Australia’s Impending Minsky Moment

The Australian media’s obsession with housing is starting to give me real estate fatigue, but a recent catch phrase ignited my curiosity. A term being thrown around the financial industry recently has been of “soft landing” for the housing market. This idea of a housing correction being smooth, without chaos from households tightening the purse strings and giving the finger to the GFC is pretty damn intriguing. Is it possible that the Australian regulators APRA (Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority) have created an example the rest of the world could follow?

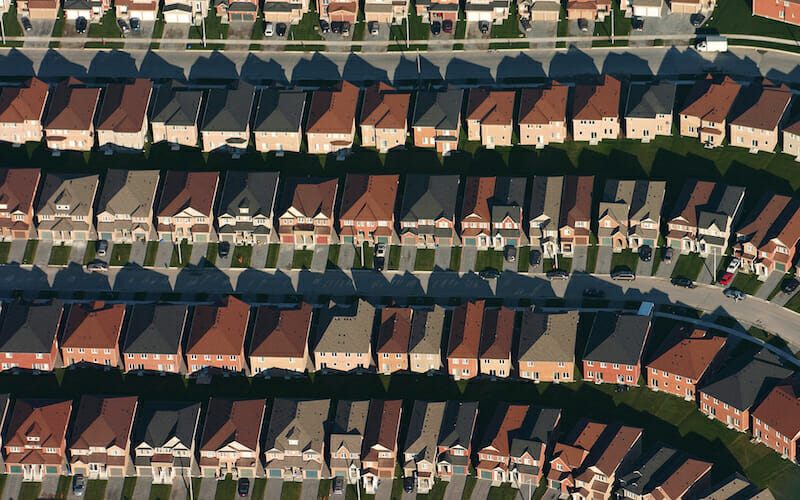

As house prices skyrocketed, investors made up the bulk of the property buyers; first-time homebuyers were quickly becoming relics of the past. Rather than following monetary policy and tightening rates to cool the housing market, the regulators stepped in with a targeted approach. APRA put pressure on the banks for investor borrowing. Since then, investor numbers have receded and first-time borrowers have made a resurgence. Property prices are mostly falling and/or stagnating (depending where you are), but the market correction appears very gentle.

The controls on credit and credit criteria really led me to question the role of monetary policy and interest rates. What if access to credit is as or more important than the price of credit? The Australian banks and regulators are clearly demonstrating how restricting access to credit can influence markets.

The Forgotten Economist

Tucked away in the dry and humourless economics books is one of the most pertinent economists. Household names like Keynes, Friedman or Adam Smith have theories that are widely used, applauded, criticised and they have all failed at some point or another. An economist who received a brief renaissance amongst a small community of economists after the GFC is Hyman Minsky, and he may have the keys to the kingdom as his theories are all about credit, and financial instability.

With our banking systems ballooning over the past century and the fractional banking system pouring out money, it only makes sense to review the role and nature of credit and finance. These theories become increasingly relevant, given the extreme indebtedness of the Australian people from their home-buying frenzy.

There’s a large amount of simple logic behind Minsky’s thoughts. During prolonged periods of economic growth, banks and market participants obtain ever-riskier assets which creates systemic risks. In plain English, this means that as growth motors along, we build increasingly greedy expectations of returns and margins for risk. The stronger and healthier the economy looks, the more confident we become and the more investment risks we take. “There’s no way that over-indebted business will collapse because the broad economic growth is the tide that lifts all boats.” Well of course, that isn’t the case. More important is the function of the access to credit and the drivers are returns for banking stocks.

Let’s start with the banks. Banking stocks make a large portion of their revenue from writing loans, and, like any market, the number of people who are able to “buy” a loan and want to “buy” a loan is limited. As the economy grows and grows, the market for loans begins to converge and there are less and less people who are both able to buy and want to. Pressure is applied to maintain returns for the shareholders and to stay in line with the broad economic growth.

Thus, the banks chase returns for their shareholders with risky loans. After all, those previously risky loans, aren’t risky anymore. The bank relaxes its credit criteria and allows for more people to borrow. This increases its customer base, increases or maintains shareholder returns and continues to show how healthy and robust the economy is.

It’s this process of relaxing credit criteria or access to credit that is the beginning of the end. It’s this process that created NINJA loans “no income, no job and no assets” and according to a recent survey by UBS, $500 billion of “liar loans,” or mortgages obtained on inaccurate information or soft fraud. Remember, a hallmark of the Great Depression was in the number of fraudulent loans.

This creates more growth. House prices increase, household & sovereign debt climbs and eventually it’s all so highly leveraged that only a small increase in bad loans or a similar negative event has a snowball effect.

The Asset Downswing Cycle

Soon after this point, we start to see asset prices fall. This is then followed by increases in non-performing loans. Profits fall…confidence falls. Historically a collapse in confidence is followed by a systemic credit crunch. Banks have lost faith in people’s and even other banks ability to repay. They stop lending, credit access gets restricted, and the system grinds to a painful halt. What’s interesting to note here, is that the normally low-risk loans are now perceived to be high-risk.

What is fascinating in Australia is that the regulators have induced the asset downswing cycle without using broad interest rates. Regulation around lending criteria, responsible lending and targeted increases in interest rates have been utilized to control the market and smooth the economic cycle.

Regulators are restricting credit access and not the cost of credit to cool an overheated market and create that “soft landing.” This tactic has meant that shareholders have reduced returns into banking shares prior to a collapse of asset prices and a rise in non-performing loans. The bad news has been factored in already. The unknown factors in Australia’s economic mix are still non-performing loans and overall indebtedness. Not only are households addicted to debt, but the government can’t seem to manage its money either.

The risk of this high debt is exacerbated by a lack of wage growth. Traditionally we could pin the tail on the donkey that is wage growth to ease the burden of high debt commitments. Households would be earning more year-on-year and their debt commitment would become a smaller and smaller percentage of their income. Instead, what is happening is the average loan size is continuing to rise faster than both wages and inflation.

On the non-performing loans front, there is mixed news. Loans more than a month overdue rose to 1.54% for the September quarter last year, up from 1.48% a year ago. However, in the last quarter of 2017, delinquency rates actually fell. Aussies got marginally better at repaying debts on their houses.

Throwing another curveball is the current housing supply. When everyone expected new housing approvals to go into reverse; they instead soared by 11.7% last month. Behind the numbers though, is the fact that nearly all of this increase was concentrated in Melbourne apartments, which is hardly surprising given the city’s population growth.

So have Australian regulators bucked the trend?

Well that’s impossible to answer without a crystal ball. Minsky may have another moment, another demonstration of the roles and risks of credit and financial stability. If anything, this situation demonstrates that betting against the Australian economy may not be a bad thing, what with 26 going on 27 years of economic growth with inept politicians, heavily indebted households and governments and high asset prices…The economy is on the precipice and it’s impossible to tell if there’s a parachute or not. All I can see is that there are great opportunities abroad and there are significant risks in the sunburnt country.