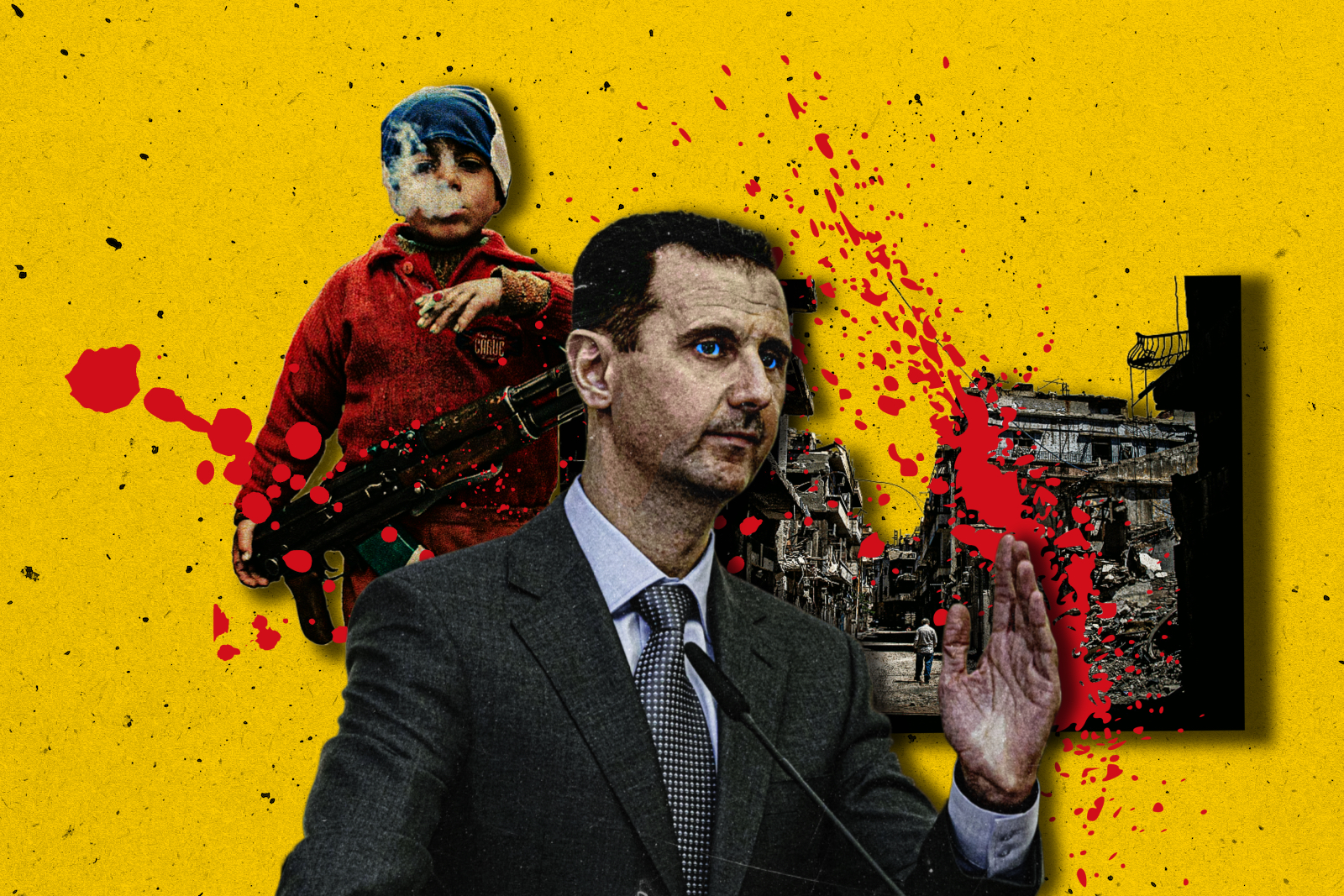

After 13 Years, Syria’s Bloody War Shows No Sign of Letting Up

On March 15, Syria’s civil war entered its thirteenth year and another one in which the chances for long-term and sustainable peace look unlikely. Despite some reduction in violence in recent years, a peaceful resolution remains distant, even as the country’s population remains trapped in a humanitarian crisis.

Last year, the UN estimated that more than 350,000 people had died as a direct result of the war during its first decade. But that figure did not include many more thousands who may have died indirectly, through a lack of access to healthcare, food, or water. Out of a population of more than 22 million in 2011, Syria has seen 6.7 million people internally displaced and 6.6 million leave the country to become forever refugees.

The war was part of the wider Arab uprisings taking place at the time. Initially, protestors took to the street to demand change. When the regime, headed by President Bashar al-Assad, cracked down on them, others took note and took up arms. What began as a revolutionary movement evolved into an armed conflict. Moreover, it did not stay within its borders, with both the regime and its opponents acquiring support from the outside.

While Assad’s hold on power looked unsteady during the first years of the conflict, by the second half of 2010 the regime had recovered sufficiently to regain around 70 percent of the national territory, with the remainder controlled by armed groups, mostly in the north.

The regime’s recovery had a number of consequences. One has been the emergence of a new economic elite and the strengthening of Assad and his closest associates. Increasingly, Damascus has also sought to take advantage of aid that has come into the country, to control its flow and to ensure that as little humanitarian assistance finds its way into opposition hands. Assad’s determination to do this has grown as the sanctions against the regime have grown and tightened, prompting Assad to find different ways to siphon off financial aid from the United Nations and others.

Politically, Assad is in a relatively strong and secure position, especially when compared to the early years of the war. Consequently, he has been less inclined to engage in peace talks with the opposition through the roadmap set out by the international community through UN Resolution 2254 back in 2015. It has helped Assad that beyond the resolution’s general principles, there is little additional international consensus; some states support Assad’s rule while others do not. The absence of agreement on how to move forward means that the status quo of no war, no peace persists, even as Geir Otto Pedersen, the UN’s Special Envoy, has tried to keep the UN roadmap alive in his contacts with different parties within and outside Syria.

Pedersen’s efforts though are being eclipsed by other, more recent actions within the Arab world. Increasingly, they point to Assad’s normalization. In 2011, Syria was cast out of the Arab League. But at the end of 2018, both the UAE and Bahrain reopened their embassies in Damascus. Then, in 2021, Jordan’s King Abdullah spoke to Assad by phone for the first time in a decade. Algeria then tried to persuade other Arab states to let it invite Assad to the Arab League summit which it hosted in November 2022.

The Algerian effort proved a step too far. As of yet, there has been no broad agreement for Syria’s return. Nevertheless, the willingness of Arab leaders to normalize relations with Assad, especially those from the Gulf, highlights a number of motivations for doing so. They hope that by engaging Damascus they can encourage it to adopt a more moderate stance and engage with the opposition in exchange for financial assistance and reconstruction aid. Not only would that curb the rise of radical groups like ISIS that emerged over the past decade, but it could also reduce Iran’s influence while also persuading Syrian refugees across the region to return home.

Yet while normalization may help to reduce the conflict and its spillover effects, it may fail on other grounds. Any rehabilitation of Assad without an acknowledgment of what his regime has done ignores the grievances of those Syrians who initially protested and later took up arms against the regime. There is also a risk that Assad may not be held accountable for the war crimes committed by his regime and its partners. This could sow the seeds of resentment and dissent.

Meanwhile, even as a peaceful settlement remains beyond reach, Syrians face an ongoing humanitarian crisis which has been exacerbated by a number of other developments in recent years. They include the COVID pandemic and the devastating earthquake that hit southern Turkey and northern Syria last month as well as the financial collapse taking place in Lebanon. In the case of the first two, the absence of decent healthcare facilities after a decade of fighting has made an already bad situation even worse. Meanwhile, the breakdown of Lebanon’s banking system and the wider economy has adversely affected many Syrians who would otherwise have used its banks to shelter capital or traveled to the country to escape poverty and find work.

The Syrian conflict and its resolution remain a daunting challenge. While humanitarian aid is necessary, it cannot replace a more permanent resolution to the conflict. The involvement of external forces, the ongoing fighting, and a lack of accountability for war crimes are just some of the obstacles to a political solution. The normalization of relations with the Assad regime may have its benefits, but it also carries risks, and the grievances of the Syrian people must not be overlooked if a lasting peace is to be achieved.