China’s Rotational Ruler Model

The only system that can be described as similar to the Chinese “once-in-a-decade transition of power” practice in the 21st century is Plato’s rotational ruler model proposed in The Republic.

“Those who have come through all our practical and intellectual tests with distinction must be brought to their final trial…and when their turn comes they will, in rotation…do their duty as Rulers…when they have brought up successors like themselves to take their place as Guardians, they will depart…” A comparison shows that three common features and two pragmatic variations can be found between the Chinese system and Plato’s ideal. And this system, if well institutionalized, can achieve an advantage that democracy can produce—regular and peaceful handover of authority.

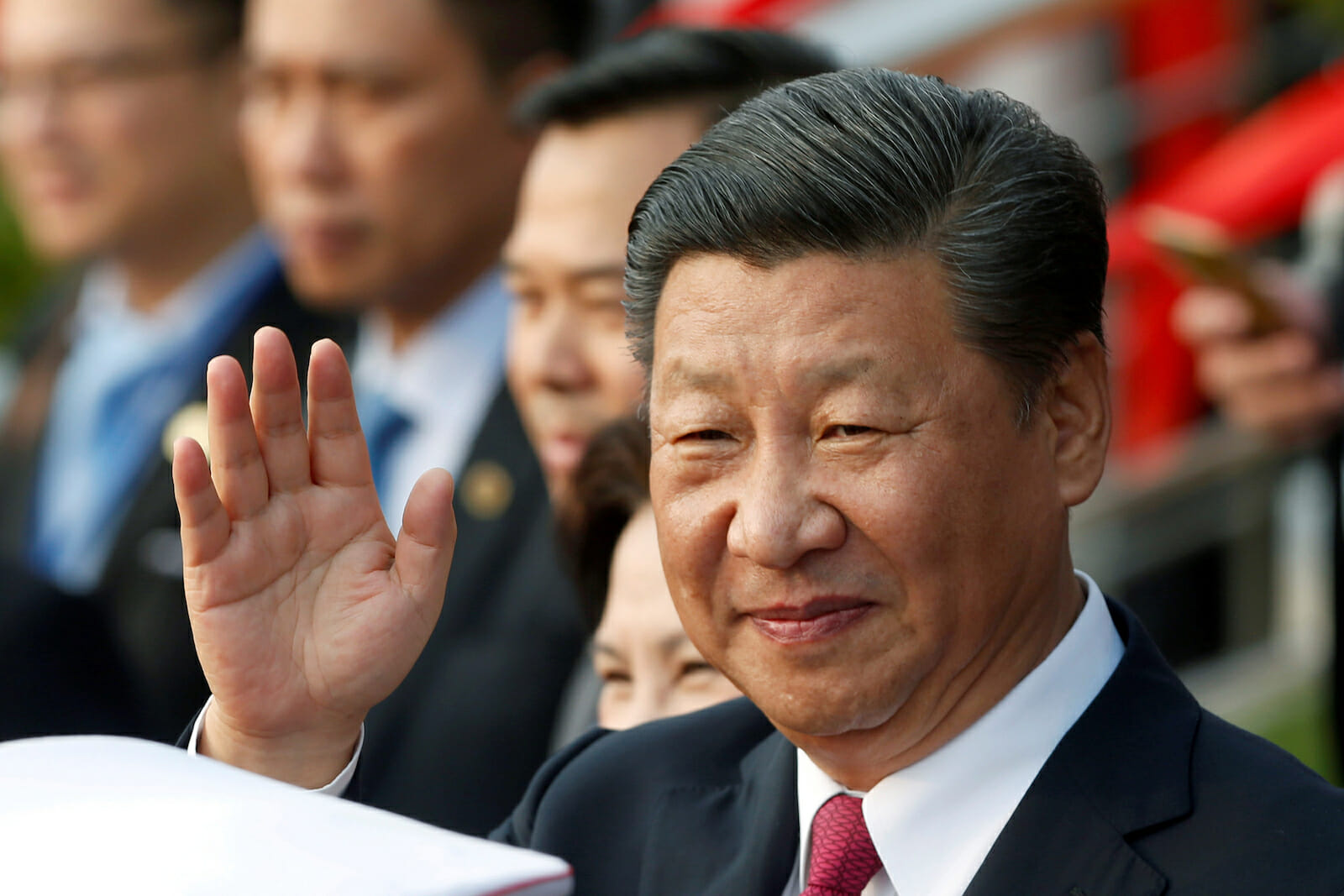

Before coming to power, Hu Jintao, Xi Jinping, and many other Politburo members had gone through certain types of party school training programs and been posted in rotation among several local administrative and/or functional ministerial positions as a sort of on-the-job training. Although the Chinese curriculum is not exactly the same as Plato’s mathematics (10 years), dialectic (5 years) and the post-dialectic “military or other office” apprenticeship (15 years), the fundamental principle is the same, namely, that only purposively trained for statecraft people can become rulers of the state.

The second common feature is that the rulers lead the state “in rotation” which in modern terms means “tenure.” In China, as imposed by Deng Xiaoping and subsequently stipulated in the constitution and certain administrative directives, there is a maximum limit of ten years (two terms of five years each) for an officer to hold a particular position. It has been a national anticipation that when the tenure comes to the end, the rulers in Beijing have to step down and retire. Hu Jintao’s complete retirement from both the state presidency and chairmanship of the party’s Central Military Commission in 2012 indicates that the practice has been institutionalized.

One of the main duties of the rulers is to bring up, assess and select their successors. Here is the third common feature between the Chinese system and Plato’s ideal. The selection of rulers is in no doubt arbitrary but there have been some signs of institutionalization in place. Firstly, it is supposed to be on merit. It has been generally expected that the selected rulers should have a good track record in heading at least two provincial governments. Secondly, age is a strict requirement for consideration. Thirdly, like Plato’s “final trial,” the two leading candidates have to serve five years in the Politburo for final assessment before formal assumption of the top posts of state president and premier respectively. So far, authority has been handed over to the persons without kinship to their predecessors. It seems meritocracy is working.

The arrangement that potential rulers are openly recruited in China can be deemed as the first pragmatic variation from Plato’s ideal. While Plato proposes a caste system for his “Guardian herd,” Chinese Communist Party membership is open to all citizens. It provides socio-political upward mobility opportunity to the general public, which is in line with the functional purpose of the two thousand years long Chinese tradition of civil service examination system. The satisfaction of the national aspiration for socio-political mobility through open and fair competition is a key factor for social stability and even legitimacy.

Nevertheless, the second pragmatic variation from the Platonic model that the Chinese rulers are allowed to hold private property and have a family has become the source of rampant corruption. Plato, who understood the weakness of human greed, explicitly prohibited his ideal rulers from having private property and family. Unfortunately, it is impractical and unrealistic. Therefore, it will be a great challenge for Xi Jinping to strike a balance between private property ownership and the declaration of his assets so as to put corruption under control.

The present political succession system in China can be viewed as a pragmatic and experimental implementation of Plato’s ideal in a large scale that it has been institutionalized as a huge human resources management system for public administration, political training as well as a selection of helmsmen as rulers.

This ‘Helmsman Ruler System’ has been initiated and is working smoothly. If this non-democratic Platonic political succession system can take root in Beijing, a politically stable and economically prosperous China will be able to resist the Western-centric policy of democratic global order for a ‘depoliticalized’ universe, and simultaneously construct a “pluriverse” in partnership with other emerging powers, thus bringing back multi-bloc geopolitics to the world.

From China’s close ties with the fellow members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, to Xi Jinping’s visits to Moscow, Africa and participation in the BRICS summit in Durban in March 2013 as his first diplomatic strike, it is discernible that the Chinese helmsman rulers have been making a series of “political” moves to identify friends and enemies (according to Carl Schmitt, the concept of political means a distinction of friend and enemy; Plato explicitly requests that the state rulers should have the ability, like a watch-dog, to distinguish “friend and foe”). These moves to construct a pluriverse are tactically going against the tides of depoliticization and neutralization for a liberal and democratic universe.

With a pragmatic Platonic ruler succession system, a non-democratic China has the potential capability to remold the global order and challenge the dominance of democracy as a ruler selection system. While many academics and analysts still focus on democratization in China, the game has already changed. The 21st century may be a comeback time for Plato, the master of non-democratic political philosophy.