Alexander Hinton on White Nationalism’s Long Arc

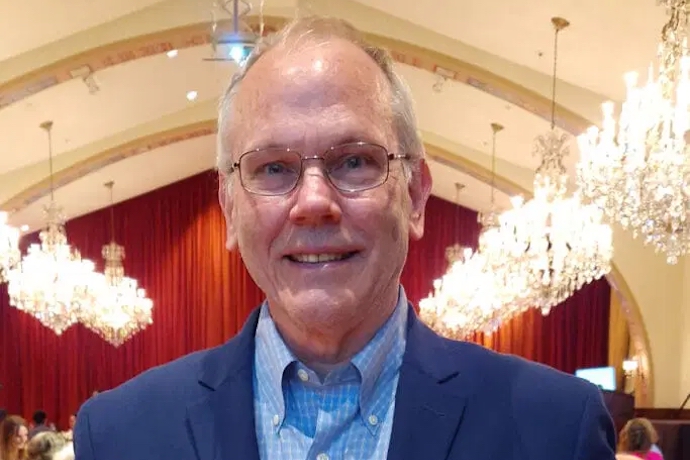

Alexander Hinton is a distinguished professor of anthropology at Rutgers University and director of the Center for the Study of Genocide and Human Rights. A UNESCO Chair on Genocide Prevention, he is a leading scholar of political violence, white nationalism, and atrocity crimes.

In It Can Happen Here, Hinton traces the continuity of white power movements in the United States and situates them in global patterns. He shows how grievance, demagogic rhetoric, and social-media ecosystems mobilize fear, draws resonances with Nazi propaganda and other extremist ideologies, and warns of democratic backsliding. His earlier book, Why Did They Kill? Cambodia in the Shadow of Genocide probes the historical roots of extremism and structural racism.

Hinton earned his Ph.D. from Emory University in 1997 and lectures internationally. Professor Hinton, thanks for joining us today.

Alexander Hinton: Thank you so much. It’s a pleasure to meet you as well.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: When you map the evolution of white nationalism in the United States, what through-lines stand out? Today it sits at the center of cultural and political debate, even though it hasn’t always been named as such.

Hinton: Yes. The context depends on where we are in the world, as historical connections and interactions exist. One example is Nazi Germany, where ideas moved back and forth, influencing white supremacist ideology.

More recently, in relation to my book It Can Happen Here, I testified at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal in Cambodia. This UN-backed hybrid tribunal consists of both UN and Cambodian personnel. I testified there in 2016, around the same time that Donald Trump, then a presidential candidate, was running for office. Much of his rhetoric echoed themes I write and teach about.

I am not suggesting that Trump was comparable to Pol Pot or Hitler in any way. However, his rhetoric—including dehumanization, references to enemy invaders, and discussions of migrant caravans—is part of a historical pattern. These narratives frequently appear in contexts of mass violence, genocide, and atrocity crimes. Recognizing this, I thought, “This is something to watch closely.”

At the same time, many people were making the false equivalence of claiming that “Trump is Hitler.” At one point, this was a viral meme while I was testifying. These discussions were circulating widely, and I was already working on a book about my experiences at the tribunal, which later became Anthropological Witness.

Of course, Trump won the election. We entered what I refer to as Trump 1.0, followed by events such as Charlottesville and the Unite the Right rally in 2017. That rally was a turning point in public perception. Richard Spencer’s “Heil Trump” salute was widely seen, and people began to recognize that elements of the white power movement had gained visibility within his support base.

During Trump 1.0, most of his supporters tended to be older, white, religious, and less formally educated. It is always important to specify formal education because education exists in different forms, but this was a demographic where he had substantial support.

He also received backing from figures such as David Duke, though it is crucial to clarify that this was not the core of his support. However, the white nationalist element was present. This became undeniable in Charlottesville, where marchers chanted, “Jews will not replace us” and “You will not replace us.”

These streets—whose streets? Our streets. But the discourse of “Jews will not replace us” caught everyone’s attention at the time. It was a while back.

Some people may not even know about it at this point. Still, it was certainly an international event as well as a domestic one. A series of white power shootings then followed that.

We had Robert Bowers and the Tree of Life synagogue attack. We had the Walmart shooting in El Paso. There was one in Southern California. Moving forward into the present, we had the Buffalo Tops shooting. Suddenly, there were multiple attacks. Bowers’ shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue, in particular, drew much attention.

So, I decided to take a deep dive into my book, It Can Happen Here, which argued that what many saw as a spectacular aberration—embodied by Trump 1.0 and Donald Trump—was, in fact, not at all discontinuous with U.S. history. I don’t go into this in great detail, but obviously, it also ties into global history.

The first part of the book traces the history of white power in the U.S., going back to the founding of the country and, moving forward, examining how systemic white supremacy has operated.

Later, I wrote an article discussing one way to conceptualize this history: through the lens of micro-totalitarianism. This framework helps capture the reality that while the U.S. has functioned as a democracy for a significant portion of its population, within that same system, there have been people who have lived under conditions resembling totalitarian rule.

For example, enslaved peoples—and later, Black Americans during Jim Crow—experienced a level of control over their lives that mirrored regimes like the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. The state and local authorities exercised overwhelming power over what individuals could say, do, think, and learn.

The book’s argument is that it can happen here. It has happened here. Can it happen again?

Of course, it can happen again.

If you think about it, only in the 1960s did the U.S. begin to break away from predominantly white power structures. Of course, the U.S. is not a monolith—there is a great deal of variation within it. However, the civil rights movement ruptured this historical pattern. Ironically, some gains from that era are now under attack in the U.S.

The vast majority of U.S. history has been characterized by white power and white supremacy. If you visualize it on a timeline stretching from Jamestown in the early 1600s to the present, the overwhelming portion of that history consists of enslavement, the dispossession of Native American peoples, and systemic racial injustice.

I emphasize that acknowledging history means looking within ourselves. All of us have good aspects and flawed aspects. The U.S. has achieved many great things, but there is also a shadow side.

To invoke Carl Jung, we all have a shadow, and nations do as well. One of the most disconcerting and bizarre arguments I’ve encountered is that we should ignore or avoid engaging with this side of history. However, just as an individual’s healthy growth requires acknowledging their strengths and flaws, nations must do the same to move forward.

This debate continues to play out in the U.S. today.

It was interesting, coincidentally, to see Elon Musk recently argue that Germany should forget about the past. The argument that people should not feel guilty or personally responsible as a major part of their lives makes sense. However, the idea that we should ignore the fact that certain groups have been dispossessed—while attempting to remedy past abuses without placing blame—is more complicated.

In the U.S., much of this has played out with younger white male voters. That is a longer discussion. But ultimately, we have to confront the shadow side of history. To answer your question, yes, this has been a reality in the U.S. for most of its history. While some aspects remain interwoven with society today, things are much better than 40 or 50 years ago.

Trump is not an exception. He is certainly spectacular because he knows how to control a crowd and command attention. However, what he represents is not a break from U.S. history—it is continuous with it.

Jacobsen: In your view, how does political rhetoric—the themes you’ve outlined—work to legitimize white-nationalist movements and animate what you call their Jungian “shadow sides,” bringing once-fringe ideas into mainstream conversation?

Hinton: Yes, that is an interesting question. Of course, this is obvious, but it bears repeating: the advent of social media and global interconnection has amplified and accelerated ideas that existed long before.

White power groups were among the first users of the Internet, and many people are unaware of this. They made global connections early on and were well-positioned by the time we entered the smartphone era, starting with the iPhone in 2007, which brought massive changes.

The reason I mention this is that we now have different ideological “bubbles”—though “silos” might be a more accurate term—where communities gather and reinforce one another’s views. One well-known example is 4chan, a notorious hub for white power extremists.

These groups develop their own coded language and references, and we often see ideas move from these underground spaces into mainstream discourse. A clear example is how language from platforms like 4chan, Telegram, and Gab gradually surfaced on larger platforms such as Facebook and X (formerly Twitter).

For instance, during the last election cycle, there was a JD Vance “pedophiles” trope that emerged. That narrative originated in extremist circles on 4chan and Telegram before surfacing in public demonstrations—such as marches in Springfield—where it gained visibility. Eventually, it bubbled up into mainstream conservative discourse, reaching figures like JD Vance himself.

This phenomenon is tied to a broader strategy within far-right and white power extremist circles: shifting the Overton Window. The Overton Window refers to the ideas considered acceptable in mainstream discourse. Over time, what was once considered fringe or extremist can become normalized through repeated exposure.

Much of the rhetoric that is now common in political discourse—including on platforms like X—was once confined to far-right extremist spaces. Elon Musk, for example, frequently tweets narratives that align with these ideas.

Take the concept of the “Great Replacement.” It has been phrased in different ways, but at its core, it suggests that non-white immigrants are intentionally replacing white Christians in the U.S. There is a factual element in the sense that demographics in the U.S. are changing, and the white population is projected to lose its majority in the next 20 to 30 years.

However, in extremist circles, this demographic shift is framed as intentional—as if there is a coordinated effort behind it. That naturally leads to the question: Who is orchestrating this?

At the mainstream conservative level, the answer tends to be “Democrats.” But within white power extremist discourse—going back to Charlottesville and earlier—the belief is that Jews are orchestrating it.

Everything ties into the belief that there is a plot to subvert white power and ultimately destroy white people. This brings us to the idea of white genocide, which predates much of the recent discourse.

In 2015, during the European immigration crisis, we began to see the widespread circulation of replacement theory narratives. This rhetoric was later imported into the U.S. Still, the underlying trope had been there long before in the form of the white genocide theory.

By the time we get to Robert Bowers, the perpetrator of the Tree of Life synagogue shooting, he has fully embraced this ideology. His motivation was the belief that Jews were helping immigrants “pour into” the U.S. That was his key justification.

On his Gab homepage—a far-right extremist platform with strong Christian nationalist leanings—Bowers had several disturbing elements. Among them was an image of a radar gun, which prominently displayed the number 1488.

At first, this number might seem odd, but once you examine its symbolism, a pattern emerges. 1488 is a combination of two elements: 14 Words – A white supremacist slogan coined by David Lane, a member of The Order, a white nationalist terrorist group from the 1980s. 88 – A reference to “Heil Hitler” (H being the eighth letter of the alphabet).

The Turner Diaries deeply influenced the Order itself. This novel has been called the “bible” of white supremacy. The book tells the story of white people rising against what they see as an existential threat, forming a group called The Order to eliminate non-whites and so-called “race traitors.”

This novel inspired real-world actions. The actual Order, a violent extremist group, emerged in the 1980s, robbing banks and engaging in other criminal activities to fund their white nationalist cause. There was even a film adaptation of The Turner Diaries released at the end of 2024.

David Lane, one of The Order’s members, was arrested and imprisoned, where he later wrote the White Genocide Manifesto. In this document, he ends with 14 Words, which I will not repeat here, but the essence is a call to protect white children from what he describes as a nefarious plot to wipe out the white race.

So, when Bowers displayed 1488 on his Gab profile, he was signalling deep ideological alignment with this extremist lineage. This illustrates the connection between extremism and political discourse.

What has happened in recent years—intentionally—is that far-right groups have sought to mainstream these ideas. This includes groups one step removed from the “hard” far-right, such as the so-called alt-right, which gained visibility during the Charlottesville rally.

The alt-right has heavily promoted the idea of metapolitics, which argues that the battle is not fought through physical violence but through the control of hearts and minds. This is where cultural narratives come into play.

A major talking point within these circles is cultural Marxism. This conspiracy theory claims that Jewish intellectuals from the Frankfurt School came to the U.S. with the intent of brainwashing the population. This theory, like many far-right narratives, often ties back to anti-Semitic tropes about Jews orchestrating societal change.

The goal of these extremists is to shift the Overton Window—the range of socially acceptable discourse—by normalizing once-fringe ideas.

This tactic has been highly effective. Using humour, irony, and gradual exposure, ideas once confined to extremist circles have entered the mainstream discussion.

For example, replacement theory, which was once framed explicitly as white genocide, has now been repackaged and is widely discussed. The core idea remains the same, but the language has been adapted to make it more palatable for broader audiences.

I can go to Telegram right now and find videos of far-right extremist groups protesting immigrants in hotels. There is one group, in particular, I am thinking of that carries signs explicitly referencing “replacement.”

At the same time, this rhetoric appears at the highest levels of government. JD Vance, for example, has alluded to the idea of “Haitian immigrant invaders.” He did not explicitly use the term “replacement.” Still, his language framed these immigrants as savages—suggesting that they eat pets, that they do not understand American customs, and that they do not belong. The implication was clear: they are not fully human.

We have seen this kind of rhetoric before and know where it leads. While Vance himself may not have made direct connections to white nationalist narratives, far-right extremist groups certainly did. They took his remarks and amplified them within their communities.

This is part of a broader strategy. By shifting the Overton Window, you gradually make formerly unacceptable ideas more mainstream. From the perspective of these groups, that is how you advance your cause.

Jacobsen: We’ve covered history and ideology, but what about risk factors? Given today’s rhetoric and the broader ideological climate, how likely is it that this discourse escalates—not merely into mass protests, a constitutionally protected right in the United States—but into targeted intimidation, violence, vandalism, destruction of property, or Americans doing harm to other Americans?

Hinton: That is a great question; the answer depends on when you ask it.

If you had asked in 2020, in the lead-up to the Biden-Trump election, the warning signs would have been there.

For those of us who study atrocity crimes—a term encompassing genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and ethnic cleansing, as well as broader political violence—many indicators of potential mass violence were present.

At that time, the U.S. was experiencing: a global pandemic created instability, an economic crisis further fueled public unrest, and the mobilization of heavily armed far-right groups.

One key catalyst for political violence around the world is a contested election. Historically, contested elections frequently lead to violence, especially in fragile or polarized democracies.

Two of the biggest risk factors that can escalate political violence into crimes against humanity are: a contested election—which we had in 2020, and democratic backsliding also occurred at the time.

Authoritarian regimes tend to be more stable in this regard—unless they deliberately target specific groups. However, democracies are not immune. Suppose you look at the historical treatment of Indigenous peoples in the U.S., for example. In that case, you see state-backed violence occurring within a democratic framework.

The greatest instability occurs when a country moves between political systems—either sliding into authoritarianism or undergoing democratic reform. In 2020, the U.S. experienced significant democratic backsliding, which heightened the risk of political violence.

At that time, I wondered: What if Trump had not been banned from Twitter? Before the January 6th insurrection, Twitter was his primary tool of communication. When the platform removed him, he temporarily lost his direct channel to millions of supporters. There was no Truth Social then, so his ability to escalate tensions was reduced.

I wrote about this in an article for Project Syndicate, analyzing the high potential for violence at that moment. And indeed, we saw January 6th unfold—a violent attempt to overturn a democratic election.

Fast forward to 2020—isolated attacks by mass shooters were, and still are a reality. Undoubtedly, such attacks will continue, even though the U.S. government has ramped up efforts to combat them. However, I expect that response to diminish under Trump 2.0—but that is a different discussion.

During the last election cycle, there was renewed concern about election-related violence and the potential for political conflict. The movie Civil War was widely discussed in this context, and multiple think tanks conducted war game simulations to explore possible crisis scenarios in the U.S.

The potential for unrest was real—not necessarily large-scale mass violence, but certainly protests, civil strife, and individual acts of violence. But then the election happened.

Democrats hesitate to call it a blowout, but that is essentially what it was. While the Republican candidate did not win most of the popular vote, that did not matter—he won all the battleground states. He made massive inroads with nearly every demographic.

Some key numbers: He secured most of the Latino vote, especially among Latino men—around 56-58%. There was a major swing among young white voters. His base expanded, even though his core support remained the same.

This time, the opposition was defeated and unable to regroup significantly—at least for now. That will likely change over time. The primary mobilization against his policies has been through court cases, which are currently the most effective avenue for opposition.

However, the Democratic Party lacks a clear message. They are struggling to articulate a compelling narrative after what happened. One key shift has been in rhetoric around race.

For many conservatives, being called a racist was one of the most politically damaging accusations. That label stung, and it became a unifying grievance among MAGA supporters.

Having attended MAGA events and read numerous MAGA-related books, I can confirm that this sentiment frequently arises. At rallies, Steve Bannon and others openly dismiss accusations of racism, saying things like, “They can call us racist or not racist—who cares?”

The Republicans, using the metapolitics strategy, leveraged this effectively. They weaponized cultural issues, including wokeness and critical race theory, and launched a devastating political attack against Democrats.

When they folded trans issues into this broader critique, it created even greater challenges for the Democrats.

At the same time, inflation and immigration became major voter concerns. The immigration issue, in particular, had shifted geographically—it was no longer perceived as a crisis only at the southern border. Instead, the impact was being felt in cities, including places like New York, where I live.

The rhetoric around immigration shifted from policy to economic resentment: “why are we giving money to immigrants when we need it here?” and “crime is increasing because of immigration.”

This bread-and-butter combination of economic and immigration concerns was a major factor.

However, what consistently received the loudest applause at MAGA rallies—which I attended as a researcher—were statements about “woke” issues, particularly trans rights.

This became a huge political problem for the Democrats.

One of the major strategic shifts within the Democratic Party over recent years has been a greater focus on identity politics. However, that strategy backfired in this election. Now, the question is: What happens next?

Will Democrats return to their working-class roots? That remains to be seen. Of course, they will continue to advocate for the rights of people of colour and marginalized groups, but the political landscape has shifted.

In many ways, Democrats now face the same kind of political tarnishing that Trump supporters once experienced.

So, there we are. I mention this because there is no immediate threat that Trump needs to deal with—he is in total control. He is sailing along, calling this the golden age, as he puts it.

He says there is now a “light” over the United States and the world because he holds power. So, this is the political reality at the moment.

The risks, aside from mass deportations, include sending people to Guantanamo Bay, detaining individuals in handcuffs, and various other abuses that, according to reports, are already unfolding.

To recap, I explained that this is not a static issue—you have to look at it over time because the situation constantly evolves.

It depends on the context. In 2020, we had one scenario and in the 2024 election, we had another.

However, the threat of election-related violence is now lower—primarily because Trump has consolidated power. He has also expanded his base by adopting a broad anti-DEI, anti-woke, American Marxist discourse, which has politically damaged the Democrats.

As a result, the Democratic Party is in a weakened position. They lack a clear message and are still trying to recalibrate. This means there is no real opposition right now.

There is always the possibility of white power extremist attacks or isolated incidents. Still, there is not much concern in terms of a civil war or large-scale protests escalating into violence.

However, looking ahead to 2028, the situation is far less predictable.

As I mentioned, politics is fluid—things change depending on unforeseen events. We cannot predict the future, but we can anticipate potential risk scenarios: a contested election in which Trump remains in power, but a Democrat appears to have clearly won led to actions that impede a peaceful transfer of power. Trump is running as J.D. Vance’s vice president, mimicking Putin’s political model in Russia.

I do not think that Trump will attempt to secure a third term, as some fear. However, the broader concern remains: what happens during the next power transfer? That is where things could get ugly.

So, in response to your question, I expect more episodic violence, rather than sustained, large-scale unrest. Regarding systemic issues, we will have to monitor the ongoing mass deportations, which have already begun and are expected to escalate.

But here is the key point: Trump’s opposition is now significantly weaker.

It is difficult for his critics to label him and his supporters as “racist” when he has just won the majority of Latino voters. That fact alone diminishes the credibility of those attacks.

With no strong opposition, we will unlikely see any major upheaval soon.

Jacobsen: You’ve described how social media and digital platforms have widened the reach of white-nationalist rhetoric, white identity, and related discourse. For this conversation, I want to draw a clear line between two groups: first, people who regard “white identity” as a cultural descriptor—say, someone of French or Dutch ancestry who values French or Dutch traditions; second, those who adopt a race-based, identitarian political ideology, which is qualitatively different from the first.

These are distinct categories and deserve different analyses. With that distinction in mind, how do social platforms and the broader online ecosystem—recommendation engines, engagement incentives, monetization schemes, influencer networks, and moderation gaps—amplify white-nationalist ideas, shuttle conspiracy theories into wider circulation, and accelerate the slide from cultural identity talk into overt political extremism?

Hinton: Massively.

That is the one-word answer.

This is the “secret sauce,” so to speak. And it goes far beyond white nationalism—it applies to everything.

Rumors spread rapidly.

For example, there have been cases where false rumors involving Dogecoin (Doge), USAID, or other topics have spiked online, gaining momentum even though they are completely untrue.

People exist in silos, where they consume headline-driven information without fact-checking sources. These narratives spread like wildfire, sometimes being deliberately planted by populists and at other times being adopted and amplified by populists after they gain traction.

So, where are people gathering now?

Many left-leaning users have migrated to Bluesky, which means that X (formerly Twitter) has shifted further to the far right than it was before.

I used to have to go to Telegram to find certain extremist content. Now, I can find it quite easily on X—sometimes even amplified directly by Elon Musk himself.

For example, the South African “white genocide” narrative has resurfaced recently. That was a controversial talking point during Trump 1.0, but today, it is not controversial.

Why? Because the Overton Window has shifted, and there is no significant opposition to it. So yes, your question speaks to a larger issue—the question of information consumption.

Where do people get their information?

One of the educators’ main objectives is teaching media literacy. Education should never be about promoting a left-wing, right-wing, or centrist agenda—it should be about teaching people how to critically evaluate sources and information. It should be centered on critical thinking, allowing people to apply it in whatever way they choose.

One way to foster critical thinking is to encourage students to evaluate their news sources and ensure that their media diet is not one-sided.

For example, I always tell my students: I read The New York Times, but I also read The Wall Street Journal. Use platforms like Tangle or similar aggregators that present what the left and the right are saying about a given issue.

I have contributed to The Conversation in some of my more recent public-facing writing. This academic platform makes research accessible.

I also make an effort to explain the perspectives of the MAGA world to people on the left, who often do not fully understand it and tend to reduce it to a simple narrative of fascist authoritarianism. Ironically, in the MAGAverse, many people mirror this perspective—except they believe there is an impending takeover by authoritarian Marxists.

Both sides are locked into these narratives. This kind of binary thinking happens all the time. Each side sees itself as resisting authoritarianism and gravitates toward easy explanations.

This division is particularly evident when comparing platforms: Bluesky vs. X (Twitter)—two completely different realities. Many groups use Telegram, but it is frequently associated with fringe ideologies. Truth Social—a political echo chamber.

We are increasingly living in bubbles.

For educators, the key challenge is teaching students not to take everything at face value: just because you see something on TikTok, it does not mean it is the news. Do not immediately retweet something without questioning it. Always be critical, think twice, and examine different perspectives.

Because, in reality, things are never as simple as one-line answers make them seem.

This ties back to an earlier point about how the left often characterizes the MAGA world as racist—just as MAGA supporters frequently label the left as radical Marxists.

Both of these are caricatures—stereotypes that obscure reality. It is easy to define the other side with a one-word smear. Taking a deep dive, analyzing the issues critically, and engaging with nuance is much harder.

That kind of deep thinking is challenging for many people. Now, that is not to say the words racist or Marxist should never be used. However, people should apply critical thinking when using them.

One final point—when people use words like racist or hater, they individualize the issue. This shifts attention away from the larger historical and systemic problems. For example: saying “structural racism” focuses on systems and institutions. Saying “a racist” focuses on an individual’s character.

However, individuals are raised within these larger social structures, and people need to think critically about this. This applies to both sides because it is part of how human beings understand the world.

The philosopher Theodor Adorno, a member of the Frankfurt School, described this as reification—or “thingification.” This is when we reduce complex social realities to fixed, simplistic categories.

The goal of critical thinking is to resist this tendency, unpack complexity, and move beyond surface-level labels.

Jacobsen: How do white nationalism and other far-right movements in the United States and Europe compare with parallel extremist ideologies—Islamist militancy, Hindu ethnonationalism, and beyond? Where do their logics overlap—in recruitment, grievance, mythmaking—and where do they distinctly diverge?

Hinton: Yes. So, you are asking an anthropologist—which makes this a tricky question.

Anthropologists emphasize the importance of understanding historical and cultural contexts in depth. Because of that, I do not want to dive too deeply into contexts outside my expertise; I will stick to the ones I know best.

That said, I study these movements comparatively and examine their larger macro-dynamics. There are many continuities between them.

For example, the “replacement” discourse we discussed earlier does not exist solely in the United States and Europe. It also manifests in India.

The notion that an external or internal group is “invading” and threatening to take over is widespread. This fear-based formula appears in many societies.

Recently, I was re-reading for my classes about Hermann Göring and Joseph Goebbels, among other Nazi leaders. While imprisoned, Göring was interviewed by a psychologist, who asked him about the past and how things had unfolded in Nazi Germany.

Göring’s response was striking: he said that people do not naturally want war. But if you tell them there is an evil enemy—one that is threatening society, contaminating the nation, or destroying its values—Then they will go to war.

This logic is deeply effective and has been used across history.

Of course, it is not the entire story. Still, mobilizing grievance and fear—whether about “outsiders” or even “insiders” who are framed as existential threats—is a universal tactic in extremist movements. One case that is slightly different in South Africa.

The history of colonialism and land ownership creates a unique dynamic. Unlike in replacement narratives, where the fear is about “invaders,” the tension in South Africa is framed differently.

The Black African majority is reclaiming land that was historically taken. The white minority, which still owns significant land, perceives this as an existential threat.

That is where the conflict emerges. It is not about outsiders coming in—instead, the perception is that the existing population is being “targeted” for destruction.

This is why Elon Musk recently tweeted about a rally in South Africa where someone called for action against white landowners.

The reality is that white South Africans still own vast amounts of land. However, the far-right framing of this situation revives the “white genocide” narrative.

This same existential fear—the idea that “they want to destroy us”—exists in many different extremist movements. It is a deeply resonant message for people who feel their identity, culture, or way of life is under siege.

Earlier today, while preparing for my class, I reflected on Göring’s words. His strategy was simple: Make people afraid. Tell them there is an enemy. They will go to war for you.

This pattern repeats across history—and we continue to see it today.

Jacobsen: Thank you so much for the opportunity. It was great to meet you.

Hinton: Yes, great. I hope this discussion was helpful. Thanks for your interest.