Compton Commodified: N.W.A. was Always a Blend of Fiction and Reality

Last week, Dr. Dre released Compton: The Soundtrack – his first album in 16 years – with cover art that features the iconic Hollywood sign transformed to read C-O-M-P-T-O-N.

The timing, title and cover imagery of the album coincide with the new biopic Straight Outta Compton, a film that details the rise and fall of Dr. Dre’s former rap group NWA (Niggaz Wit Attitudes), which, along with Dre, included Eazy-E, MC Ren, DJ Yella and Ice Cube.

NWA was active for only a few years, but their 1988 album Straight Outta Compton gave birth to West Coast gangsta rap – the controversial genre of music defined by its gritty depictions of inner-city street life.

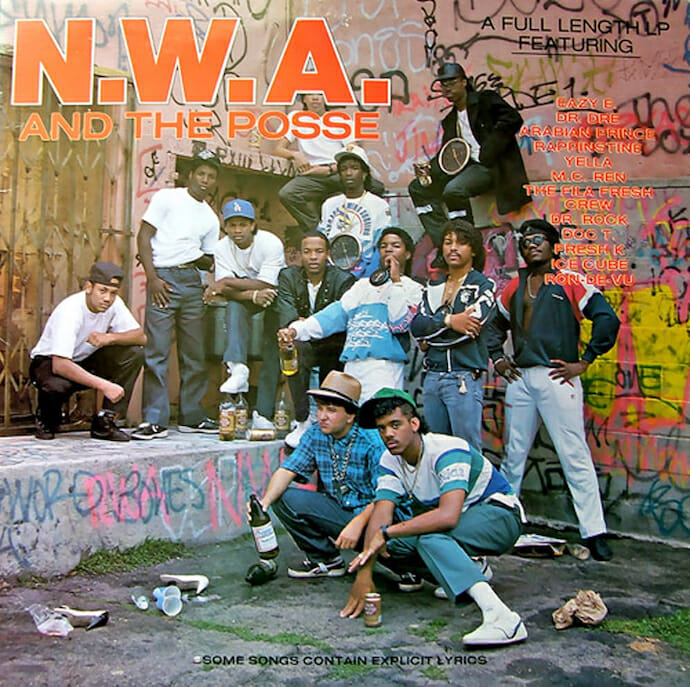

In NWA’s world, however, Compton and Hollywood have never been far apart. In fact, the photograph for the cover of the group’s first album – 1987’s NWA and the Posse – wasn’t even taken in Compton. Instead, it was shot in a graffiti-filled Hollywood alleyway near the group’s first record label.

And in a deeper sense, NWA’s brand of rap music was always a cinematic blend of reality and fiction: a blaxploitation film with beats. The genius of the group’s approach – masterminded by member Eric “Eazy-E” Wright – was the way it manufactured a narrative of Compton as a rough, unpredictable place, while placing it at the center of NWA’s identity.

Selling the hood

For decades, real estate boosters have packaged the Southern California good life, using images of sunshine and palm trees to entice millions of Americans to relocate to the West Coast.

Under the guidance of Eazy-E, NWA commodified a more sinister version of the Los Angeles story, crafting a new brand of hardcore rap that moved from third-person descriptions of street life to first-person portrayals of the gangstas themselves.

Compare earlier recordings like Eazy-E’s “Boyz-n-the-Hood” – which describes the arrest, trial and failed escape of a fictional drug dealer named Kilo-G – to NWA’s “Gangsta Gangsta,” in which Ice Cube actually assumes the role of an unrepentant criminal, proclaiming: “Taking a life or two, that’s what the hell I do/You don’t like how I’m living? Well, fuck you!”

Over Dr. Dre’s booming beats and sampled sounds of automatic gunfire, Ice Cube, MC Ren and Eazy-E rapped about their sexual prowess and penchant for violence. Playing upon stereotypes dating back to blackface minstrelsy, they tapped into a centuries-old American appetite for racialized entertainment.

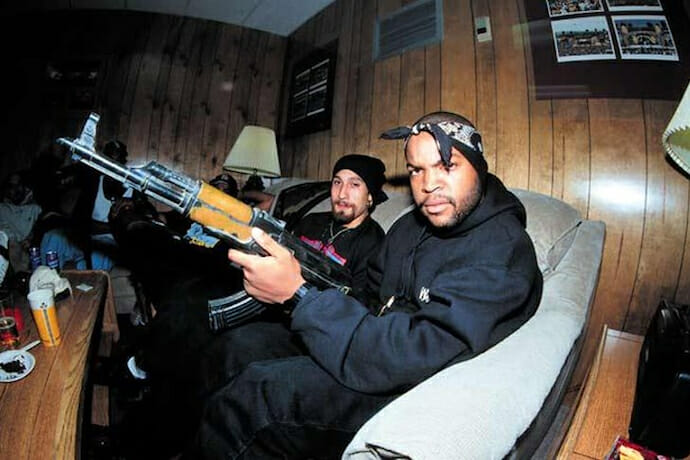

Meanwhile, in interviews, the group members were cagey. Understanding intuitively that their infamy was tied to record sales, they posed for pictures holding guns and refused to state clearly whether they were gang members, drug dealers or just kids looking to make a quick buck.

In truth, the only rap sheets NWA members had were notebooks full of song lyrics.

Although the group often claimed they were simply “street reporters,” the violent gang- and drug-filled world of their music ignored more prosaic aspects of Compton, such as its single-family homes and history as a black, middle-class enclave.

But in segregated Los Angeles, whites often avoided predominantly black communities and viewed black youth suspiciously. Straight Outta Compton played to their shrill, pervasive fears about gang violence, offering outsiders a vicarious look into a neighborhood most had only heard about on the nightly news.

Music fans ate it up: the album went double platinum and encouraged music industry executives to focus on developing more hardcore acts.

An underlying social message

Nonetheless, the larger-than-life personas populating NWA’s recordings spoke to complicated realities.

On tracks like “Gangsta Gangsta” Ice Cube might have sounded invincible – “I’m the type of nigga that’s built to last / Fuck with me, I’ll put my foot in your ass” – but all of that bravado masked real social insecurity.

NWA’s core members grew up in Compton and South Central neighborhoods that had been devastated by massive deindustrialization. The resulting poverty and unemployment proved fertile ground for the influx of cocaine in the early 1980s. They witnessed the dramatic rise in gang violence connected to it and felt the LAPD’s heavy-handed response.

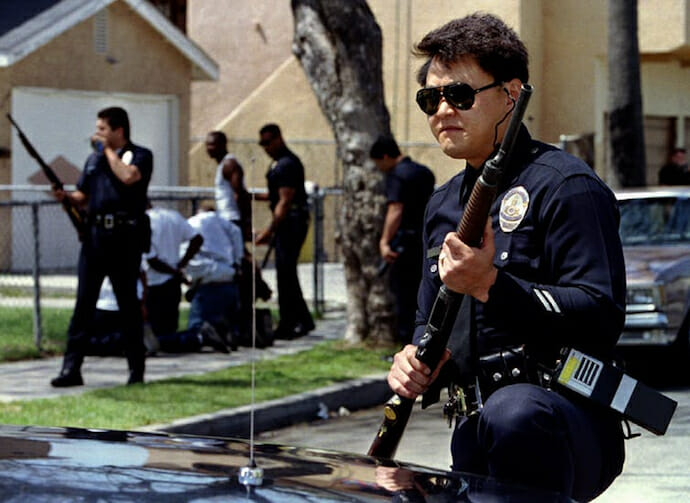

With draconian names like C.R.A.S.H. (Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums) and Operation Hammer, the LAPD criminalized entire neighborhoods, conducting destructive search and seizure missions with the dual purpose of finding contraband and intimidating residents.

By embracing the role of the “bad guys,” NWA found a profitable way to capture public attention and strike back at the system – a musical strategy I explore in my recent book Sounding Race in Rap Songs.

For example, in the video for “Straight Outta Compton,” the group members rap lyrics about their indomitable strength, but portray themselves at the mercy of one of the LAPD’s terrorizing gang sweeps. NWA’s critique, which came years before the Rodney King beating, provided fans with a glimpse at the LAPD’s worst practices under Police Chief Daryl Gates.

In the group’s most famous and controversial song “Fuck Tha Police,” they parodied courtroom proceedings. White police officers stood trial as defendants, Dr. Dre presided as judge, and rappers MC Ren, Eazy-E and Ice Cube served as prosecuting attorneys.

Testifying against the LAPD’s widespread racial profiling and excessive force, Ice Cube rapped: “Fuck the police coming straight from the underground/A young nigga got it bad ‘cause I’m brown/And not the other color so police think/They have the authority to kill a minority.”

A year after the police killing of Michael Brown and the ensuing protests, the timing the Straight Outta Compton biopic could not be better. #BlackLivesMatter and the Department of Justice report on Ferguson have helped shed light on ongoing patterns of police violence and harassment against black people nationwide.

Current events continue to make NWA look prophetic, and the biopic – along with Dr. Dre’s Compton: The Soundtrack – will certainly profit from them.

Whether that feels like a Hollywood cash in for the group or another attempt to say something meaningful remains a subject of much debate.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.