The Beginning and End of Press Freedom in Cambodia

The year is 2004. The place is Phnom Penh.

I am interviewing Somaly Mam, a famous anti-human trafficking advocate with a glittering catalogue of benefactors including Hillary Clinton, Angelina Jolie and Queen Sophia of Spain. The day before, Mam had led a rescue of 83 women and girls from an illegal brothel run by a high-ranking military figure – and took them to a women’s shelter. But the very next morning a group of heavily armed men raided the shelter, abducted the women and girls and took them back to the brothel.

Somaly Mam had been threatened and was in fear of her life, with Cambodian police refusing to give her any kind of protection. And there I was, covering a major news event that in coming days would be picked up by veteran journalists like Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times.

But I was not a veteran working for a global newspaper. I was a clueless rookie, a journalism cadet one year out of the University of Technology Sydney’s postgraduate school. Yet instead of following a regular career path – scoring an entry-level role with a suburban or rural newspaper and slowly working my way up to the top – I took a gambit and flew to Phnom Penh for an interview with Bernard Krisher, a former Newsweek Tokyo Bureau Chief turned publisher-philanthropist.

In 1993, on the bequest of Cambodia’s late King Norodom Sihanouk, Kirchner founded the country’s first independent newspaper.

Produced in a moldy hotel room on a threadbare budget by a team of American rookies and local university students, The Cambodia Daily looked more like a school newsletter than a big city daily. But it would prove a game changer in a country emerging from the ashes of the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime and still in the grips of civil war: a pillar of truth and democracy in a land where freedom of expression was an alien concept – a luxury enjoyed by wealthy democracies of the West.

In sync with its motto ‘All the News Without Fear or Favor,’ it exposed high-level corruption, crooked cops, illegal logging, extrajudicial killings, child-sex tourism, gang rape, land grabs, forced village evictions, border skirmishes, prison breaks, fake doctors, dodgy orphanages, human trafficking, drug-dealing monks, pedophilia rings, trigger-happy cops, and acid attacks by jilted lovers on a daily basis.

It became, in short, the country’s first reliable record of history.

A Cambodian member of parliament once told me when he wanted to know what was going on behind the scenes, he would read my newspaper. But as of last week, The Cambodia Daily is no more – and not because its business went kaput. The Daily was never meant to make a profit.

Krisher burned hundreds of thousands of dollars keeping it afloat and used all of its advertising revenue to build schools and hospitals.

Instead, the Daily met its end following legal threats over an AU$7.9 million tax bill concocted by the government to silence its most vocal and intelligent critic. And it coincided with the recent closure of 19 radio stations, including US-backed Voice of America and Radio Free Asia.

“The thief has not paid tax to the government for 10 years,” said Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, a former Khmer Rouge cadre with a glass eye who’s ruled the country with an iron first since usurping power in a 1997 coup.

“If you don’t pay tax to the government, pack up and go,” Hun Sen said, adding, as an afterthought, he had no “political motive.”

Now in the twilight of his life and wheelchair-bound by heart disease, Krisher begged to differ in a stinging riposte penned from his home in Tokyo: “Like most other small newspapers, The Cambodia Daily did not charge VAT until that requirement was enforced in 2016. Every ministry in Cambodia knew about this and approved as they placed and paid for many ads over two and a half decades, including the Ministry of Finance, the General Department of Taxation, the Ministry of Information that approved our media licenses, as well as the police and the army. The charges against my newspaper are the regime’s thuggish attempt to disable our operations in haste.”

More than just another news outlet, The Cambodia Daily was also the country’s first school for independent journalism.

Hundreds of rookies cut their teeth on its antiquated computers – many of whom have gone on to become titans in their fields. My closest friend at the newspaper, Charles McDermid, is now an editor at the New York Times. Kuch Naren, one of Cambodia’s first female reporters and probably its most fearless, is now a correspondent for Al Jazeera in Phnom Penh.

“So many outstanding Cambodian journalists were trained there. I just hope they can carry the torch and the dream of a free Cambodia won’t die,” says Erik Wasson, another old friend from the Daily now working for Bloomberg in Washington D.C. “Getting denounced by Hun Sen on Cambodian television for one of my articles on the economic cost of corruption was the highlight of my reporting career.”

Adds Phorn Bopha, a former Daily reporter and current fellow at the prestigious Hubert H. Humphrey journalism program in the US: “Without the paper. I would not be who I am now.”

But they weren’t all good times at the Daily. My first supervising editor was a mean old bastard who took great pleasure in humiliating me in front of my peers over the slightest infraction.

Another time, I stepped over a senior Cambodian journalist who was napping on the floor in the middle of a hallway. I meant no offence, but he went nuts over what he considered the height of rudeness and we very nearly came to blows.

And while they may have been the engine of the newspaper – getting quotes and statements in a language very few of us could understand – the Cambodian journalists worked in that hallway while we white guys sat in the main room.

And we all had the wool pulled over our eyes by anti-human trafficking advocate Somaly Mam.

In 2014, she was exposed by Newsweek for lying about being a former child sex-worker and the rape of her own daughter in revenge for the brothel raid I helped legendary Cambodian journalist Saing Soenthrith break back in 2004.

But all busy newsrooms have their problems, and ours had no impact on the eagle-eye reportage that filled the Daily’s pages six days a week for 24 years and 15 days.

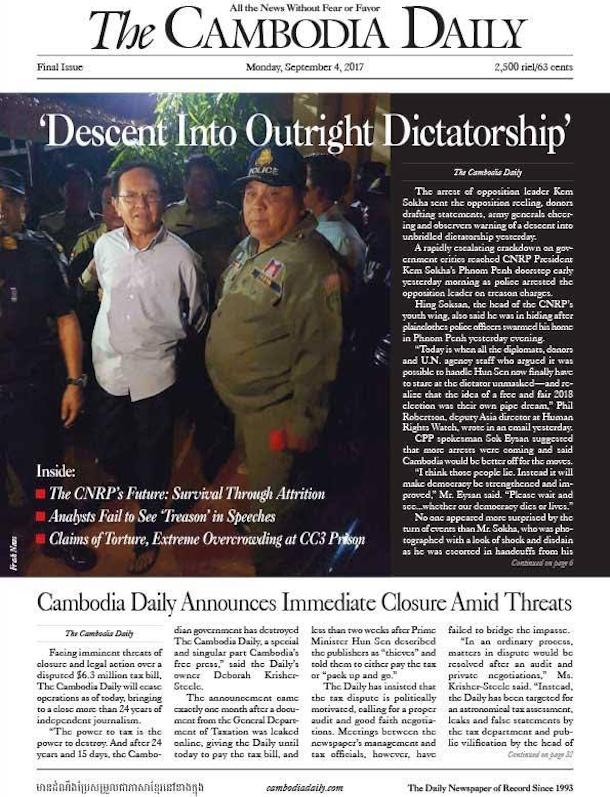

A few weeks ago, as the final edition was about to go to press with the newspaper’s own obituary leading the news, someone in the newsroom got wind of the arrest of opposition leader Kem Sokha on trumped-up treason charges.

The team sprang into action, breaking one last global news story under a shared byline in the 11th hour. The headline ‘Descent into Dictatorship,’ was both fair and spot-on, a fearless ‘up-yours’ to Hun Sen.

I only wish I could’ve been there to offer the team of 65 staff a standing ovation as the Daily was dispatched to the printers for the very last time.

“Take a bow @Cambodiadaily,” tweeted Kevin Doyle, the newspaper’s longest serving editor-in-chief. “You were set up knowing the government would probably shut you down one day for doing your job.”