record highs across the United States, and with no action from the Trump administration to contain the spread of the virus, these requirements are far from being attained.

“It’s just an uphill climb for people to try to navigate the system,” said Leiner. “It’s led to quite a hopeless feeling [for asylum seekers]. Nobody is in control of their own destiny right now.”

Migrants and advocates have begun to hope that the new presidential administration in January will reverse these restrictions and give migrants back some control over their futures. After President-elect Biden was announced the winner of the 2020 presidential election, asylum seekers waiting in Mexico under MPP celebrated, believing that the Biden administration would finally allow them to pursue their asylum claims, and permit them to stay in the U.S. while they wait.

Because most of the Trump administration’s immigration policies were made via executive action or regulatory changes, they can quickly be reversed on paper.

But Leiner warns that it won’t be that simple. “It’s incredibly difficult with the change in the election,” she said. “We have noticed that there is some hope in [the migrant] camp that perhaps things will be different. Even if [MPP] is ended, implementing another strategy means we’re still looking at least another year of having large groups of people in Mexico who are kind of in this purgatory and processing them all and coming up with a meaningful solution. It’s going to be time and labor-intensive.”

How Biden manages these large quantities of migrants waiting along the southern border and how he responds to recent surges of migrants will be formative to his presidency. The actual implementation of reversing many of the Trump administration’s policies will prove to be much more difficult than just a signature on paper. “The logistics of this are overwhelming,” said Burgess. “Sixty-six thousand people have been sent back to wait [in Mexico]. Some of them, we have no idea what percentage, have given up and gone home. But multiple thousands are still waiting. So, if the Biden administration says MPP is off the books, what happens the next day? How is our infrastructure going to manage the sudden volumes of people requesting asylum, needing to be housed somewhere while they wait?”

Not only will there be challenges due to the asylum infrastructure, but the U.S. is still struggling with the outbreak of the coronavirus, experiencing its worst days of the pandemic yet. The number of cases and deaths only continues to rise, and hospitals are reaching their capacities.

“The Trump administration was incredibly effective at their war on immigrants. They created a perfect storm for torturing asylum seekers,” said Levy. “I think that we’re going to have to see creative solutions that involve justice and allow asylum seekers to have their chance to seek asylum but that also keep asylum seekers safe.”

Beyond the logistical complications, one of the most serious challenges facing the Biden administration will be uniting a sharply divided American electorate—a division which has largely been fueled by immigration.

“It’s a life issue, it should not be political,” said Pimentel. “But, unfortunately, it is very convenient to use [immigration] as a campaign strategy and it has become so political. People take sides.”

Although it was mainly overshadowed by the pandemic and economy in the 2020 election, immigration policy still played a significant role in the candidates’ platforms. Fearmongering about a “nationwide catch and release” policy under a Biden presidency was pushed by Stephen Miller, who simultaneously released a second-term immigration agenda for President Trump that included ideas such as elongating the freeze on new green cards and visas, expanding the travel ban, slashing refugee admissions to zero, and eliminating birthright citizenship.

This division and these extreme policies have left advocates stunned. “The fact that we allow things like this—issues that are critical to humanity—to be used as political, is so wrong,” said Pimentel. “Immigration and what has happened [along the border] is not blue or red. It’s a human reality and we must look at how to address it as one nation.”

The rhetoric that began during President Trump’s campaign has contributed to this party-line division. By characterizing asylum seekers as “some of the roughest people you’ve ever seen” and mocking their claims of fear for their safety, President Trump propagated false ideas about who asylum seekers are. He also fabricated the notion that asylum seekers are avoiding the law by claiming asylum, not abiding by it. Not only this, but he has criticized the asylum system in its totality, stating that “the asylum program is a scam” and falsely claiming that “the system is full, [the U.S.] can’t take you anymore.”

Michelle Mendez works as the Director of the Defending Vulnerable Populations Program at the Catholic Legal Immigration Network, a program that was launched in direct response to the “growing anti-immigrant sentiment and policy measures that hurt immigrants.”

Mendez described this idea of asylum being an illegal or sub-legal process as one of the biggest misconceptions about asylum seekers. “There’s nothing wrong with coming to the border the way asylum seekers do,” she said. “They present themselves at the border or come in surreptitiously and ask for asylum once they’re here. There’s nothing wrong with that. Those are the ways that you seek asylum. The person has to be on U.S. soil to seek asylum.”

Misunderstandings about the asylum process and asylum seekers help sow the deep political divides. Levy described how her work with her clients epitomizes this discrepancy between popular conceptions of asylum seekers and reality. “I work on so many cases with fourteen-year-old girls who were kidnapped by the gangs and raped and were going to be sex slaves for the cartels, and then they were rescued,” she said. “When you bring up the actual individual stories to people, they understand. They think ‘Oh my gosh, of course these people would want asylum!’ I think the misperception is that people think that it’s a bunch of liars. But that’s not the people I work with. The people who I work with are real asylum seekers with horrific cases who are losing their cases. And it’s not because they don’t deserve it, it’s because the way asylum works is way too narrow.”

A common belief is that asylum seekers are motivated by purely economic means. Although this is a valid case, other factors such as violence and destruction from natural disasters often drive Central Americans to emigrate. The economic narrative largely evolved from the historical trend of single individuals from Mexico migrating to the U.S. for employment. However, over the past ten years, the proportion of single individuals crossing the border has plummeted, as family units and unaccompanied minors have come to make up the majority of crossers.

“They’re not coming to America for a better job,” said Leiner. “This isn’t a migrant population, this is an asylum-seeking population who are fleeing organized crime, government persecution, violence, and just a horrible, horrible situation at home.”

While the U.S. continues to debate, those whose lives are affected by the policies are facing significant repercussions. “The damage is not going to be reversed,” said Burgess. “A lot of damage has been done to human beings, to people’s lives, [and] to families that cannot be undone. There’s no doubt that these people have been traumatized and trauma has a long-lasting impact.”

Yet, as the Trump administration’s reign comes to a close, the political divisions have only grown deeper. President Trump finally conceded the election but with only 13 days until Biden’s inauguration. His concession came a day after pro-Trump rioters stormed the U.S. Capitol in response to a speech by President Trump in which he continued to falsely claim that massive voter fraud stole the election for President-elect Biden and incited the riot. In the meantime, Central America has been struck by the year’s two most powerful Atlantic hurricanes within a two-week period, affecting more than 4.5 million people in the region. Shortly thereafter, U.S. Customs and Border Protection apprehended almost 1,000 unaccompanied children at the border in less than a week. Meanwhile, the Trump administration has fast-tracked border wall construction, in an attempt to finish it before leaving office, and continues to deport migrants under Title 42, while the virus rages domestically.

Although a solution may not appear immediately during the Biden administration, steps will be made to re-establish the asylum program. “Refusing to address the problem and putting up a barrier, that’s not an answer,” said Pimentel. “We need to respectfully respond to it and [under the Biden administration] I am confident there will be very good changes.”

In a time where the world is distanced both politically and physically, Pimentel urged Americans to try to connect to asylum seekers on a human level. “One of the first things I always ask [asylum seekers] is ‘¿Cómo estás?’ ‘How are you?’ It’s a moment of acknowledging their presence in front of me and to recognize that I see you and I am concerned for you—I see the suffering,” said Pimentel. “They chose to leave their country and journey north with hopes of entering a country where they believe they will be safe. And I’ve heard story after story of atrocities they’ve experienced along the way, people taking advantage of them and hurting them in many ways unimaginable. They’ve suffered a lot, mostly because they’re easy targets to take advantage of. And they enter our country and they’re just seen as a number or a problem. That’s who I see every day. Somebody who is desperately needing to be acknowledged, to be recognized, to be seen as a human being.”