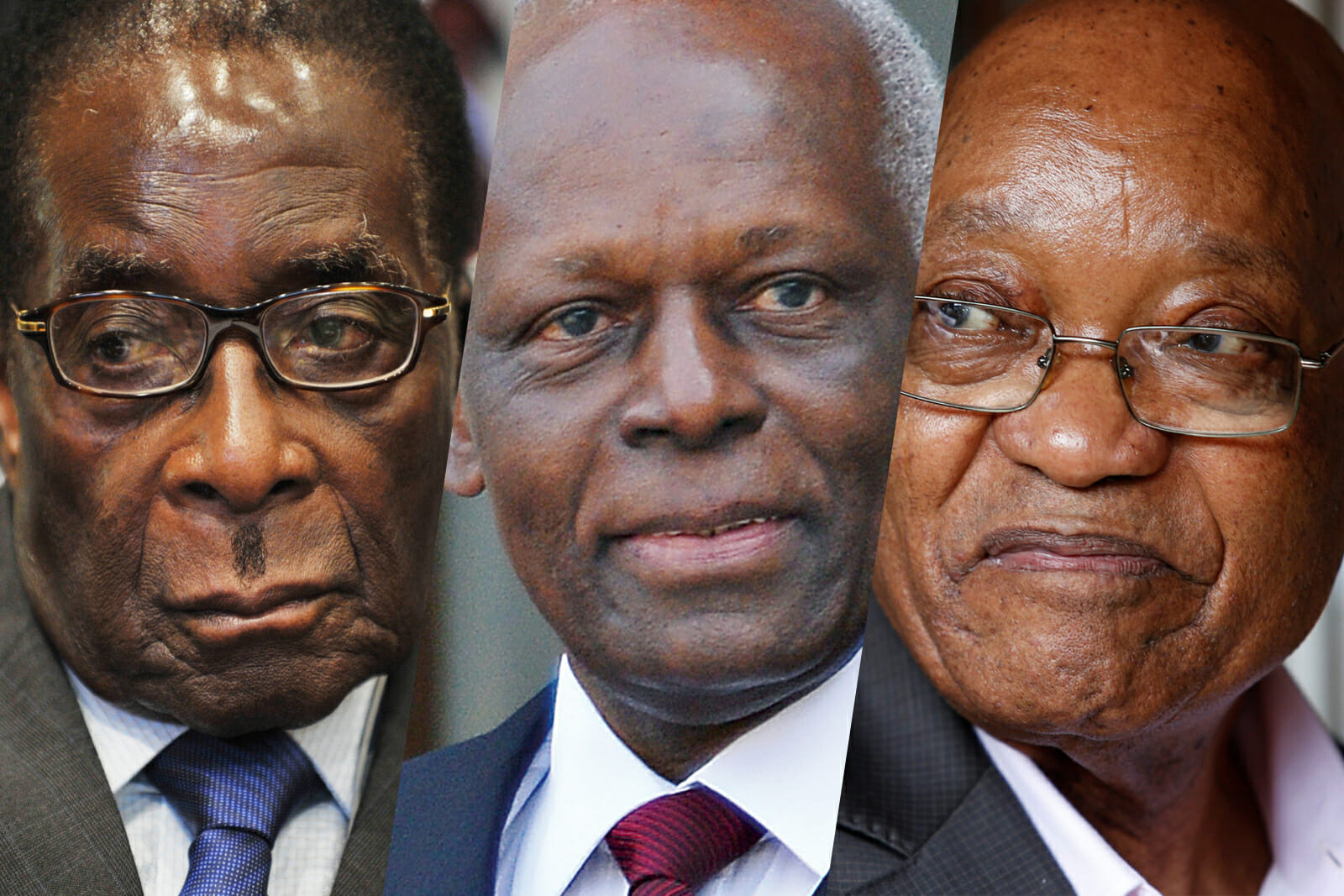

Africa’s ‘Big Men’ Aren’t Going Anywhere

Southern Africa’s string of leadership changes over the last few months was met with elation from the domestic and international press. In Angola, long-serving leader Jose Eduardo dos Santos transitioned power to a new president for the first time in 38 years. A few months later Robert Mugabe, then-dictator of Zimbabwe, was removed from power in a coup led by the military. To complete the triumvirate of retirees, South African President Jacob Zuma was ousted by his party in December after a number of corruption scandals dating before and during his presidency. While these events are certainly cause for celebration, how much have things really changed?

To many observers, the sudden exodus of two dictators and a dictator-in-waiting might signal the waning of authoritarianism in southern Africa. “This very public drama” writes Patrick Smith in the March editorial for The Africa Report, “may be the final act for the ‘Big Man’ theory of power.”

And while it is tempting to view the collapse of corrupt and autocratic leadership in southern Africa as a revolution in African affairs and a new wave of democratization, it is no such thing. Now that the dust has settled, the status quo has been maintained, and “Big Men” along with it.

In all three cases, the transitions of power did not even leave the ruling party. Zuma’s own African National Congress (ANC) elected his replacement, Cyril Ramaphosa, without having to face a general election until 2019. Dos Santos orchestrated the transfer of power to João Lourenço, a younger member of the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), a party that he will head until at least 2019 despite leaving the presidency. While the coup d’état in Zimbabwe was more dramatic, Mugabe was overthrown and ultimately replaced by his fellow party members. The country is now led by Emmerson Mnangagwa and a coterie of serving and retired generals, all of whom have been with Mugabe’s Zimbabwe African National Congress – Popular Front (ZANU-PF) for decades.

The prospects of a new ruling party for any of these countries looks bleak. Opposition parties in all three countries are mobilizing in response to the power changes, but are unable to meaningfully challenge the ruling order ahead of their respective elections.

In Zimbabwe the main opposition leader, Morgan Tsvangirai, passed away on February 14 after a long battle with colon cancer. The unfortunate news leaves the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) without its charismatic and popular leader at a key time in Zimbabwean politics. Between the loss of Tsvangirai and the military’s apparent support for ZANU-PF, there is little indication that the next round of elections will go the opposition’s way.

Things are not much different in Angola. Even with the loss dos Santos, the MPLA still enjoys a thorough monopoly on Angolan politics since the end of the Angolan Civil War in 2002. Despite Lourenço’s supposed attempts to tackle corruption, these efforts have mostly taken the form of removing those in government personally supportive of dos Santos, including the former President’s daughter. Few in Angola view the change of leadership as a truly democratic move, and opposition parties are too scattered to meaningfully oppose the MPLA on a national level.

In South Africa, the ANC remains a majority party with strong foundations, despite losing a lot of momentum and political legitimacy as a result of Zuma’s presidency. Opposing parties like the Democratic Alliance (DA) are poised to make gains in the next elections, but are far from toppling the ANC altogether.

Should Ramaphosa prove to be a competent enough leader and redress many of the grievances generated under Zuma, South African voters will stay with the party come elections in 2019. He has already begun to rebuild a sense of trust by cancelling a controversial project under Zuma to build a Russian nuclear power plant, citing its exorbitant cost.

There are, of course, just as many bright spots in Africa. The events of Zuma’s presidency and bloodless ouster, while concerning, can be seen as a successful stress test of South Africa’s democratic institutions in the face of a potential power grab by the executive. Many of the countries that made democratic transitions in the late 90’s and early 2000s have remained stable and democratic. Some, such as Liberia have successfully held fair elections in recent years and show little sign of serious political turbulence in the near future. But these success stories do not characterize Angola or Zimbabwe, where new leadership does not necessarily mean new modes of governance.

The sound and fury over the past few months signified nothing. What we have seen over the last few months is not a new beginning for South Africa, Angola, or Zimbabwe, nor a new era for African politics as a whole. The political structures kept these leaders as heads of state for so long are still in place, even if Zuma, dos Santos, and Mugabe are not. That three big men have fallen in a short period unfortunately means very little to the populations who now endure the same autocracy with new faces.