Elections in the Middle East

Do elections matter? It depends to some extent on the character of a polity. In democracies, they provide an opportunity for voters to pass judgment on their political leaders and whether or not they want them to continue in office. If they are unsatisfied, they can vote them out and replace them with a different set of political leaders. In more autocratic countries then, it would seem that elections do not serve the same purpose. Voters cannot remove the ruler or regime via the ballot box. So what is the reason for taking part?

Such questions are particularly relevant given the prominence of elections that have been taking place or are scheduled to happen in the Middle East. Israel and Syria have both held elections in recent months while Iran is scheduled to have a presidential election next week and Iraq early parliamentary elections in October.

Of the four, Israel and Iraq are judged to be the most democratic while Iran and Syria are autocratic. Using the Polity IV database which has a range from +10 (democracy) to -10 (autocracy), Israel and Iraq both have a net score of +6 while Iran is -7 and Syria -9. The scores are an aggregation of six different measurements that cover executive recruitment, constraints on government authority, and political competition.

Yet despite Israel and Iraq’s more democratic character, it is unclear if recent elections will lead to much change. Meanwhile, of the two more autocratic regimes, while Bashar al-Assad’s re-election was not unexpected, political change may well come about in Iran.

How then to account for the absence of change in more democratic countries like Israel and Iraq and the prospect of it happening in Iran? In short, context matters. In Israel, the election in March was the fourth in two years. The reason for the repeated elections is due in large part to the structure of the political system. Although Israeli politics and the public have become more right-wing and nationalistic over time, that sentiment has not been captured by one party who can command a majority in the Knesset but instead by a number of smaller parties. Those parties have had to negotiate with the larger parties to form governments. But because of the internal diversity and tensions within them, they have collapsed.

It may well be no different for Israel’s next government. A new coalition of eight parties was formed last week. Should it gain parliamentary approval it would be the first in 12 years not to have Benjamin Netanyahu at its head. But because the number of parties involved range from the centre to the right and include many politicians who distrust each other, it will be hard for them to agree on much.

Iraq’s challenge is different to Israel. There the connection between leaders and society has become weaker. Despite the presence of many political parties and electoral competition, many voters feel disconnected from the political process. The negotiations which take place to form governments after elections provide little space for the public while Iraq’s post-2003 governments have been perceived as distant and unrepresentative. That contributed to growing frustrations in society in relation to the lack of economic opportunities and income, poor public services, and growing public insecurity and disorder. This culminated in an outburst of protests during 2019 and 2020. As a result, when Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi came to power last year, he proposed to bring elections forward.

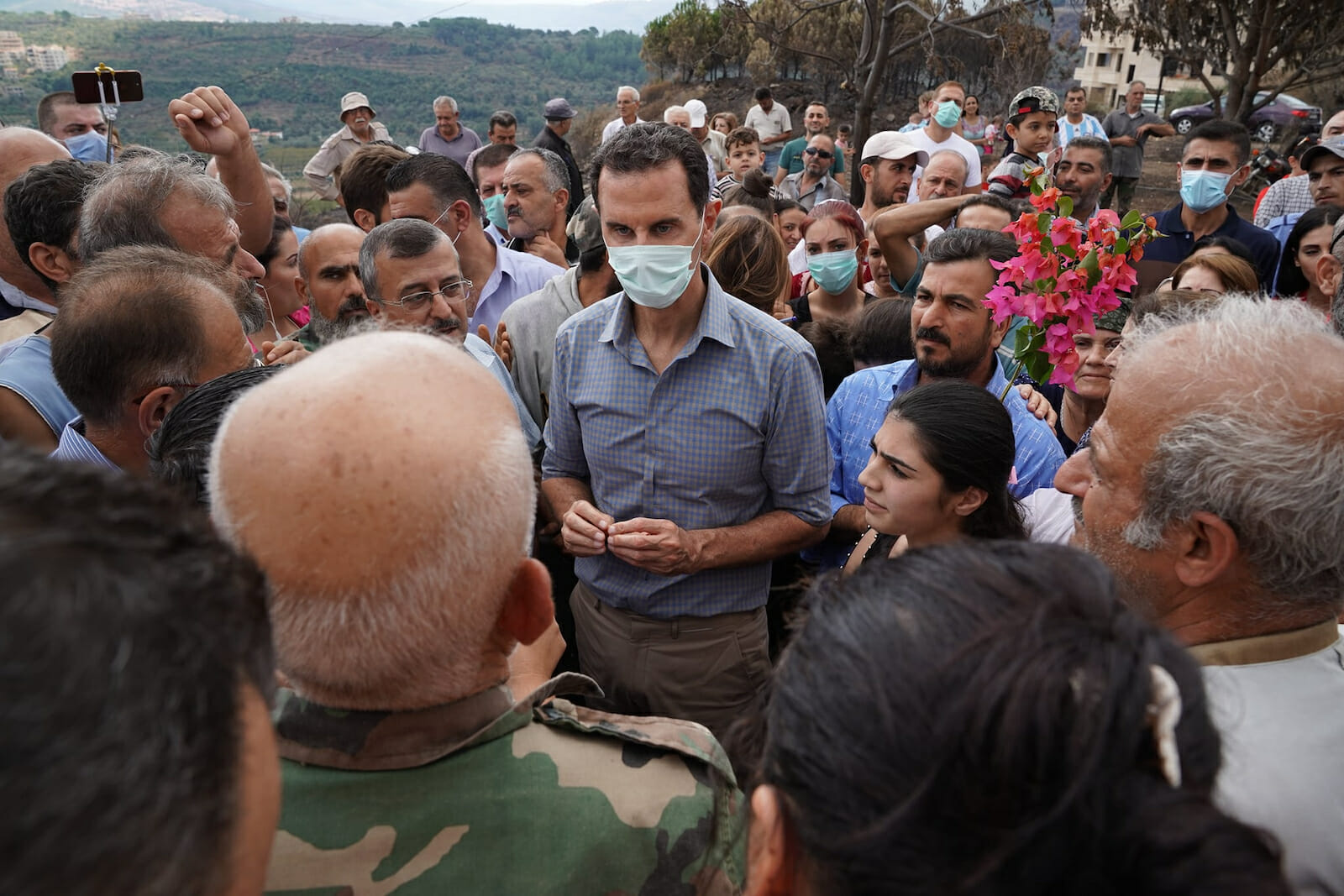

In Syria, President Bashar al-Assad won with 95 percent of the turnout in a poll that was rejected by the opposition and several Western countries for not being free or fair. Indeed, few expected Assad to lose the presidency which he effectively inherited from his father, Hafez al-Assad, in 2000 (and who himself held for 30 years before his death).

If Assad’s position was never in doubt, why then did he hold an election? A number of reasons may account for this. One is today’s political climate, which is dominated by the principle of democracy (i.e. rule by the people) even if its practice falls short. Therefore, even in autocracies, it is important for rulers to demonstrate their link to the people. Elections provide such a tool. Another is that Assad was keen to demonstrate his control over Syria, especially after 10 years of war and during which much of the country fell into the hands of his opponents and extremist groups like the Islamic State.

In contrast to Syria, Iran’s presidential election may lead to change – albeit in terms of personnel if not in substance. Although there are no political parties as such, there are two broad factions: the conservatives and the moderates. And after eight years of moderate rule by President Hassan Rouhani, a conservative is expected to win this year’s election.

The likelihood of a conservative victory was anticipated by the U.S. and helped drive its indirect talks with Tehran over its return to the nuclear deal. More recently, however, it seems likely that a form of resolution will be reached between the U.S. and Iran regardless of whether the new president is a conservative or moderate later this year.

Beyond foreign affairs, the influence of a conservative president could be felt domestically too. That might entail a more forceful stance in response to public protest and dissatisfaction at the deteriorating economy. Institutionally, a conservative president would also expand his faction’s influence over Iran’s various elected and unelected institutions, including parliament, the judiciary, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, and the oversight bodies like the Guardian Council. Such control could become important in determining the selection of a new Supreme Leader, should it become necessary.

Given the possibility of such change, why then is Iran considered to be non-democratic? Ultimately, it is down to the process that precedes elections, thereby limiting the choice for the voters. Last month the Guardian Council vetted all prospective candidates for the presidency. A key consideration in that process is whether or not a candidate is supportive of the regime. Those who are judged to be unreliable in that regard are excluded. In the end, only seven of the more than 500 prospective candidates were cleared to put themselves forward for the election. In addition, the Council’s selection was weighted in favour of the conservatives, with one or two representing the moderate faction.