Back on the ‘Stairway to Heaven’: Led Zeppelin Wins Over Spirit

In March, the 9th US Circuit Court of Appeals upheld an original jury finding that Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” did not infringe copyright on Spirit’s 1968 song “Taurus”. Michael Skidmore, who had filed the suit in 2014 as trustee of the estate of the late Spirit guitarist Randy Wolfe, was hoping that the US Supreme Court would take time to hear, and hopefully reverse the decision. The highest court in the US refused to bite.

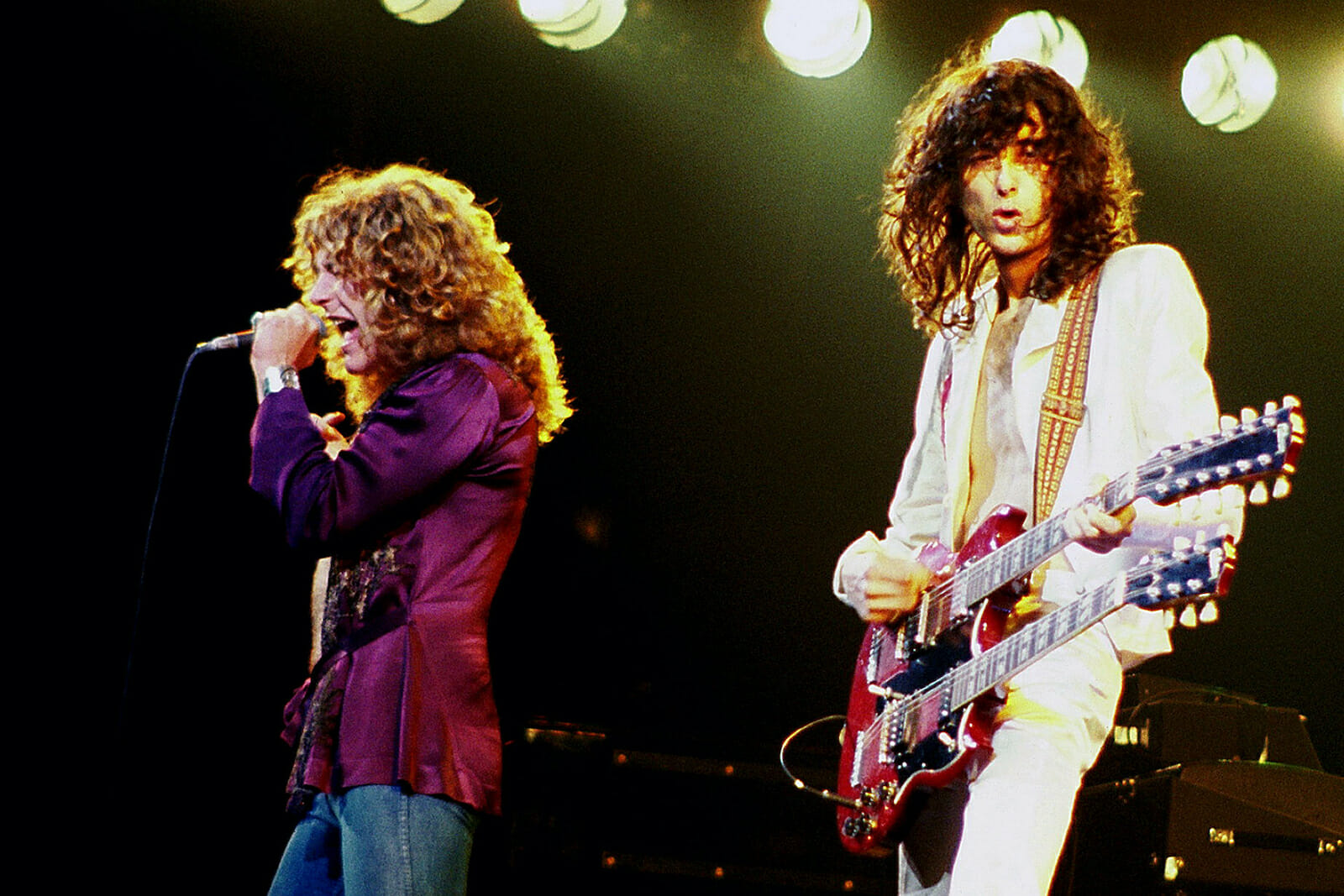

Wolfe, known professionally as Randy California, wrote “Taurus” sometime between 1966 and 1967. On composing the song, Wolfe’s publisher armoured “Taurus” with copyright protection as an unpublished work, though such protection was superficial chainmail rather than full breast plating. “Stairway to Heaven,” the durable, seemingly ageless fruit of Jimmy Page and Robert Plant, was released in 1974 on Led Zeppelin’s fourth album. That particular song has caused spasms of delight and swooning, along with much reverential acknowledgment in guitar land over the years. But it has also given much carrion to the legal eagles. It was a sign that music, as with much else intellectual and even spiritually motivated, could be the subject of a battle to match other lengthy human conflicts.

The jury in the original district court trial found in special interrogatories that the trust owned “Taurus,” and that Led Zeppelin had access to it. This did not lead them to conclude that the songs were substantially similar. Led Zeppelin had argued that any similarities between the songs were for those elements not protected by copyright law; the plaintiffs argued that the “selection and arrangement” of those elements was.

The outcome at first instance did not deter Skidmore, who took the case to a three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit. Initially, success. The decision was vacated in September 2018 and a new trial ordered. Both parties then petitioned for a review of the decision by all the judges of the Ninth Circuit. This highly unusual request was granted, with an en banc rehearing taking place on September 23, 2019.

The decision to revisit the case was not universally condemned, though reversing jury verdicts tends to cause more than raised eyebrows. For one, it resembled, in reverse, the outcome of the Blurred Lines case, where the jury’s flawed conclusion was not deemed worthy of adjustment by the Ninth Circuit. Copyright lawyer Rick Sanders, writing for Techdirt, noted the “unhelpful legal framework for determining copyright infringement” that had marked the original ruling on “Taurus”.

That framework included an awkward creature of law known as the “inverse ratio rule,” which holds that the greater the similarity between two works, the less proof of access is needed. Embraced by the Ninth Circuit in 1977, the rule can also be put this way: “the stronger the evidence of access, the less compelling the similarities between the two works need be in order to give rise to an inference of copying.”

How it is applied is critical. The “bad framework,” as Sanders suggests, involves proving that the defendant has access to the copyrighted work and “substantial similarity” between those works. The preferable framework is one where the plaintiff must prove “copying” and “unlawful appropriation.” To prove the former, access and “probative similarity” must be shown. Unlawful appropriation amounts to substantial similarity, but probative similarity comes closer to an accurate yardstick than that of “substantial similarity.”

The original district court decision could also be said to be defective on the issue of the jury instructions. This was less a case of misdirection than no direction at all, rendering it incomplete and sloppy. What was the jury to make, for instance, of how to approach “works made up of unprotectable elements”? The issue was never put by the judge.

The en banc ruling restored the original district court’s decision favouring Led Zeppelin. Significant was the less than ceremonious burying of the inverse ratio rule. It thrilled lawyers of copyright law, as well as it might have. Brian Murphy was delighted that attorneys specialising in the field were finally provided with “greater clarity…about the standards for providing copyright infringement.”

The full complement of judges, in training their daggers upon the inverse ratio rule, noted the “confusion about when to apply the rule and the amount of access and similarity needed to invoke it.” They noted how dealing with the rule had been a struggle, mocked and rejected in the Second Circuit as early as 1961 for being a “superficially attractive apophthegm which upon examination confuses more than it clarifies.” It was illogical, even nonsensical. It did not follow that more access “increases the likelihood of copying.”

The judges also noted that the very concept of access had been “increasingly diluted in our digitally interconnected world. Access is often proved by the wide dissemination of the copyrighted work.” The very “ubiquity of the ways to access media online, from YouTube to subscription services like Netflix and Spotify, access may be established by a trivial showing that the world is available on demand.” The inverse ratio rule unfairly advantaged “those whose work is most accessible by lowering the standard of proof for similarity.”

The slaying of the rule did not mean that “access cannot serve as circumstantial evidence of actual copying in all cases.” Evidence of access and probative similarity were still elements to prove in instances of actual copying.

The en banc court also held that the scope of copyright protection for an unpublished work lies in the deposit copy filed with the Copyright Office that forms the copyright application. The dry wording of Section 11 of the Copyright Act of 1909 states that copyright for an unpublished work is obtained “by the deposit, with claim of copyright, of one complete copy of such work if it be a…musical composition.” “The purpose of the deposit,” and the fact of the work’s completeness, served to give, the judges claimed, “notice to third parties, and prevent confusion about the scope of the copyright.”

Central to this was a specific idiosyncrasy adopted by the Copyright Office. Sheet music, not sound recordings, were accepted as deposit copies. Somewhat barer, thinner things, such sheets often constitute skeletal matter yet to receive flesh. When “Taurus” was registered, the Copyright Office had in place a practice for applications registering unpublished musical compositions by “writ[ing] to the applicant pointing out that protection extends only to the material actually deposited, and suggesting that in his own interest he develop his manuscript to supply the missing element.”

The consequence of this was significant and, from Skidmore’s perspective, gloomily decisive. The eight-measure passage commencing the deposit copy of “Taurus” allegedly infringed by Led Zeppelin is a less fed, extravagant creature than the sound recording released by Spirit. The deposit copy, not the recording, defined the “four corners of the ‘Taurus’ copyright.” The judges accepted that the district court had not erred in declining “Skidmore’s request to play the sound recordings of the ‘Taurus’ performance that contain further embellishments or to admit the recordings on the issue of substantial similarity.”

On receiving the deflating news from the Supreme Court, Skidmore’s legal team was more than bruised. “The ‘Court of Appeals for the Hollywood Circuit’ has finally given Hollywood exactly what it has always wanted: a copyright test which it cannot lose.” Portraying himself as a hero fighting major industry defendants and their predatory instincts, Skidmore is adamant about the consequences. “The proverbial canary in the coal mine has died; it remains to be seen if the miners have noticed.”