Books

Can China Create a World in its Own Image?

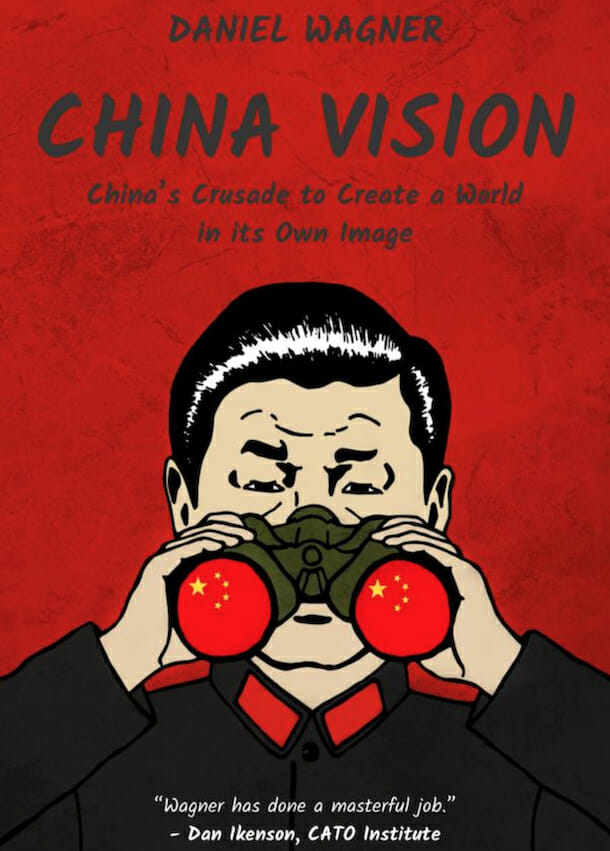

In the wake of Chinese leader Xi Xinping’s moves to make himself ruler for life, everyone is wondering about his government’s ambitions for its role in the world. Daniel Wagner has written about what the trends indicate in China Vision: China’s Crusade to Create A World in its Own Image.

The book notes the paradox that China is in regards to investment. The world’s 2nd largest economy continues to accept billions of dollars in development loans from banks like the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. Meanwhile, Chinese state banks are loaning trillions of dollars to countries around the world. Chinese entrepreneurs are feverishly setting up businesses abroad and purchasing foreign companies and real estate. If a foreigner wants to invest in China though, they must accept ownership stake limitations and obey rules that explicitly make them less competitive. In regards to domestic investment, Wagner argues that China invests way too much on grand public projects, like apartment blocs that remain largely vacant, and not enough on small-midsized businesses. One of these days (the next global recession?), the chickens will come home to roost and China will have to re-evaluate its blank-check policy.

Much of the book focuses on China’s role in foreign diplomacy and commerce. The fledgling superpower is in the process of spending trillions of dollars on loans to the developing world, particularly through its Asia-oriented Belt and Road Initiative. These no-strings-attached loans give China enormous power over many of the poorest countries in the world. Many people, like former Maldivian PM Mohamed Nasheed, have outright accused China of imperialist behavior. The author writes that “Kenya was to be forced to relinquish control of its largest and most lucrative port in Mombasa to Chinese control as a result of Nairobi’s inability to repay its debts to Beijing.” China also owns ports in locales as diverse as Djibouti City and Zeebrugge, Belgium. Chinese firms are likewise emulating some neo-colonial tendencies. For instance, Wagner writes that “Fewer than half of these [African-based Chinese] firms sourced inputs or had African management.” Controversial Chinese real estate projects like Forest City, Malaysia are, arguably, examples of literal colonialism.

Through this strategy of buying friends and building a global network of ports, China is strengthening its impunity as a Top 3 naval power. Increasingly, China is treating the South China Sea as its private fiefdom by ignoring credible territorial claims of the Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoal by the Philippines, Indonesia, Japan, Brunei, Malaysia, and Vietnam. Most disturbing of all is Xi’s recent verbal aggression towards Taiwan. By buying friends, China can mute criticisms of this military aggression in the UN and isolate foes like Taiwan (only 19 countries have diplomatic relations with it). With a rapidly expanding fleet of sea craft, the People’s Liberation Army Navy is better equipped than ever to project hard power via all of China’s ports, from off the coast of the Philippines to Belgium. On this dire note, I wish Wagner had written more about the budding conflict between China and the other 1B-person country in the world, India. I predict that the dichotomy between democratic India and totalitarian China will determine the future of humanity. Seeing as India and China (and China’s close ally Pakistan) all possess nuclear weapons and have recent military skirmishes with each other, one can only hope that the Tiger and Dragon don’t initiate WWIII squabbling over a sleepy locale like Kashmir or Nepal.

In the final section of the book, Wagner writes about China’s dominance in the virtual sphere. Chinese tech companies like Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent are rapidly catching up and even beating Silicon Valley in terms of traffic, profitability and innovation (most importantly, AI). China has also become the de facto global leader in green technology. China’s blank-check philosophy funds these rapid advancements. A lot of this apparent innovation, however, is fuelled by corporate espionage. For the past few decades, Chinese firms (often with official backing) have been using spies and hacking to steal blueprints and thus reverse engineer inventions. Ironically, these knock-offs are oftentimes sold to the US government, which creates a huge security risk. In many cases, Western companies willingly share confidential data with China in order to be granted access to the Chinese market.

China’s running racket of stealing IP and personal user data from US companies that choose to operate in China demonstrates the importance of government regulation. In this case regarding national security and user privacy protection. Ironically, China enforces data encryption and other cybersecurity measures through regulations like the 2017 Cybersecurity Law. The willingness of Western companies to literally sell themselves out to China in the frenzied hope of making a quick buck in the world’s largest market is textbook junkie-mentality. These free market free-basers expose their fundamental flaw in the face of China’s system of state capitalism. By ceding responsibility of investment from the government to the private sector solely, countries like the US are being vastly outspent by China in everything from space travel to quantum computing research. As economists like Michel Aglietta and upstart politicians like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez point out, the state must be responsible for picking up the slack when the free market fails to focus on important long term projects, like a Green New Deal (China already has its own publically funded version of the GND).

China Vision is a good account of the Chinese Communist Party’s domestic heavy-handedness and foreign diplomacy-via-blank-check. The two are interconnected, as China’s crackdown on internal dissidents informs how it treats foreign countries and human rights activists who dare to oppose it. Through China’s Belt and Road Initiative of loaning billions of infrastructure dollars to developing nations, it can control them through a carrot-and-stick approach. China’s spy state apparatus is also being used to sabotage foreign humanitarian organizations, religious groups, governments, and companies. The CCP may soon export its surveillance state blueprint to other interested authoritarian states, setting the stage for a cold war between China and its client dictatorships and Western democracies. The People’s Liberation Army is preparing for this possibility with a huge naval buildup in the contested South China Sea, aided by all of the “civilian” ports that it’s building there under the auspices of the BRI. Daniel Wagner’s book does a good job of explaining these geopolitical trends in a concise and even-handed way. He explains how colonialism and the Cold War helped to shape China’s cynical outlook on the world and doesn’t exaggerate China’s capabilities. Anyone in politics, tech, economics or the NGO sphere will learn a lot from this book.