A Rwandan Invasion of the Congo Would be Disastrous

“We don’t ask anybody for permission to intervene. We simply move in and sort the problem out.” Rwandan President Paul Kagame’s words to parliament in February of this year in reference to the ongoing instability in Congo’s Kivu region aren’t an idle threat, nor can they be written off as sabre-rattling.

Since 1996, Rwanda has been a persistent antagonist in the affairs of the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), particularly within the long-running Kivu conflict, both through direct military invasion and support of proxy Congolese forces such as M23 rebels. The West must not only take Kagame at his word but commit to opposing continued Rwandan aggression against its neighbour.

It must be stated initially that Rwanda does have legitimate security concerns in the Kivu region. Although drastically reduced in size and power from their peak in the early 2000s, the Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda (FDLR), founded and led by senior participants in the 1994 Rwandan genocide, still maintain basecamps and military forces in the region. The Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), a cross-border Islamist insurgency, routinely massacres villagers in the DRC and stages terrorist attacks in Uganda.

This is all true, and rightly a strategic concern for Rwanda. However, a rerun of Rwanda’s typical military solutions in the region should be opposed by Western policymakers as it is both demonstrably counterproductive and creates long-term strategic problems for both Africa and the international community.

First, Rwandan military intervention has failed in stabilizing the Kivus for 26 years; the Kivus are no closer to stability than they were in 1996. There is no reason for anyone in Western policy circles to think that another Rwandan ground incursion or a more successful M23 insurgency will finally restore peace to the area.

On a tactical level, Kagame’s primary foe in the eastern Congo, the FDLR, has been neutralized as an existential threat for over a decade. There is a zero chance of the remaining génocidaires seizing Kigali or even staging any kind of significant military operation into Rwandan territory. They lack the basic numbers, weaponry, and support necessary to challenge the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF), arguably Africa’s most proficient and professional military force, on their home turf. Considering the FDLR have been strategically defeated and pushed back into the DRC, what does Congo, Africa, or the West stand to gain from another Rwandan military invasion of the eastern Congo? The remains of the FDLR are an internal security concern for the DRC, not Rwanda.

The argument that Rwandan security necessitates an invasion of the DRC should clearly be rejected by the West. It becomes clearer that intervention should be opposed for the simple fact alone that the DRC is critical to the global economy and multiple sensitive supply chains. Another Rwandan invasion, especially one along the lines of what happened in 1998-2003 during the Second Congo War in which Rwanda occupied large tracts of the DRC for years, or even continued support for M23 rebels would be disastrous for both Africa and the global economy.

Some estimates for the DRC’s mineral wealth go as high as $24 trillion. Mining diamonds and gold are major drivers of economic activity, but equally important are the 3T minerals (tantalum, tin, and tungsten) alongside other critical minerals like lithium, cobalt, and coltan. All these lesser-known minerals are critical for the global economy and the world’s drive to decarbonize via new energy systems. Increasing demand for electric lithium-ion batteries and electric vehicles in particular is straining existing global supply. Unfortunately for all concerned, some of the DRC’s principal reserves for these valuable minerals are right in the middle of the Kivu conflict.

It’s no secret that the trade in mineral resources has funded violence in the DRC for decades; this is a well-established problem. Rwanda itself has already benefitted. Despite having few producing mines or deposits, Rwanda exports over $400 million worth of minerals per year, the majority in gold and coltan. Virtually all this coltan is sourced illegally from the DRC and smuggled across the border.

Putting aside the question of how or why these rare minerals are extracted (or who financially benefits), it must be established that any Rwandan conventional military operation in the Kivus will cause a fundamental and severe rupture to mining activity with subsequent knock-on effects for global supply chains.

Putting aside the question of how or why these rare minerals are extracted (or who financially benefits), it must be established that any Rwandan conventional military operation in the Kivus will cause a fundamental and severe rupture to mining activity with subsequent knock-on effects for global supply chains.

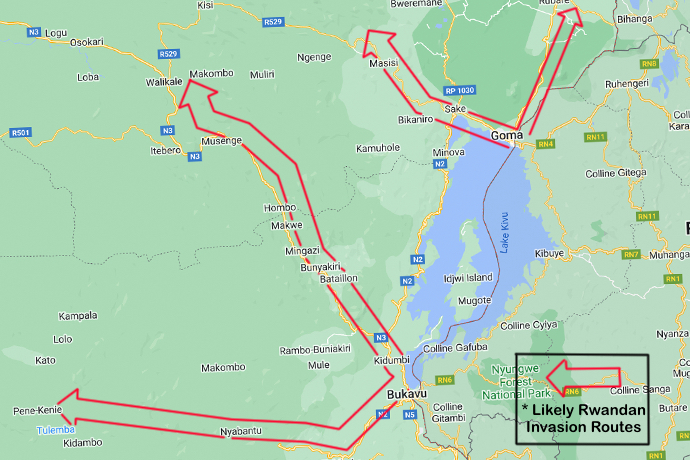

As can be seen in the map above, in the event of a Rwandan invasion of the eastern DRC, the main transportation routes and hub cities like Goma and Bukavu, that the regional mining trade depends on military objectives to be seized by the RDF or defended by the Congolese. Should this happen, they will not be in any condition for economic activity. The most likely routes for an invading RDF will take them through areas with a high concentration of mining activity. Even if the miners don’t flee the RDF, how will they get their wares to market through a battlefield, and who would be there to buy them regardless? The supply side of the DRC mining industry would be crippled, and after the dust settles, the eastern Congo minerals trade would be wholly in the control of Rwanda.

Finally, and perhaps of greatest concern to Western policymakers, a Rwandan invasion of the DRC would provide ample space for hostile non-state or proxy actors to intervene, as has been recently seen in places like the Central African Republic, Mali, Madagascar, Libya, or Mozambique. In all five examples, weak states imported the Russian paramilitary Wagner Group when domestic military forces were unable to exert control over internal insecurity. In all five examples, these cash-strapped, heavily indebted nations paid for this military support with resource concessions.

Already there have been public demonstrations in North Kivu advocating for the DRC to supplant UN peacekeepers or the Congolese armed forces (FARDC) with Wagner. Kinshasha is certainly aware of both the security issues in the Kivus coupled with the weaknesses of the FARDC, and it’s something that’s likely on Yevgeny Prigozhin’s mind already. Wagner is already in at least six other African countries, while Russian influence operations have occurred in many more, often in unstable but resource-rich countries.

Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi’s security problems aren’t limited to Rwanda; domestic political rivals like Moïse Katumbi and former President Joseph Kabila have support both regionally and within the FARDC. Coupled with external support from Russia, either, or both could mount a dangerous grab for power, as has happened repeatedly in the DRC’s history. Tshisekedi desperately needs to find a way to solve his internal security problems and frustrate further Rwandan aggression; unfortunately, his current forces clearly lack the ability to do so. Without taking steps to quickly build defence-capacities immediately, he risks being the fourth Congolese president to be removed from office by force.

Modern Rwanda has an established history as a reliable partner for major Western powers, coupled with nearly universal admiration for the resilience of its people who faced an atrocity of unimaginable proportions. However, Kagame’s history with the West shouldn’t preclude Western governments from taking a hard line with Kigali when necessary – and in this case, that means actively discouraging another Rwandan invasion of the DRC.