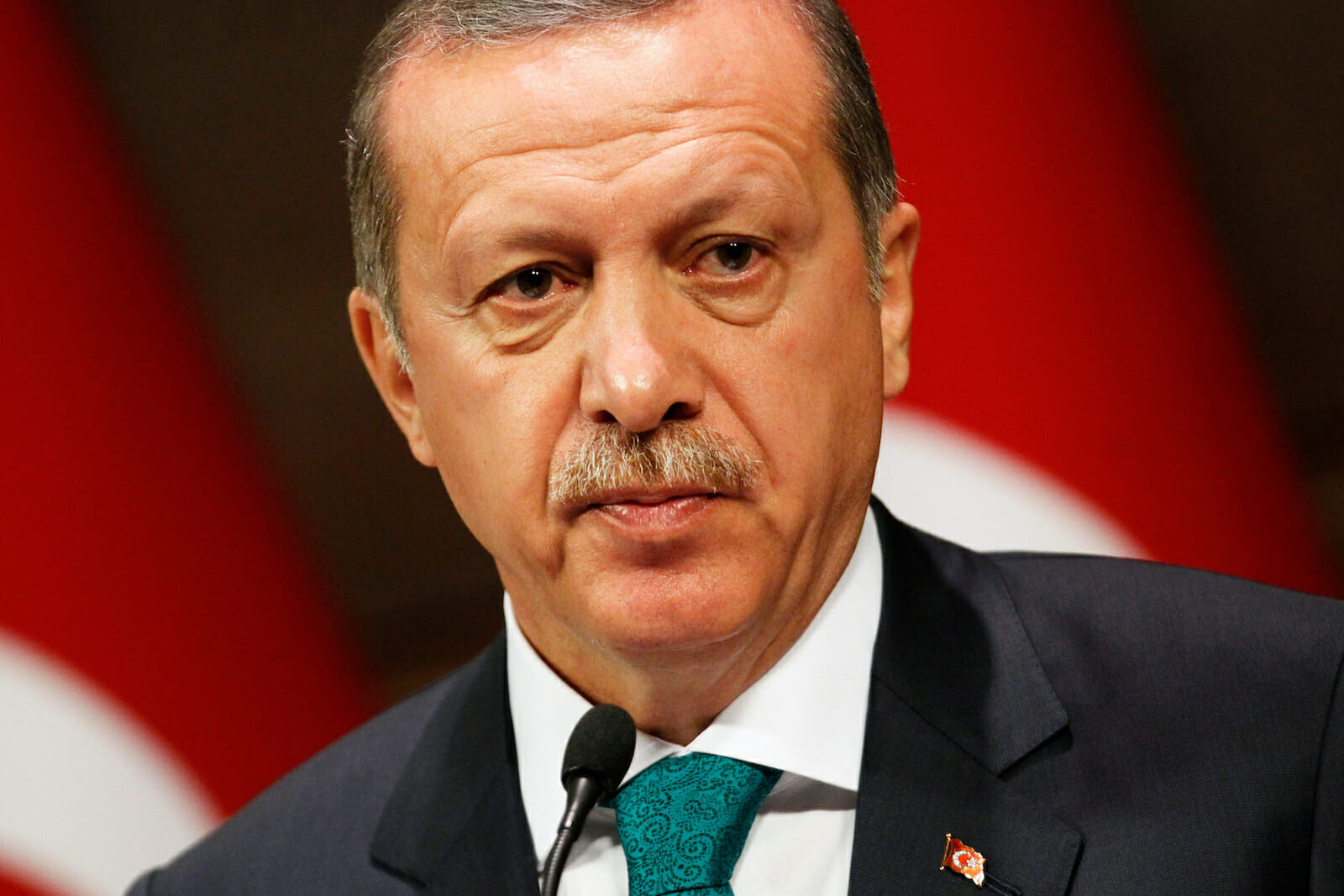

A Wounded Erdogan Could Be Dangerous

For the second time in a row, Turkish voters have rebuked President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s handpicked candidate for the mayoralty of Istanbul, Turkey’s largest and wealthiest city. The secular Republican People’s Party (CHP) candidate, Ekrem İmamoğlu, swamped Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) candidate Binali Yıldırım in an election that many see as a report card on the president’s 17 years of power.

So what does the outcome of the election mean for the future of Turkey, and in particular, its powerful president? For starters, an internal political realignment, but also maybe a dangerous foreign policy adventure.

Erdogan and his Party have been weakened politically and financially by the loss of Istanbul, even though the president did his best to steer clear of the campaign over the past several weeks. Since it was Erdogan that pressured the Supreme Election Council into annulling the results of the March 31 vote, whether he likes it or not, he owns the outcome.

His opponents in the AKP are already smelling blood. Former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, who Erdogan sidelined in 2016, has begun criticizing the president’s inner circle, including Berat Albayrak, his son-in-law and current Finance Minister. There are rumors that Davutoğlu and former deputy Prime Minister Ali Babacan are considering forming a new party on the right.

Up until the March election that saw the AKP and its extreme nationalist alliance partner, the National Movement Party (MHP), lose control of most the major cities in the country, Erdogan had shown an almost instinctive grasp of what the majority of Turks wanted. But this time out the AKP seemed tone deaf. While Erdogan campaigned on the issue of terrorism, polls showed most Turks were more concerned with the disastrous state of the economy, rising inflation, and growing joblessness.

The “terrorist threat” strategy—shorthand for Turkey’s Kurdish minority—not only alienated conservative Kurds who reliably voted for the AKP, but forced the opposition into a united front. Parties ranging from the leftist Kurdish People’s Democratic Party and the Communist Party to more conservative parties like the Good Party withdrew their candidates from the Istanbul’s mayor’s race and lined up behind the CHP’s İmamoğlu.

The AKP—long an electoral steamroller—ran a clumsy and ill-coordinated campaign. While Yıldırım tried to move to the center, Erdogan’s inner circle opted for a hard right program, even accusing İmamoğlu of being a Greek (and closet Christian) because he hails from the Black Sea area of Trabzon that was a Greek center centuries ago. The charge backfired badly, and an area that in the past was overwhelmingly supportive of the AKP shifted to backing a native son. Some 2.5 million former residents of the Black Sea live in Istanbul, and it was clear which way they voted.

So what does the election outcome mean for Turkish politics? Well, for one, when the center and left unite they can beat Erdogan. But it also looks like there is going to be re-alignment on the right. In the March election, the extreme right MHP picked up some disgruntled AKP voters, and many AKP voters apparently stayed home, upset at the corruption and the anti-terrorist strategy of their party. It feels a lot like 2002 when the AKP came out of the political margins and vaulted over the rightwing Motherland and True Path parties to begin its 17 years of domination. How far all this goes and what the final outcome will be is not clear, but Erdogan has been weakened, and his opponents in the AKP are already sharpening their knives.

An Erdogan at bay, however, can be dangerous. When the AKP lost its majority in the 2015 general election, Erdogan reversed his attempt to peacefully resolve tensions with the Kurds and, instead, launched a war on Kurdish cities in the country’s southeast. While the war helped him to win back his majority in an election six months later, it alienated the Kurds and laid the groundwork for the AKP’s losses in the March 2019 election and the Istambul’s mayor’s race.

The fear is that Erdogan will look for a crisis that will resonate with Turkish nationalism, a strategy he has used in the past.

He tried to rally Turks behind overthrowing the government of Bashar al-Assad in Syria, but the war was never popular. Most Turks are not happy with the 3.7 million Syrian refugees currently camped in their country, nor with what increasingly appears to be a quagmire for the Turkish Army in Northern and Eastern Syria.

In general, Turkey’s foreign policy is a shambles.

Erdogan is trying to repair fences with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates because he desperately needs the investment that Gulf monarchs can bring to Turkey. But the price for that is a break with Iran and ending his support for the Muslim Brotherhood. While the Turkish president might be willing to dump the Brotherhood, Erdogan feels he needs Iran in his ongoing confrontation with the Kurds in Syria, and, at least at this point, he is unwilling to join Saudi Arabia’s jihad on Tehran.

In spite of the Turkish president’s efforts to normalize ties with Riyadh, Saudi Arabia recently issued a formal warning to Saudi real estate investors and tourists that Turkey is “inhospitable.” Saudi tourism is down 30 percent, and Turkish exports to Saudi Arabia are also off.

Erdogan is also wrangling with the US and NATO over Ankara’s purchase of the Russian S-400 anti-aircraft system, a disagreement that threatens further damage to the Turkish economy through US-imposed sanctions. There is even a demand by some Americans to expel Turkey from NATO, echoed by similar calls from the Turkish extreme right.

Talk of leaving NATO, however, is mostly Sturm und Drang. There is no Alliance procedure to expel a member, and current tensions with Moscow means NATO needs Turkey’s southern border with Russia, especially its control of the Black Sea’s outlet to the Mediterranean.

But a confrontation over Cyprus—and therefore with Greece—is by no means out of the question. This past May, Turkey announced that it was sending a ship to explore for natural gas in the sea off Cyprus, waters that are clearly within the island’s economic exploitation zone.

“History suggests that leaders who are losing their grip on power have incentives to organize a show of strength and unite their base behind an imminent foreign threat,” writes Greek investigative reporter Yiannis Baboulias in Foreign Policy. “Erdogan has every reason to create hostilities with Greece—Turkey’s traditional adversary and Cyprus’s ally—to distract from his problems at home.”

Turkey has just finished large-scale naval exercises—code name “Sea Wolf”— in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean and, according to Baboulias, Turkish warplanes have been violating Greek airspace.

Cyprus, along with Israel and Egypt, has been trying to develop Cypriote offshore gas resources for almost a decade, but Turkey has routinely stymied their efforts. The European Union (EU) supports the right of Cyprus to develop the fields, and the EU’s foreign policy head, Federica Mogherini, called on Turkey to “respect the sovereign rights of Cyprus to its exclusive economic zone and refrain from such illegal actions.” While Mogherini pledged “full solidarity” with Cyprus, it is hard to see what the big trade organization could do in the event of a crisis.

Any friction with Cyprus is friction with Greece, and there is a distinct possibility that two NATO members could find themselves in a face off. Erdogan likes to create tensions and then negotiate from strength, a penchant he shares with US President Donald Trump. While it seems unlikely that it will come to that, in this case, Turkish domestic considerations could play a role.

A dustup with Ankara’s traditional enemy, Greece, would put Erdogan’s opponents in the AKP on the defensive and divert Turks attention from the deepening economic crisis at home. It might also allow Erdogan to use the excuse of a foreign policy crisis to strengthen his already considerable executive powers and to divert to the military budget monies from cities the AKP no longer control.

Budget cuts could stymie efforts by the CHP and left parties to improve conditions in the cities and to pump badly needed funds into education. The AKP used Istanbul’s budget as a piggy bank for programs that benefited members of Erdogan’s family or generated kickbacks for the Party from construction firms and private contractors. Erdogan has already warned his opponents that they “won’t even be able to pay the salaries of their employees.” The man may be down but he is hardly beaten. There are turbulent times ahead for Turkey.