After Guelleh’s Election, Much of the Same for Djibouti

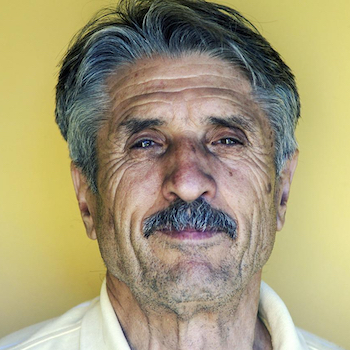

On the 10th of April, the small but strategically important country of Djibouti on the Horn of Africa re-elected Ismaël Omar Guelleh, the incumbent, as president for the fifth time, in what was apparently a landslide victory. Guelleh won 98.5% of the votes, while his only challenger received just under 5,000, meaning the 73-year-old will now hold office for another term.

But all is not what it seems. Upon closer inspection, Guelleh’s victory against the political neophyte salesman, Zakaria Ismaël Farah, is undermined by the fact that the result of the general election was a fait accompli from the get-go.

A bogus election

The outcome is hardly surprising given Guelleh’s penchant for dishonest behaviour. Guelleh’s opponent deemed the 177,391 votes for Guelleh “far from reality”––not an unreasonable assertion given that no law enforcement was provided by the government during his campaign, rendering political rallies unfeasible and forcing Farah to stay at home for his own safety. The lack of independent media outlets in the country only compounded the opposition’s difficulties in campaigning successfully.

Moreover, international observers have dismissed Farah’s candidacy as a “masquerade as surreal as it is absurd,” instead only serving to legitimise the presidential elections. Indeed, the system was so skewed from the outset that a coalition of Djibouti’s main political opposition, the Union pour le Salut National (USN), boycotted the elections outright, in protest. However, this month’s elections are by no means the first time that Guelleh has leveraged his position to suppress political resistance for the sake of holding on to power.

A long history of authoritarian politics

Ismaël Omar Guelleh has ruled the country since 1999 when he was handpicked by his uncle, Hassan Gouled Aptidon, the outgoing former president, himself at the helm for twenty years since the country’s liberation from French rule. Ever since his election, the president’s malefactions have oftentimes come to the attention of the international community. As part of the UN’s Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of Civil Society in 2018, a report found that the 14 recommendations given after the 2011 review had been all but entirely ignored by Djibouti’s government. The authors called for the government to “take immediate steps to meaningfully engage in the UPR process and to improve its human rights legal framework and practices.” But, alongside opposition politicians, human rights defenders, journalists, and even artists have been consistently targeted and harassed for criticising Guelleh’s leadership.

Even so, for a brief moment in the summer of 2020, freedom of expression in the country seemed possible when civilians took to the streets in a peaceful protest against repression. This rare outburst of civil disobedience was triggered by the unjust imprisonment of the Djiboutian Air Force Lieutenant Fouad Youssouf Ali who had blown the whistle on corruption and clan-discrimination of the ruling party. But by October the protest was brutally quashed by police using excessive force, including live ammunition.

The Chinese connection

While the protests went largely unnoticed in much of the world, long-standing geopolitical issues have been a constant thorn in the side of Western powers stationed in Djibouti. The manoeuvre with the biggest impact on these has been President Guelleh’s pivot towards China and the massive cash injections Beijing provides. As a crucial trade and military location, Guelleh’s 2016 decision to allow China to build a military base there, in close proximity to that of American and French bases, was met with consternation––a decision no doubt made easier by a ready influx of Chinese cash under the country’s gargantuan Belt and Road Initiative.

Not only has the country’s Chinese debt since soared to more than 70% of its GDP, but the partnership with Beijing has also seen Guelleh tearing up long-standing business contracts with national and international partners, in favour of China. A case in point is that of Djibouti’s port bordering the Red Sea, one of the country’s most precious assets. In what has been described by observers as a bid to curry favour with the Chinese, Guelleh turned on prominent Franco-Djiboutian businessman Abourahman Boreh who had secured investment from Dubai for the port and became the former chairman of the Djibouti Ports & Free Zones Authority.

During his time as supervisor and adviser to the government, Boreh had called out the regime’s corruption amid refusing to assist Guelleh in changing the constitution to enable him to remain in office. As a consequence, Guelleh had Boreh’s assets frozen and charged him with allegations of fraud and bribery. Boreh was cleared of all charges by a London court in 2016, but the settlement did nothing to threaten Guelleh’s position.

Then, in 2018, Guelleh seized the Doraleh Container Terminal, run by Dubai’s DP World, one of the world’s largest port operators, before handing it over to the giant state entity China Merchant Port Holdings. The company subsequently took the case to the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA), claiming damages and the restitution of the original port contract.

Guelleh is sticking to his course

Five subsequent arbitration rulings in DP World’s favour followed, with the latest occurring in January this year, ordering Djibouti to return the company’s rights as agreed under a 2006 concession agreement and cough up $385 million in damages. In April this year, DP World also filed another $210.2 million in damages for revenue losses from Djibouti. However, the country has yet to pay any heed to the decision of this international court––a fact which won’t go unnoticed by foreign investors.

The likelihood of Djibouti’s reconciliation with former partners and a rolling back of the dangerous dependence on China is less likely than ever after last week’s vote. Although Guelleh’s re-election was the inevitable outcome of a corrupt system, the outcome is nonetheless a heavy blow to the freedom of the population. A 2010 revision of the country’s constitution forbids a sixth term as president, but only time will tell if this is truly Guelleh’s last hurrah.