Books

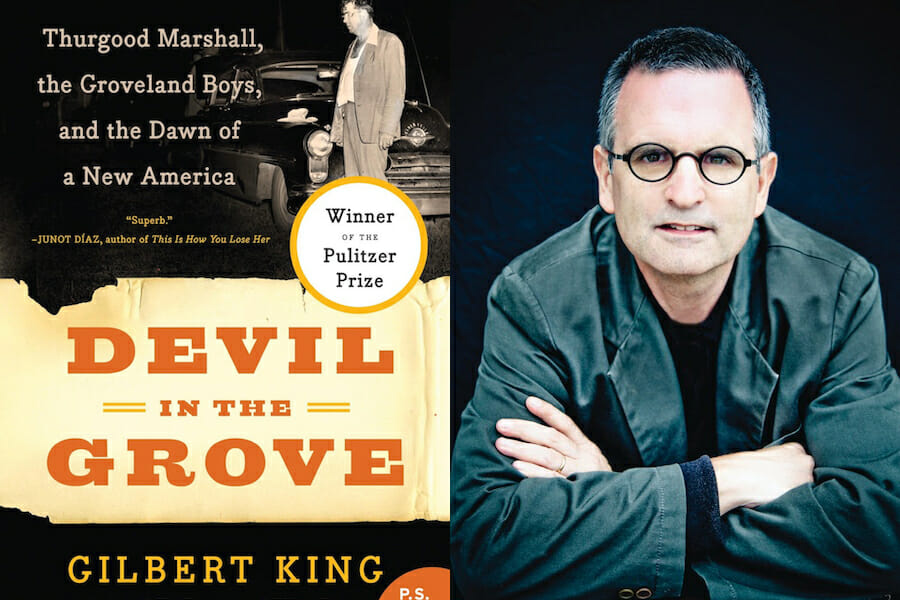

A Book for Black History Month: ‘Devil in the Grove’

Last year featured a strong slate of Hollywood films on anti-black discrimination in America: 12 Years A Slave, Fruitvale Station, Lee Daniels’ The Butler, and 42. Someday soon, theaters will show what will surely be a powerful new entry to this genre; Lionsgate Entertainment has bought the film rights to Gilbert King’s Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America (2012), winner of the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction.

Devil in the Grove narrates the underexposed but dramatic early career of American icon Thurgood Marshall. In the book, the brilliant lawyer and his NAACP colleagues travel to central Florida to defend four black boys from accusations of abduction and rape in the small citrus town of Groveland.

From 1949 to 1955, the defense battles a Southern system of injustice, bigotry, and incompetence. Before the boys are even charged, the scene of the alleged crime—central Florida’s Lake County—erupts in violence and hysteria.

Rioting forces the governor to call in the National Guard. Henry Shepherd, the father of one of the defendants, loses his home to arson. Despite mob gunfire, Lake County Sheriff Willis McCall refuses to make any arrests. The Orlando Morning Sentinel publishes an editorial cartoon of four electric chairs with the title, “No Compromise!” With the Ku Klux Klan gathering, one of the defendants flees Groveland and is killed by a posse. The other three are beaten by law enforcement officials at the county jail.

When the trial finally takes place, the judge spends as much time whittling a piece of wood as he does listening to counsel. He ignores the absence of expert medical testimony on physical evidence of rape. When the U.S. Supreme Court orders a new trial, the state’s attorney exploits his own old age and failing health to appeal to the jury during his closing statement.

Devil in the Grove ably rounds out Marshall’s life story by supplying legal and personal background to his fight to force the “Dawn of a New America.” Before joining the Supreme Court in 1967, Marshall was one of the country’s greatest advocates before its bench. He crisscrossed the country dozens of times a year, a NAACP lawyer defending blacks deprived of due process and other rights of citizenship. Oftentimes, he appealed cases to the Supreme Court and won; he understood the difference between federal and regional justice in America. Discrimination-weary blacks across the South spread the advocate’s legend. “Thurgood’s coming,” they hoped, when the legal system failed them.

His legal schedule hurt his health and his marriage. Smoking probably aggravated the stress of his gargantuan caseload. “I was on the verge of a nervous breakdown for a long time, but I never quite made the grade,” he once said.

Devil in the Grove is a milestone in Florida historiography. Through the context of the case, the author reveals the KKK’s lead role in spreading terror statewide since the Civil War. From 1882 to 1930, more lynchings of blacks occurred in Florida than in any other state—266. During the Great Depression, Klan membership in Florida remained strong at about 30,000. Anti-black violence peaked after World War II. In Tallahassee, Bill Hendrix appointed himself head of the newly chartered Southern Knights of the KKK. Orange County Sheriff Dave Starr, who served from 1949 to 1971, identified as a Klansman.

The year 1951 delivered what the Northern press called “The Florida Terror.” A dozen bombings and many attempted bombings struck black homes, synagogues, and Catholic churches. In November, the Klan dynamited Orlando’s Creamette Frozen Custard Stand for serving all customers at the same window, no matter their race. That Christmas, Florida NAACP leader Harry T. Moore and his wife Harriette were killed at their home by a bomb under their bed. The Saturday Evening Post called 1951 “the worst year of minority outrages in the history of Florida or probably any other state in recent times.”

The Groveland case is a prism for understanding themes in national civil rights history. It is emblematic of the violence and intimidation suffered by homecoming black veterans at the hands of white oppressors.

Two of the defendants, Samuel Shepherd and Walter Irvin, served in World War II and wore their uniforms around their home neighborhoods upon their return. It is probable that their military status worsened their experience in the criminal justice system; KKK members and sympathizers in Florida found great cause for attacks against black servicemen. They resented their advanced station. “Fathers of black soldiers warned their sons not to come home in their uniforms because police had made a practice of searching and beating black military men,” King reports in Devil in the Grove.

In 1946 rural Georgia, a white mob killed George Dorsey, a World War II veteran, as well as his wife and another couple in the car. In Columbia, Tennessee, that same year, a race riot ignited when Navy veteran James Stephenson got into a fistfight with a white shop clerk. Also in 1946, recently honorably discharged World War II veteran Isaac Woodard, still in uniform, was beaten by police in Batesburg, South Carolina for a verbal dispute with a white bus driver. The battery blinded him for life.

Devil in the Grove evidences the Groveland case’s considerable role in shaping Marshall’s mindset as a Supreme Court advocate and justice. The case is essential to understanding how and why Marshall successfully argued for his plaintiffs in Brown v. Board of Education.

Analysis of King’s book would improve national civil rights dialogue on Black History Month or any month. Devil in the Grove deserves a place of prestige in American history curriculum. It could serve as a modern companion to Solomon Northup’s memoir, 12 Years A Slave.