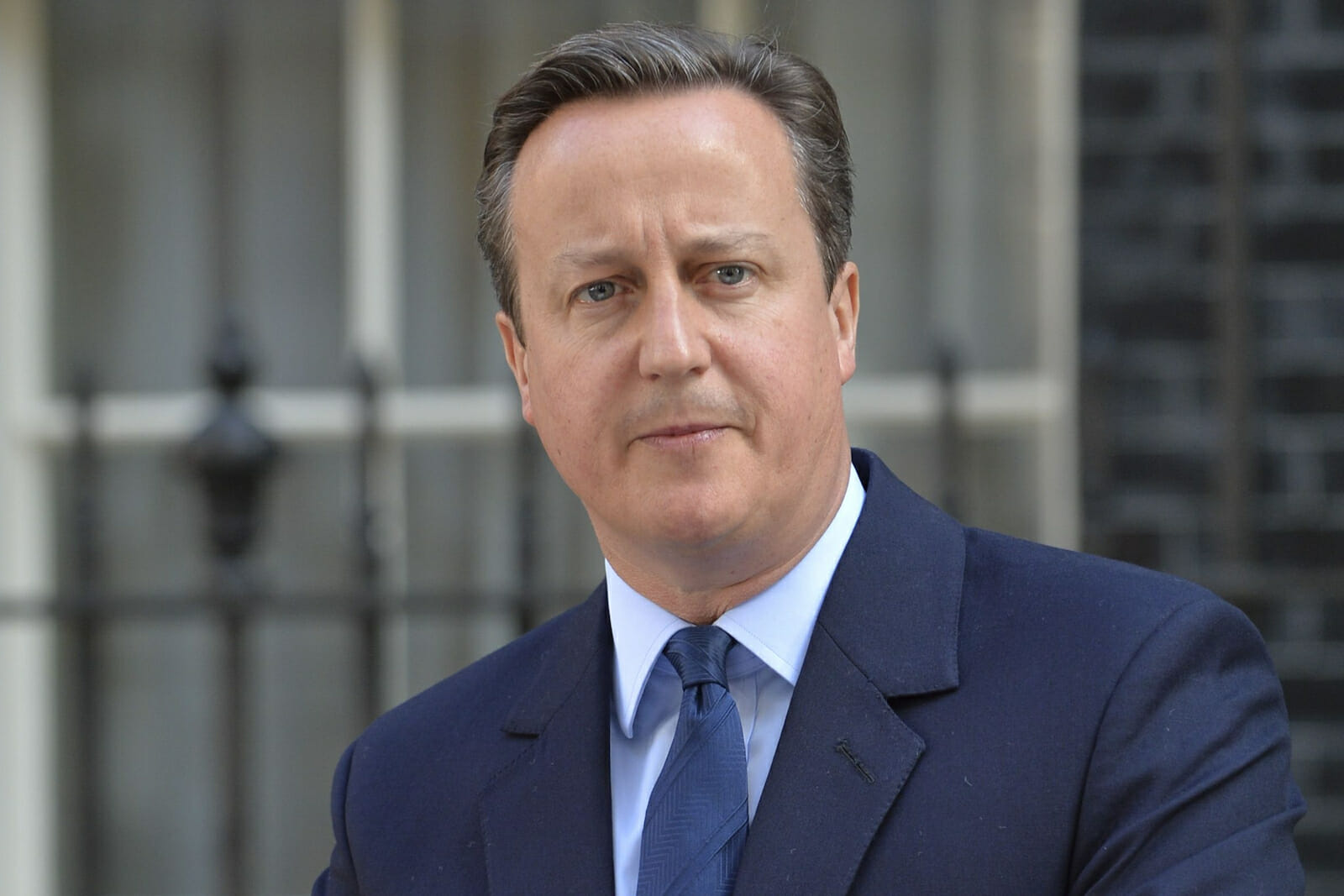

British Defence Policy under David Cameron

The SDSR, “Securing Britain in an Age of Uncertainty: The Strategic Defence and Security Review,” was released by the David Cameron government in October of 2010. Despite calls for deep cuts to the military budget, British defence policy under David Cameron mirrors the policy directions taken by his predecessors, Gordon Brown and Tony Blair.

For example, the UK will continue to have an operational military presence in Afghanistan and the Balkans and a non-operational presence in Cyprus, the Falkland Islands, Gibraltar, Germany, and Northern Ireland. The parliamentary elections last year were essentially a mandate on Labour’s handling of the economy. The general campaign theme of the Conservative Party was the UK’s dire economic circumstances and the need for difficult spending cuts to confront the UK’s massive debt burden and return the UK to fiscal solvency. As leader of the Conservative Party David Cameron posted on his WebCameron blog at the beginning of 2010, “I defy anyone to look at our plans and call them timid – because the truth is they cannot be timid if we’re to confront and defeat these problems.”

The cuts proposed by David Cameron, reflect his pragmatic approach and his acknowledgment that in order for the UK to stay competitive and respond to threats from external and internal actors, defence spending had to be addressed in a responsible manner. Britain’s Treasury establishes the fiscal problems facing the UK, “Last year, the Government borrowed one pound in every four that it spent, and the interest payments on the nation’s public debt each year are more than the Government spends on schools in England.” Further, the UK owes £43 billion in interest on its debt.

In a speech given in 2010 at the beginning of the campaign, David Cameron laid out his arguments as to why further Labour Party rule would be fundamentally devastating for the UK and its economy. In the speech, which very well could have been given by Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI), Cameron said, “The next general election is no more than 153 days away and I don’t think it can come soon enough…Britain needs responsible economic policies that deal with our debts, so we have stability to create jobs and keep mortgage rates and taxes lower.” Cameron continued, “Since I started speaking today, more than half a million pounds has been added to our national debt.”

George Osborne told a conference before the election, while he served as the Shadow Chancellor “Our country stands at one of those forks we come across as we travel the roads of our history…Britain can either continue down a path of decline and fall, a path with rising debts, higher mortgage rates, ever-rising taxes, and high unemployment…That is Labour’s path. It always has been. We know where it leads and we must never allow this country to be dragged there once again.”

David Cameron argued in the House of Commons in October of 2010 that the cuts to Britain’s defence forces would allow for the UK to be more readily prepared to address many global challenges. In his remarks, Cameron suggested that the UK military must be “more thoughtful, more strategic and more coordinated in the way we advance our interests and protect our national security.”

Besides cuts to defence the UK witnessed the worst urban unrest in years as cuts to domestic programs like education and the NHS were announced separate from the defence cuts. Among the education cuts are £215 million to teaching budgets. The effort by the Cameron government to curtail defence spending is a reaction to increased defence spending by Tony Blair. Cameron has called for cuts to defence spending by 8% over the next four years. To accomplish this goal, 25,000 civilians at the Ministry of Defence will be let go and the RAF and Navy will each face 5,000-job cuts. The Army is expected to lose about 7,000 personnel and achieve a force level of about 95,500. Cameron announced that the HMS Ark Royal, an Invincible-class light aircraft carrier would be decommissioned. Two additional aircraft carriers previously approved will be built but one would be essentially mothballed until it is needed.

Additionally, the Harrier Jump Jets will be decommissioned and the Nimrod MRA4 reconnaissance planes will not be purchased as replacement vehicles.

As the SDSR takes great pains to point out the decision to purchase two aircraft carriers was made by the Brown government. “In terms of the Royal Navy, we will complete the construction of two large aircraft carriers. The Government believes it is right for the United Kingdom to retain, in the long term, the capability that only aircraft carriers can provide – the ability to deploy airpower from anywhere in the world, without the need for friendly air bases on land…But the last Government committed to carriers that would have been unable to work properly with our closest military allies.”

In the near term, British carriers will be fitted with catapults to enable the use of the flight decks for French and American F-35 Joint Strike Fighters. This action would accommodate their fighter planes and would compensate for a shortage of British fighter planes that is a direct result of the defence cuts. The paradox is that due to the cancellation of the Harrier jets the new aircraft carriers will be planeless for perhaps ten years. The Wall Street Journal points out, “The Harrier is to be scrapped in the defence cuts program. That means that, astonishingly, Britain will soon have two new aircraft carriers—both ordered by the last government in better times at a cost of £5.2 billion ($8.1 billion) —but no planes to fly from their decks for almost ten years…Aircraft carriers without aircraft counts as a proper mess. The prime minister was lucky not to be put under more pressure on this when he unveiled his cuts to the House of Commons.”

The situation in the UK mirrors the budget debates in the U.S. While the U.S. Congress debates significantly larger defence cuts both situations are a result of the current global economic slowdown and the increased defence spending by Tony Blair and George W. Bush, both of whom made significant increases in defence spending as a reaction to 9/11 and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. From 2000 to 2009 the U.S. increased its military expenditures by $335 billion dollars or 89% and the UK increased its expenditures by $15 billion or 28%. Not all of the increases can be attributed to Iraq and Afghanistan. The increases can also be attributed to the fact that as nations expand and grow in population there are increased expenditures in certain sectors. Along with this growth, competition and threats increase resulting in increased defence spending. Of the total share of military expenditures in 2009, the U.S. share was 46.5% and the UK’s was 3.8%.

Referencing the economic policies of the Blair and Brown years, the SDSR suggests, “The difficult legacy we have inherited has necessitated tough decisions to get our economy back on track. Our national security depends on our economic security and vice versa. So bringing the defence budget back to balance is a vital part of how we tackle the deficit and protect this country’s national security.” Other cost-saving measures illustrated by the SDSR will reduce from 12 to 8 the number of operational launch tubes on its nuclear submarine fleet, as well as a reduction from 48 to 40 the number of warheads. It is estimated that this will save roughly £750 million initially and £3.2 billion over a ten-year period. Despite these cuts in spending the essential point is that the UK’s foreign and defence policies follow a linear path. Foreign and defence policies do not differ significantly from government to government.

As stated in the Strategic Defence and Security Review, “five priorities for our international engagement” are established; the United Kingdom’s and America’s strategic partnership shall be a cornerstone to UK security, a reformed UN that’s responsive and effective, a powerful NATO, a European Union that’s able to promote security and prosperity for member states and those in Europe which are not full members and “new models of practical bilateral defence and security cooperation with a range of allies and partners.”

The defence cuts called for are modest compared to the cuts that Chancellor George Osborne had originally proposed. Over protests from Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Defense Secretary Robert Gates, Cameron is postponing the deepest cuts until the NATO mission in Afghanistan is scheduled to conclude. Both U.S. Secretaries expressed concern that the UK’s military capabilities would be hampered by any deep cuts. According to Clinton in an interview in Brussels if the cuts concerned her, “It does, and the reason it does is because I think we do have to have an alliance where there is a commitment to the common defence. Nato has been the most successful alliance for defensive purposes in the history of the world I guess, but it has to be maintained. Now, each country has to be able to make its appropriate contributions.”

According to Secretary Gates, when asked if he had similar reservations, “My worry is that the more our allies cut their capabilities, the more people will look to the United States to cover whatever gaps are created.” Gates continued, “At a time when we are facing stringencies of our own, that’s a concern for me.” The cuts have also brought the country’s military leaders to No.10 Downing Street to voice their concerns. Among them were the First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff, Admiral Sir Mark Stanhope, the Chief of the Air Staff and head of the RAF, Air Chief Marshal Sir Stephen Dalton, and Chief of the General Staff, General Sir Peter Wall. Defence Secretary Liam Fox also publicly voiced his opposition to drastic cuts to any and all of the military branches.

In the realm of foreign affairs, the Conservative Party’s many core assumptions resemble those of liberalism and of previous governments. Among the stated positions of the Conservative Party; “A Conservative Government will champion a distinctive British foreign policy, based on the renewing and reinforcing of our engagement with the rest of the world, the promotion of free trade, the tackling of climate change and poverty and the upholding of our values. Our approach to foreign affairs is based on a belief in freedom, human rights, and democracy.”

In 2006, while still an MP, David Cameron laid out several policy positions in a speech to a Conservative Party conference. Cameron made a distinction and offered clarity concerning the assumption that some hold that he is a neo-conservative. David Cameron considers himself a liberal-conservative, “I’m not a neo-conservative. I’m a liberal Conservative. Liberal – because I believe in spreading freedom and democracy, and supporting humanitarian intervention.” In neo-conservative thought, the pursuit of humanitarian intervention, freedom, and democracy only occur if there is a national interest, and rarely are dealt with until there is a national imperative.

Similarly, in a speech in Islamabad, Cameron suggested, “We should accept that we cannot impose democracy at the barrel of a gun; that we cannot drop democracy from 10,000 feet – and we shouldn’t try.” Cameron continued, “Put crudely, that was what was wrong with the ‘neo-con’ approach, and why I am a liberal Conservative, not a neo Conservative…I believe we should work patiently and steadfastly to advance liberal values wherever we can to build the characteristics of an open society wherever we can confident that in time, democracy will result.”

Currently, the only mission abroad where the UK has a significant troop presence is in Afghanistan. Cameron clearly must balance the fact that the war is increasingly unpopular at home while keeping the commitments made by his predecessors to stay the course. In a speech at the 2009 Conservative Party conference in Manchester, David Cameron was emphatic on two points, “If we win the election the first and gravest responsibility I will face is for our troops in Afghanistan and their families at home…We need a strategy that is credible, and do-able. We are not in Afghanistan to deliver the perfect society. We are there to stop the re-establishment of terrorist training camps.”

Therein lies the dilemma for NATO, the U.S. and now David Cameron’s government. Afghanistan is a long-term commitment. Britain’s commitments in Afghanistan are predicated on Britain’s membership in NATO and their transatlantic partnership with the United States. This relationship is unique and historic and despite some setbacks in the past, this partnership will continue under the leadership of David Cameron and future Prime Ministers. The Conservative Party points out, “We regard our defence relationship with the United States as particularly important. We will also continue to seek good inter-governmental relationships with our European neighbours on defence procurement.”

Because the British remains a committed partner in NATO, it is committed to the NATO mission in Afghanistan. The British could withdraw from Afghanistan but not without suffering severe condemnation from its fellow NATO and American partners. The NATO/UK partnership is reciprocal in nature. The Conservative Party argues, “We want to maintain good defence relationships with our European neighbours. However, we believe that NATO, whilst in need of reform, should remain the cornerstone of our defence.”

The SDSR illustrates that despite the budget cuts any commitments to NATO will remain in place. Specifically, “The UK is a founding member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), which has been the bedrock of our defence for over 60 years. Our obligations to our NATO Allies will continue to be among our highest priorities and we will continue to contribute to NATO’s operations and its Command and Force Structures, to ensure that the Alliance is able to deliver a robust and credible response to existing and new security challenges.” Cameron stressed in his House of Commons speech that his government would meet the NATO requirement that member states continue to spend 2% of their GDPs on their militaries.

While the UK is mired in a severe economic recession and its foreign policy is squarely focused on Afghanistan there will be no significant shift from its current strategic commitments in Afghanistan. Before Tony Blair left office he began removing all British combat troops from Southern Iraq. Gordon Brown subsequently completed this policy. This has allowed subsequent governments significant latitude regarding the projection of its forces abroad.

Cameron’s first foray abroad was not to the United States but to continental Europe where he met with his counterparts in France and Germany. In order to reassure the Americans that he was committed to the transatlantic partnership, he sent his Foreign Secretary William Hague to the United States to meet with Secretary Clinton. Cameron told reporters in France in reaction to a question regarding closer integration with the Eurozone countries in light of the Greek and Portuguese debt crises, “I think we were right to stay out of the euro…But let me be absolutely clear: it’s in Britain’s interest that the eurozone is a success.”

Cameron would prefer to remove British troops from Afghanistan and gain support from the British electorate. This option, however appealing, is not a realistic one. The UK is committed to Afghanistan for the foreseeable future as it was under the Blair and Brown governments. Prime Minister Cameron faces difficult domestic and foreign policy choices. Acknowledging that asymmetric threats like cyberattacks pose new challenges, the Cameron government is increasing funding by £650 million over a four-year period to the National Cyber Security Programme. The SDSR specifically points out that there is a gap between the current capabilities of the government and the rapidly changing threat environment brought about by advances in technologies.

Along with the SDSR, the government also released the National Security Strategy and the Spending Review 2010. Both the NSS and the SDSR essentially lay out a strategy in the areas of resources, capabilities, and national security. The Spending Review sets the budgets for each department in the Government until 2014-2015. Taken together all three illustrate a myriad of problems facing the UK. Although the defence cuts planned by Cameron are a departure from Labour, his policies are a continuation of Brown’s.

When candidates run for high office whether Senator Obama or David Cameron they attempt to paint the opposing party in power as ineffectual. Then-Senator Obama portrayed a Bush White House whose anti-terrorism policies were wrong for America and needed to be updated. When Obama won the White House he continued many of the same Bush administration policies as they relate to Afghanistan.

Despite signing an Executive Order, he has failed to close Guantanamo Bay. Additionally, Obama has killed more would-be suicide bombers in the mountains between Afghanistan and Pakistan through the use of drone missile attacks than did the Bush administration. Cameron has had to straddle several competing interests regarding Afghanistan. The war is exceedingly unpopular at home but he is committed to the NATO mission until at least 2015.

Cameron has also come under fire for publicly supporting the democratic aspirations of the protesters in Egypt while at the same time visiting the country recently with several British arms dealers in tow. This comes to light even as we are reminded of the Prime Ministers’ criticisms of Scottish Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill’s decision to release Libyan Abdel Basset Ali al-Megrahi. With the recent unrest in Libya where hundreds have been killed the Daily Mail is reporting, “arms sales to Libya have continued. Since the General Election, Britain has sold crowd control ammunition, sniper rifles, and tear gas to Tripoli.”