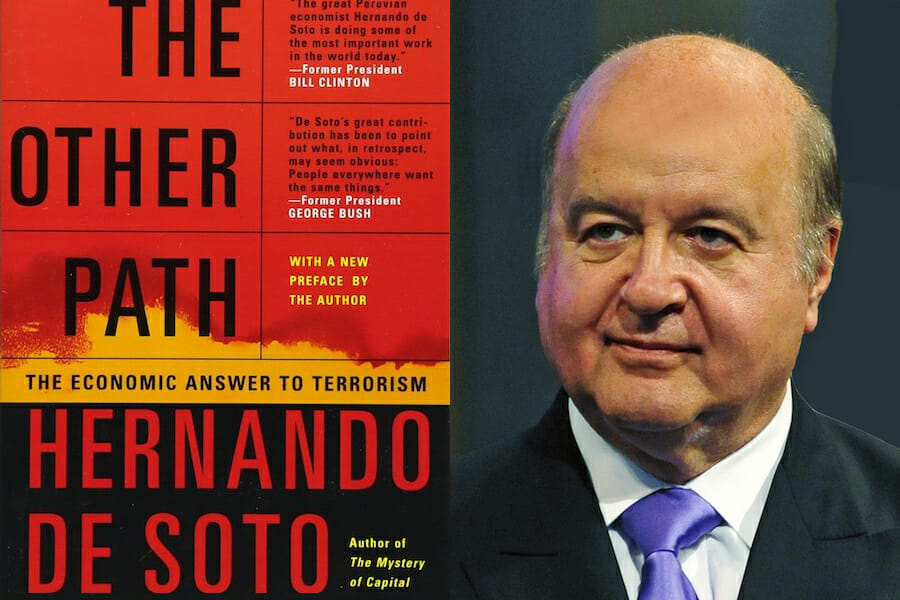

Books

An Economic Answer to Terrorism: Re-Visiting De Soto’s ‘The Other Path’

After nearly two decades in print, the fundamental pillars of Peruvian economist and ex-political adviser Hernando de Soto’s bestseller, The Other Path, continues to resonate with modern economic security affairs. His argument that over-bearing bureaucracy hinders developing economies’ successes are channeled through 1980’s Peru case studies that offer a further comparative perspective to modern crises. However, De Soto stood at a cross roads during his political career that also puts the clarity of his arguments at risk. While he worked to reform such regulations, he also worked for those behind them.

“Simplification means using techniques already well known as ‘de-bureaucratization’ in developed countries,” De Soto states. “These include replacing rules which specify how to fulfill certain requirements by rules stating the ends to be achieved. This would lighten the burden on those who must obey the laws in question, because instead of having to meet certain requirements before they can do something, they will instead be monitored afterward to see whether they are complying with the law. Such procedures, which emphasize ex post de facto monitoring rather than prior paperwork, reduce red tape without abandoning necessary controls but also provide more efficient means of enforcement.”

Despite a multi-partisan past, De Soto’s analysis led many to argue that his work does support a logical argument. One point includes his stated economic beliefs and the strong relationship of trust envisioned as being beneficial amid legal and illegal influences. This is particularly the case in the areas of minimal property rights, underground economies and general lack of security – elements that many developing world citizens experience -are involved

No Re-Inventing the Wheel

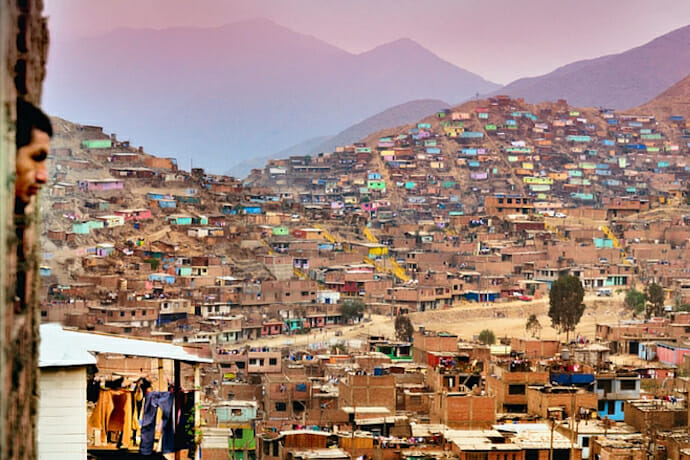

First, De Soto encourages developing countries not to re-invent the wheel regarding economic elevation, but to look toward their second and first world counterparts. As a political adviser in Fujimori-era Peru and head of his organization, the Institute for Liberty and Democracy, De Soto witnessed firsthand the tribulations of developing countries attempting to correct impoverished and insecure circumstances via overt regulation. Peruvians were experiencing daily constraints, such as “house but not titles; crops but not deeds; businesses but not statues of incorporation.” The government was having trouble regulating unofficial endeavors, and the common man was having trouble progressing in the face of rigid official bureaucratic walls.

Overall, problems were out of hand, so why not support a tighter grip? While De Soto could have supported additional regulation, he countered this trend, explaining that that method proves counterproductive. When society’s poor cannot turn to official authorities for permission to grow – for example, through residential development or small businesses – due to bureaucracy, they occasionally turn toward illegal authorities. In dealing with the Shining Path, De Soto identified terrorist groups’ strategy in economically enabling faster growth when government red tape would not. This is costly in the big picture, as the ironic increase of law also fed the increase of criminal organizations.

Therefore, De Soto concludes that by “simplifying” bureaucracy, lessening “certain requirements” and permitting individuals to grow under a broader umbrella of “complying with the law,” developing societies are permitted to prosper more fluidly and yet still legitimately. He was able to identify the big picture benefit of the populations multiple socio-economic classes, even if at the small picture risk of loosening governmental grip.

Valuing Alternatives

Second, while De Soto acknowledges the necessary value of government regulation and openly elaborates upon evidence of it, he additionally presents testimonies from other involved parties. This includes different classes and entities such as terrorists. He does not merely accept authority’s claims, but considers alternative interpretations about history and certain lessons relevant to the present day.

In the previously cited paragraph, he also refers to particular “necessary controls” regarding public sector supervision and regulation of informal economic activities. De Soto fully supports government involvement in local development, despite calls to loosen it in certain areas. How such dilemmas don’t weaken his stance relies on balance. Being part – and employed – by privileges and sympathizing with those less privileged actually earned De Soto a valuable place in handling Peru’s quagmires.

Despite officialist perspectives, he includes additional testimony that grass roots development requires space to occur. For example, many slums originate illegally, but throughout The Other Path, De Soto argues that if many of those slums are allowed to be so, they then can become more established and care for their more permanent inhabitants and some go on to become middle class neighborhoods. This relates to his position that “replacing rules which specify how to fulfill certain requirements by rules stating the ends to be achieved.”

Free Market

Third, De Soto keeps informative and analytical expose to a succinct flow. The book adheres to this rule by logically presenting a claim, that too much red tape can do more harm than good to developing societies. Crime and inequality can become one hefty price to pay. He proceeds to the body of argument and logical evidence that society benefits more when requirements are second to overarching compliance with the law. New housing projects are a major theme.

Lastly, he recapitulates, stating that red tape does not mean no tape, but liberty for all levels of society to grow and thus benefit all. This goes to show that the free market, not to be confused with mercantilism, does not chase away productive citizens as socialism does, but encourages big picture productivity.

Yet again, entertaining multiple perspectives proved its worth. De Soto’s professional economic and political past in his country over the course of decades helps make the logical arguments he offers even more tangible.

21st Century Resonations

The Other Path not only communicates what De Soto has learned firsthand as a participant, analyst and bystander of the late 20th century and early 21st century affairs, but as one honoring non-faulty logical arguments. Despite the need of some controls, “de-bureaucratization” ultimately permits those of the lower classes to advance, while meanwhile maintaining authority among government and corporations.

More specifically, it gives a chance to bring millions from informal economies to legitimate ones. Legal authority must monitor public activities due to the historically proven reality that illegal entities take over in their absence. Balance is key, and comprehending how to manage it from a broad perspective is even more key.

Therefore, the historical case studies and logical lessons De Soto implements in The Other Path may provide the economic answer and a strong case for combating terrorism.