Politics

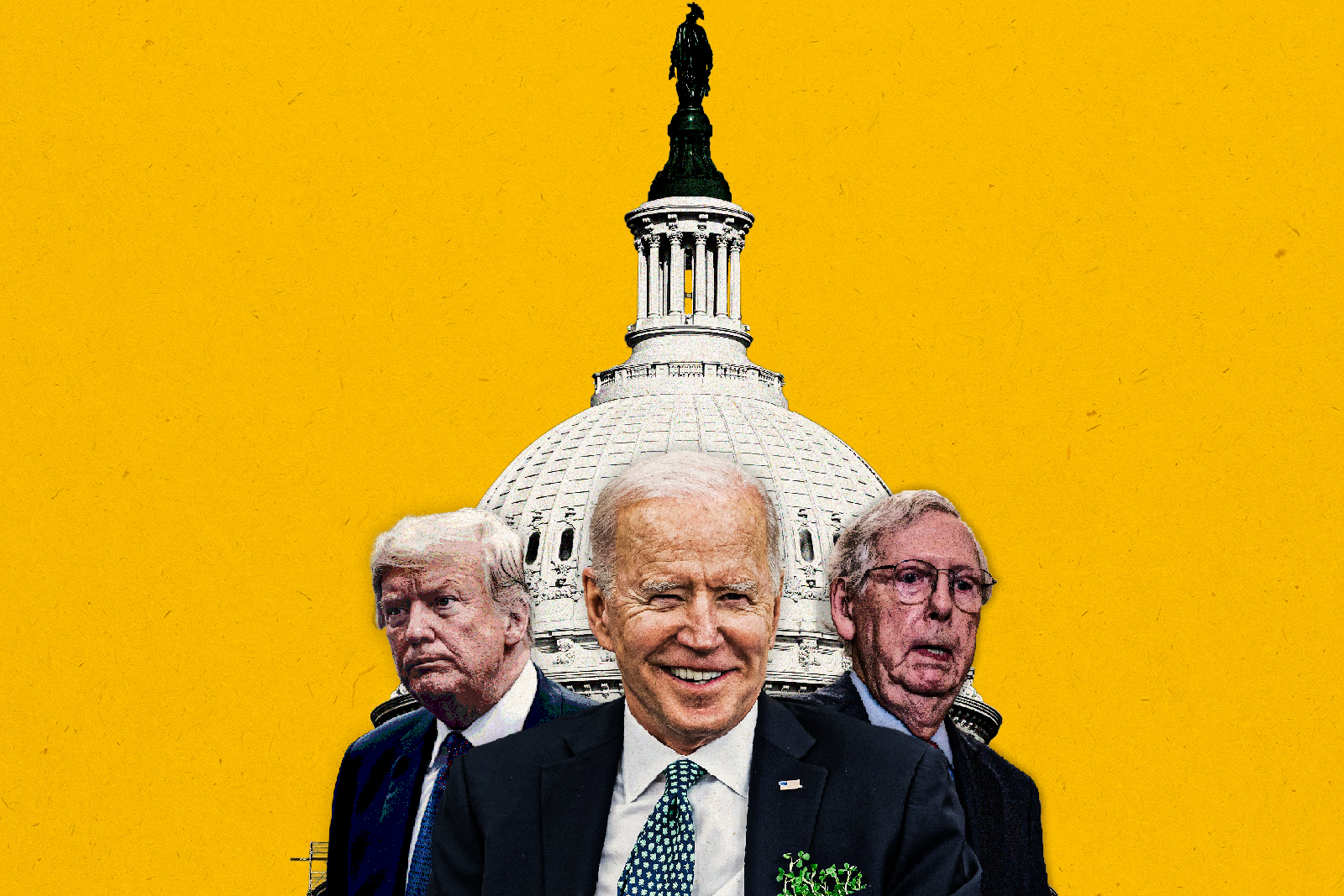

America’s Aging Political Class

The American political system is not exactly a gerontocracy (defined by Merriam-Webster as “rule by elders”), but it has drifted in that direction. Even a casual observer of American politics cannot help but notice that so many major political figures are, well, older. This critique emerged in 2016, when Donald Trump (then age 70) and Hillary Clinton (then 69) constituted the oldest pairing of presidential candidates in U.S. history; only to be outdone in 2020, when 74-year-old Trump took on just-shy-of-78 Joe Biden. If Trump and Biden are on the ballot this November, they will be 78 and (almost) 82, respectively. Recent third-party candidates have trended older as well, including Bernie Sanders (b. 1941), Green Party nominees Jill Stein (b. 1950) and Howie Hawkins (b. 1952), Libertarian Party nominee Gary Johnson (b. 1953), and 2024 dissident contenders Cornel West (b. 1953) and RFK Jr. (b. 1954).

Congress further illustrates the trend. Whereas the median age in the U.S. is 38.9, the median in the Senate and House are 65 and 58. More than one-third of U.S. Senators are at least 70, 56% are at least 65, and nearly 70% are at least 60. It may be fitting that the Senate is so experienced, as the Roman term Senatus was derived from the Latin senex, “old man.” (The same root informs senilis, “of old age.”) As James Madison asserted in 1787, the Senate should be a “necessary fence” of “enlightened citizens” standing against the “fickleness and passion” of conventional horse trading. But just consider how many major figures in the upper house are around twice the national average, e.g., Chuck Grassley (90), Mitch McConnell (81), Ben Cardin (80), Jim Risch (80), Angus King (79), Dick Durbin (79), Elizabeth Warren (74), and Chuck Schumer (73). (Senator Dianne Feinstein was 90 when she passed away this past September.) They are joined by the likes of long-serving House members Maxine Waters (85), Steny Hoyer (84), Nancy Pelosi (83), and Jim Clyburn (83).

It wasn’t always this way. The average member of Congress was in his mid-forties in the nineteenth century, and the congressional median was 51 as recently as the early 1980s. For presidents, the historical median age at first inauguration is 55, and younger presidents held office from 1993 to 2017. Bill Clinton was 46 on inauguration day, George W. Bush was 54, and Barack Obama was 47. Before 2017, Ronald Reagan and Dwight Eisenhower were America’s only two septuagenarian presidents—77 and 70, respectively, when they left office. Between Lincoln and Obama (1861-2017), only three men took the oath of office as sexagenarians: Harry Truman (60), Gerald Ford (61), and George H.W. Bush (66). Even some presidents we think of as old were pretty young, e.g., 42-year-old Theodore Roosevelt and 51-year-old FDR.

While plenty of career politicians and federal judges retire, others find the work—or the perks—hard to give up. Some of America’s most prominent recent politicians have died in office, including Robert Byrd (92), Dianne Feinstein (90), Frank Lautenberg (89), Daniel Inouye (88), Don Young (88), Ruth Bader Ginsburg (87), Alcee Hastings (84), John McCain (days shy of 82), and John Lewis (80). Since Supreme Court justices are appointed for life, many hang on until they can be replaced with an ideologically comparable figure. Sometimes this waiting game works out, as when Biden nominated Ketanji Brown Jackson to replace the Clinton appointee Stephen Breyer. But since Ginsburg passed away during Trump’s tenure, he replaced her with Amy Coney Barrett.

What explains these trends? The simplest answer is that Americans are living longer, officeholders included. Life expectancy at birth has increased for well over a century, rising from 47.3 years in 1900 to 54.1 in 1920 to 78.8 by 2019. The median age has risen from 28.1 in 1970 to 38.9 today. Someone who is 65 today is at even odds to live about twenty more years.

System incentives, too, favor an older cohort. There are minimum age requirements for president (35), senator (30), and congressman (25), but no maximum age or term limit for any elected or appointed federal position besides the two-term limit on presidents. The longer one serves in Congress, the more he or she amasses committee seniority, institutional prestige, public name recognition, and—perhaps the ultimate political necessity—the support of deep-pocketed donors. A long-serving legislator can trade on these advantages and promise more spoils for the home district.

A much darker take is that America’s aging political elite symbolizes a system in decline. This harsh vision of political actors as venal insiders—comfortably ensconced and lavishly remunerated yet unable to solve even the most basic problems, thus fostering historic levels of congressional unpopularity—conjures images of erstwhile sclerotic dictatorships whose leaders’ advanced age mirrored the obsolescence of their ideas. As Mikhail Gorbachev recalled of his accession to power in the Soviet Union in the 1980s, “There was a sense, an intuition, that…the very system was dying away; its sluggish senile blood no longer contained any vital juices.”

In the U.S. context, recent health and cognition episodes involving Biden, Trump, McConnell, and others have brought the age factor to the fore. Age may not be an accurate predictor of health, but advanced age is a risk factor for many afflictions, and a president or senator’s health and cognitive abilities can influence performance in such a demanding, high-pressure job.

How much does age matter to voters? Americans have supported term limits for decades, and we now see a burgeoning interest in age limits. In one recent poll, 79% favored such limits for elected federal officials, and about half preferred a president in his/her fifties. In another, 53% agreed that the job of president is “too demanding for someone over the age of 75,” while only 9% disagreed. When older, more conservative candidates have run against younger, more liberal ones, younger voters have predictably backed the latter. This was particularly true in 2008 when a 25-year gap separated Barack Obama from John McCain; in 1996, when 23 years separated Bill Clinton and Bob Dole; and in 2012, when 14 years separated Obama and Mitt Romney.

But a candidate’s age is only one variable, and rarely the deciding one. After all, plenty of younger officeholders are incompetent, ineffective, or even corrupt, and it is the voters themselves who keep returning senior lawmakers to Washington. These established figures are not only influential, but they may also offer a comforting level of familiarity to constituents. While younger candidates can trade on their youthful energy and the promise of “new” ideas, older candidates can tout their wisdom and accomplishments.

Indeed, some of the world’s greatest leaders have served into old age. British prime ministers William Ewart Gladstone and Winston Churchill served until they were 84 and 80, respectively. Deng Xiaoping transformed China into a modern economic power while in his 70s and 80s. And Singaporean statesman Li Kuan Yew continued to serve effectively in parliament until his death at age 91. In the U.S., younger voters have backed older iconoclasts, such as Ralph Nader in 2000, Ron Paul in 2012, and Bernie Sanders in 2016. For these and other reasons, some call age and term limits undemocratic for denying a candidate’s right to run and a voter’s right to choose.

Today’s conditions are not permanent. Although institutional factors will continue to favor older, established legislators, it is worth noting that the average age in Congress has fluctuated widely since 1789, including a significant drop in the 1970s and ’80s. The tilt toward a slightly younger House in 2023-24 may be a harbinger of things to come. Both parties have ambitious rising stars—Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (34), Jon Ossoff (36), Vivek Ramaswamy (38), and J.D. Vance (39) among them—and it is always possible that a younger and relatively unknown candidate may capture the electoral zeitgeist in 2024 or 2028, much as Jimmy Carter did in 1976, Bill Clinton did in 1992, and Barack Obama did in 2008.