Culture

Assessing the Complicated Legacy of Mustafa Shokay

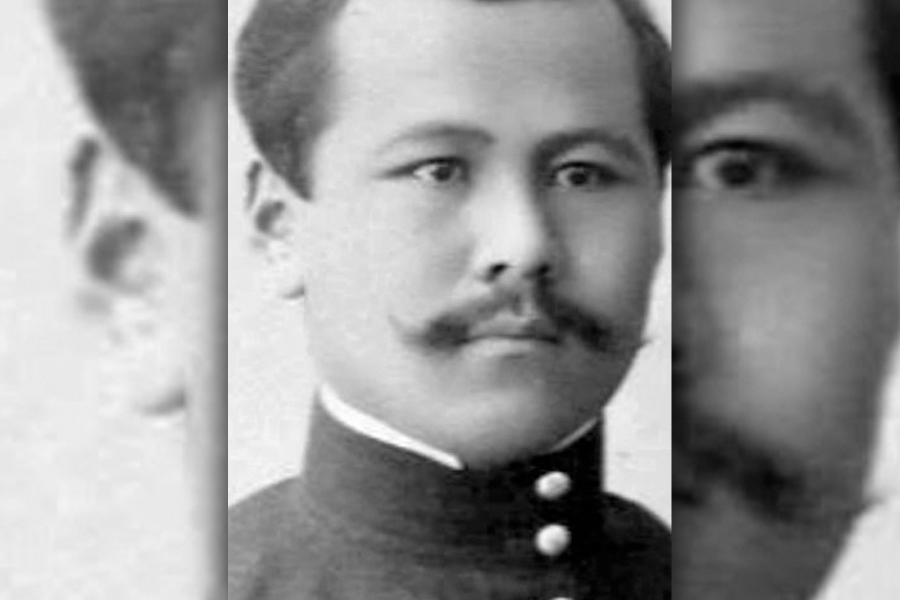

It is impossible to overstate the power of propaganda throughout the Second World War and the Cold War. Along with creating national narratives and heroes, propaganda machines churned out demons by the thousands. One such individual whose legacy has been tarnished is Kazakhstani activist and scholar Mustafa Shokay.

Captured by the Germans when they entered France, Shokay’s time in Nazi captivity has been a subject of both fact-based speculation and wild conspiracy theories. During the Soviet era, he was branded an accomplice of Nazi Germany; however, the dissolution of the Soviet Union allowed new studies of his life, showing a complex and multifaceted individual devoted to an independent homeland for his fellow Turkic people.

Separating fact from myth

Shokay, a politician, publicist, scholar, and human rights activist, was born in 1890 in modern-day Kazakhstan, and later received his higher education in Russia. One of his passions was helping the Turkic people, including the people of Turkestan, become an independent nation. According to the Alash Orda Project, he “was appointed a secretary of the Muslim faction of the State Duma of Russia on the recommendation of [Alikhan] Bokeikhanov in 1916.” The Alash Orda Project adds that during his time there, Shokay worked “in the Committee of the State Duma [where] he investigated the causes of the national liberation uprising in Turkestan [and] engaged in the return of the Kazakhs mobilized to the front.”

According to Dr. Akerke Zholmakhanova, a professor of literature and language at Korkyt Ata University, Shokay’s passion for his fellow Turkic people led him to become first an activist, then an editor, and publicist for several journals, newspapers, and magazines in Turkic-speaking and Muslim areas. As Zholmakhanova notes, Shokay’s most valuable legacy comes from 1917 Жыл Туралы Естеліктерден Узінділер, or Excerpts From Memories of the Year 1917. Upon returning to Turkestan in 1917, Shokay “took an active part in Shura-Islami [the Islamic Council], because this organization supported the policy of the provisional government on the development of Turkestan by democratic means; it also fought for the rights of the local population,” as Zholmakhanova explains.

As the Russian civil war continued and Bolshevik control spread to Central Asia, Shokay migrated to Western Europe, but his goal of creating a united and independent Turkestan for Turkic people never subsided. Shokay was eventually arrested in Paris after the German army arrived in 1940. There is a dispute over whether he was murdered, or died from an illness contracted in a concentration camp.

Much like the cause of his death, Shokay’s life after capture has become the subject of controversy. According to some accounts, Shokay, at the time a French citizen, was detained and sent to Château de Compiègne, along with other prisoners. Shokay reportedly felt at peace at the château; in one letter he wrote to his wife, Maria Gorina-Shokay, “I met very interesting people, both Russians, and foreigners…I felt rejuvenated there, I remembered my student years, lectures, gatherings in St. Petersburg. In Compiègne, wonderful lectures, political disputes were held in the open air.”

It is unclear to what extent Shokay believed Hitler’s ideals and objectives. It is understood that he reportedly offered to help create and train a unit of Turkic soldiers, who would fight for Berlin in order to defeat the Red Army. But when Shokay was made part of a special commission that visited prisoner of war camps where Red Army soldiers were being held, he quickly comprehended the terrible reality of what Nazi Germany stood for. This is where the situation becomes complicated.

Shokay was deeply anti-Bolshevik and anti-Soviet, and his tacit support for his captors was a method to achieve the ultimate goal of defeating Moscow if this meant that his Turkic compatriots would be free and independent. The Kazakhstani probably quickly realized how wrong he was after learning more of what the Nazis were doing across Europe—and it is worth remembering that the Nazis were able to keep the camps a relative secret until much later in the war. Upon his exposure to the truth, Shokay ultimately decided that, while he could not take up arms to resist the Nazis, he would not help them. “I cannot accept the offer…to lead the Turkestan Legion and refuse further cooperation. I am aware of all the consequences of my decision,” he reportedly wrote in a letter.

The Turkestan Legion was created in 1941, as the Wehrmacht could not successfully fight several fronts simultaneously while defeating the Red Army proved more difficult than anticipated. The Legion was mobilized by 1942 and fought in Western Europe and Yugoslavia. After the war, many former members of the Legion were punished for collaborating with the Nazis.

Shokay did not live to see the end of the war, or even to see the Legion in action. Whatever the cause, he passed away in December of 1941.

Shokay’s name survived long after his death. The Nazi propaganda machine mentioned him as an example of how prominent Turkic individuals supported their cause and objectives. Predictably, the Soviets described him as a traitor and a fascist accomplice–see for example The Fall of Turkestan written in 1972 by Serik Shakibaev. Shokay is depicted as the main ideologist and standard-bearer of the Turkestan Legion; however, the book also erroneously claims that Shokay survived until the Spring of 1942. One theory is that the book was written with this date so that Shokay could be accused of being an active member of the Legion, rather than passing away before it was mobilized.

Remembering Shokay today

For a long time, Mustafa Shokay’s name was not well-known in Central Asia. This is not surprising, as Zholmakhanova explains that “until the period of independence acquisition the history of Kazakhstan was considered only in the history of the USSR, which was a consequence of the colonial policy of [Imperial] Russia.” Due to that way of thinking, and the Soviet propaganda machine ensuring that only state-approved history was taught in schools it is easy to understand why Shokay’s name and legacy were either forgotten or distorted.

Soviet censorship of education and thought ended in the 1990s, with the collapse of the Soviet Union. Afterward, it became customary in many former Soviet Republics to praise local individuals who fought against Bolshevism, including individuals who sometimes had to make morally questionable decisions. In the Baltic, the “Forest Brothers” became heroes, while the legacy of Red Army General Andrei Vlasov has been revisited.

How Shokay is remembered has similarly changed in recent years. The times in which he lived are better understood now, as are his actions. Now we know that upon his arrest, Shokay visited concentration camps, wrote several personal letters, refused to collaborate in the creation of the Turkestan Legion, and ultimately passed away in a hospital under suspicious circumstances.

In Kazakhstan, Shokay’s homeland, streets are named after him, and monuments are erected to remember the good he did. Kazakhstani schools and universities study his legacy as well. For Kazakhstan and many Turkic people, he was an educated scholar and an activist that wanted freedom for his people. The actions he carried out while under Nazi control were those of a person trying to survive a genocidal regime, not those of a willing collaborator.

***

Kazakhstan has come a long way since Mustafa Shokay’s time. The country is regarded as the powerhouse of Central Asia and aims to become one of the 30 most developed nations by 2050. Nur-Sultan has close and cordial relations with both Moscow and Berlin. Russian-Kazakhstani trade and defense ties remain strong. As for ties with Germany, in an op-ed written for Diplomat Magazine, Dauren Karipov, Kazakhstan’s ambassador to Germany, explained how “in the past 13 years, direct investments amounting to more than $8.6 billion have flowed from Germany to Kazakhstan.”

The Second World War occurred over seventy-five years ago, but the world is still studying and learning from this conflict, including understanding the roles that people around the globe played. Shokay could have never predicted that his decision to migrate to Europe as part of his own personal quest to help his fellow Turkic people would put him on the front lines of one of the worst chapters of human history.

Mustafa Shokay is one of those individuals that the West does not know much about, but whose name has been manipulated long after his death. He was a journalist, politician, and activist; he was anti-Bolshevik, but not pro-Nazi Germany. Further research is necessary to understand who he really was. Even thirty years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, disinformation, and propaganda remain powerful tools for shaping international narratives, but hopefully one day we can all understand better Shokay and remember him appropriately.