China, The Frog and the Scorpion

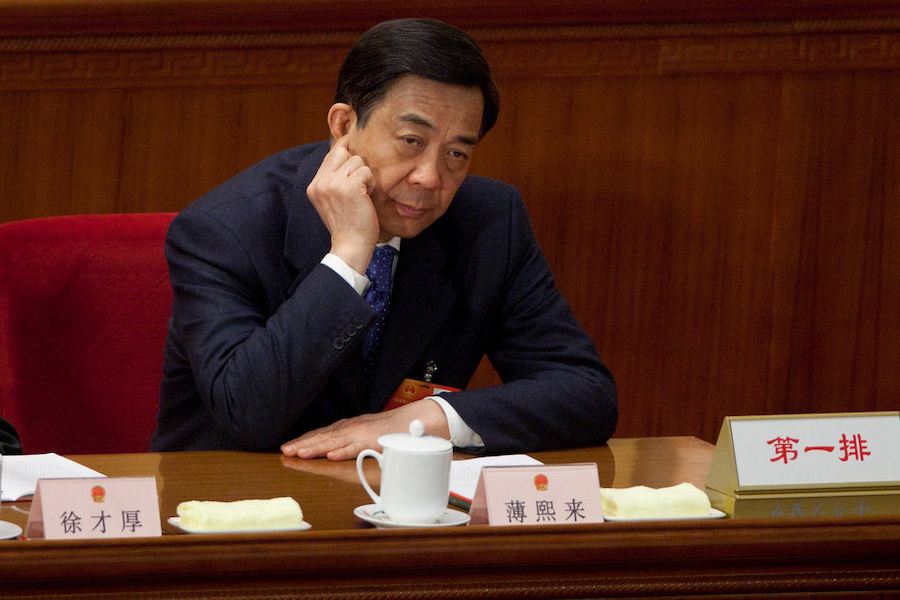

Behind the political crisis that saw the recent fall of powerful Communist Party leader, Bo Xilai, is an internal battle over how to handle China’s slowing economy and growing income disparity, while shifting from a cheap labor export-driven model to one built around internal consumption. Since China is the second largest economy on the planet—and likely to become the first in the next 20 to 30 years—getting it wrong could have serious consequences, from Beijing to Brasilia, and from Washington to Mumbai.

China’s current major economic challenges include a dangerous housing bubble, indebted local governments, and a widening wealth gap, problems replicated in most of the major economies in the world. Worldwide capitalism—despite China’s self-description as “socialism with Chinese characteristics”—is in the most severe crisis since the great crash of the 1930s. The question is: can any country make a system with serious built-in flaws function for all its people? While capitalism was the first economic system to effectively harness the productive capacity of humanity, it is also characterized by periodic crises, vast inequities, and a self-destructive profit motive that lays waste to everything from culture to the environment.

Can capitalism be made to work without smashing up the landscape? China has already made enormous strides in using its version of the system to lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty and create the most dynamic economy on the planet, no small accomplishment in an enormous country with more than a billion people. Over the past 30 years, China has gone from a poor, largely rural nation, to an economic juggernaut that has tripled urban income and increased life expectancy by six years.

But trying to make a system like capitalism work for all is a little like playing whack-a-mole. For instance, China’s overbuilding has produced tens of millions of empty apartments. “If we blindly develop the housing market [a] bubble will emerge in the sector. When it bursts more than just the housing market will be affected, it will weigh on the Chinese economy,” said China’s Premier, Wen Jiabao. And, indeed, by controlling the banks—and thus credit and financing—real estate prices have recently fallen in most mainland cities.

But since 13 percent of China’s Gross Domestic Product is residential construction, a sharp drop in building will produce unemployment at the very time that a new five-year plan (2011-2015) projects downshifting the economy from a 9 percent growth rate to 7.5 percent.

What worries China’s leaders is that one of capitalism’s engines of self-destruction—economic injustice and inequality—is increasing. According to Li Shu, an economist at Beijing Normal University, from 1988 to 2007, the average income of the top 12 percent went from 10 times the bottom 10 percent, to 23 times the bottom 10 percent. According to the Financial Times, it is estimated that China’s richest 1 percent control 40 to 60 percent of total household wealth. Wealth disparity and economic injustice have fueled “incidents,” ranging from industrial strikes to riots by farmers over inadequate compensation for confiscated land. Endemic local corruption feeds much of the anger.

The government is trying to address this issue by raising taxes on the wealthy, lowering them on the poor, and including more “poor” in a category that makes them eligible for subsidies. Wen said last year that China aims to “basically eradicate poverty by 2020.” According to the United Nations, some 245 million Chinese still live in extreme poverty.

Beijing has also reined in the sale of land by local municipalities. But since the major way that cities and provinces generate money is through land sales, this has made it difficult for local areas to pay off their debts, maintain their infrastructures, and provide services. Whack one mole up pops another.

There is a growing willingness by the average Chinese citizen to confront problems like pollution, corruption, and even nuclear power. Part of the current debate in the Communist Party leadership is over how to respond to such increased political activity. Bo had a reputation as a “populist” and campaigned against economic injustice and corruption. But he was also opposed to revisiting the issue of Tiananmen Square, where in 1989 the People’s Liberation Army fired on demonstrators. Tiananmen has considerable relevance in the current situation since the main demands of the demonstrators were not democracy but an end to corruption and high food prices. It is no accident that, when food prices began rising two years ago, the government moved to cut inflation from 6.5 percent to 3.2 percent this past February.

While the government generally responds to demonstrations with crackdowns, that policy has somewhat moderated over the past year. When farmers ran local leaders and Communist Party officials out of the town of Wutan, the provincial government sent in negotiators, not the police. Anti-pollution protests forced authorities to shut down several factories. At the same time, the government has tightened its grip on the Internet, still arrests people at will, and is not shy about resorting to force.

It is clear the possibility of major political upheaval worries the current leadership and explains why Premier Wen recently called up the furies of the past. The current economic growth is “unbalanced and unsustainable” he said. “Without successful political structural reform, it is impossible for us to fully institute economic structural reform and the gain we made in this area may be lost,” and said that “such a historical tragedy as the Cultural Revolution may happen again.”

Changing course in a country like China is akin to turning an aircraft carrier: start a long time in advance and give yourself plenty of sea room. If China is to shift its economy in the direction of its potentially huge home market, it will have to improve the lives of its citizens. Wages have gone up between 15 and 20 percent over the past two years and are scheduled to rise another 15 percent. But social services will also have to be improved. Health care, once free, has become a major burden for many Chinese, a problem the government will have to address.

There are some in the Chinese government whose definition of “reform” is ending government involvement in the economy and shifting to a wide-open free market system. It is not clear that the bulk of China’s people would support such a move. All they have to do is look around them to see the wreckage such an economic model inflicts in other parts of the world. Can capitalism work without all the collateral damage? Karl Marx, the system’s great critic, though it could not. Can China figure out a way to overcome’s system’s flaws, or is this the tale of the frog and the scorpion?

The scorpion asked the frog to ferry it across a river, but the frog feared the scorpion would sting him. The scorpion protested: “If I sting you, than I die as well.” So the frog put the scorpion on his back and began to swim. When he reached mid-stream, the scorpion stung him. The dying frog asked “Why?” and the scorpion replied, “Because it is my nature.” Can China swim the scorpion across the river and avoid the sting? Stay tuned.