Destroying Chilean Democracy: Australia’s Covert Role Five Decades On

The tear-squeeze remembering of those who died in the September 11, 2001 attacks on New York and Washington has become an annual event. In the words of U.S. President George W. Bush, it was an attack on “our very freedom.” The U.S. had been targeted because it was “the brightest beacon for freedom and opportunity in the world.”

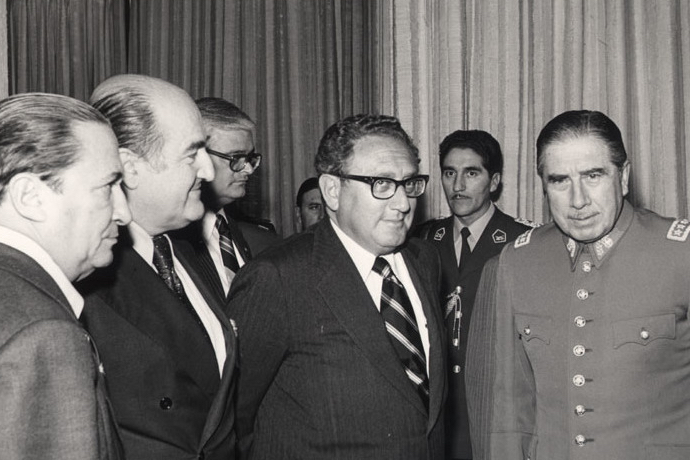

Five decades ago, that brightest beacon of freedom and opportunity proved instrumental in destroying a democracy in Latin America. The 1973 coup that overthrew the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende in favour of General Augusto Pinochet, an anti-communist, pro-Washington butcher, received abundant logistical, disruptive support from the Central Intelligence Agency.

The election of the socialist Allende had caused rippling apoplexy in the White House, with National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger warning U.S. President Richard Nixon that something needed to be done about the Allende government, given its “insidious model effect.” In ultimately destroying this model of left-democratic insidiousness, they had help from a strange quarter.

In 1983, Australia’s Attorney-General Senator Gareth Evans told the Senate that no Australian security agency had gotten its hands dirty in activities that eventually led to the overthrow of Chilean President Salvador Allende. In what can only count as a stunning whopper of a statement, Evans stated the following: “To the extent that some intelligence cooperation activity may have occurred at an earlier time, there is no foundation for any suggestion that Australia in any way assisted any other country in any alleged operations or activity directed against the Allende regime.”

This pricked the ears of Clyde Cameron, a former Minister for Labor and Immigration in the Whitlam government. Cameron had previously told the ABC Four Corners program that Australian agents had been involved. His views, also conveyed in a letter, did nothing to “change the substance of the answer” Evans had given.

The letter from Cameron revealed his astonishment on becoming Minister for Immigration in 1974 that the department had been providing generous overseas cover for 19 full-time Australian Security and Intelligence Organisation agents. “I was further advised,” wrote Cameron, “that one of these so-called migration officers had been operating in and out of Santiago around the time of the military coup which murdered the democratically elected president of Chile.” Two points of interest are then disclosed: Prime Minister Gough Whitlam informed Cameron that he was aware of ASIS involvement; and that Cameron, off his own bat, found that his “ASIO ‘migration’ officer, together with ASIS, had acted as liaison officers with the CIA which masterminded that coup.”

The denial by Evans is also stranger given the 1977 admission by then opposition leader Whitlam to the federal parliament “that when my government took office Australian intelligence personnel were still working as proxies and nominees of the CIA in destabilising the government of Chile.” His comments came in the context of leaks from the first 8-volume secret report, authored by Justice Robert Hope as part of the Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security surveying the conduct of Australian intelligence activities. To this day, the detail on Australia’s Chilean operations in the report remains classified.

In February 1984, a Conference on Commissions, Contempt and Civil Liberties held at the Australian National University was told that Canberra had sent three intelligence officers to assist the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency in the aftermath of Allende’s coming to power. It was also an occasion for journalist Marian Wilkinson to discuss the leaks from the second Hope report. What it revealed was Canberra’s appetite for continuing a covert operations program encouraging international subversion without any coherent definition of that vague coupling of words “the national interest.”

As Wilkinson discussed, six Canberra mandarins had met in 1977 to endorse a program of covert action involving “‘dirty tricks’ in foreign countries, disruption, deception, destabilisation and the supply of arms.” (Rules-based orders are fine till they are inconvenient.)

Those in attendance at the meeting were the head of the Prime Minister’s Department, Sir Alan Carmody, Sir Arthur Tange of Defence, Sir Nicholas Parkinson of Foreign Affairs, Sir Clarrie Harders of the Attorney-General’s department, John Taylor of the Public Service Board and Ian Kennison, director of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service. The latter was keen to impress upon his colleagues that, were the covert program to be uncovered, it would be justifiably covered up and denied.

The subtext of the meeting was that Australia would happily continue the practice of supplying its own agents to the cause of its allies, notably the United States. Australia’s national interest only mattered in the service of another power.

In 2017, Clinton Fernandes of the University of New South Wales, along with barrister Ian Latham and solicitor Hugh Macken, girded their loins in an effort to access ASIS records on the Santiago station from the early 1970s. In their storming of the citadel of stubborn secrecy, documents began surfacing, released with teeth-gnashing reluctance.

In September 2021, the National Security Archive, that estimable source hosted by George Washington University, published a selection of Fernandes’s findings. They chart the evolution of the Santiago “station” that was requested by the CIA in the fall of 1970. Then Liberal Party external affairs minister William McMahon granted approval to ASIS in December 1970 to open the station at the heart of Chilean power.

In June 1971, a highly placed Australian official, whose name is redacted, began having second thoughts about, “The need to go ahead with the Santiago project at all, at this stage.” The “situation in Chile has not deteriorated to the extent that was feared, when we made our submission.” ASIS officials, despite begrudgingly admitting that “Allende had so far been more moderate than expected,” still wished the opening of the station to “go forward now, and not be deferred.” The pull of the CIA was proving all too mesmeric.

Once it got off the ground, the station endured various difficulties. A report from its staff in December 1972 notes concerns about the timeliness of reporting, the problems of using telegraphed reports, and how best to get communications to the “main office” securely. There is even a reference, with no elaboration, to “two most recent incidents” regarding “biographic details concerning” individuals (redacted from the document), something that did “little for our Service reputation.”

With the coming to power of Labor’s Gough Whitlam, a change of heart was felt in Canberra. In April 1973, the new prime minister rejected a proposal by ASIS to continue its clandestine outfit, feeling, as he told ASIS chief William T. Robertson, “uneasy about the M09 operation in Chile.” But in closing down the Santiago station, he did not, according to a telegram from Robertson to station officers sent that month, wish to give the CIA the impression that this was “an unfriendly gesture towards the U.S. in general or towards the CIA in particular.”

Five decades on, some Australian politicians, having woken up from their slumber of ignorance, are calling for acknowledgment of Canberra’s role in the destruction of a democracy that led to the death and torture of tens of thousands by the Pinochet regime. The Greens spokesperson for Foreign Affairs and Peace, Senator Jordon Steele-John, stated his party’s position: “50 years on we know Australia was involved, as it worked to support the U.S. national interest. To this day, Australia’s secretive and unaccountable national security apparatus has blocked the release of information and has denied closure for thousands of Chilean-Australians.”

In calling for an apology to the Chilean people, the Greens are also demanding the declassification of any relevant ASIS and ASIO documents that would show support for Pinochet, including implementing “oversight and reform to our intelligence agencies to ensure that this can never happen again.” With the monster of AUKUS enveloping Australia’s national security, the good Senator should not hold his breath.